|

Joker Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-House of Flying Daggers

-The Aviator

-Bad Education

|

|

Yun-Fat Recommends

|

|

-Eight Diagram Pole Fighter

-Los Muertos

-Tropical Malady

|

|

Allyn Recommends

|

|

-Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

-Songs from the Second Floor

|

|

Phyrephox Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-Design for Living (Lubitsch, 1933)

-War of the Worlds

-Howl's Moving Castle

|

|

Melisb Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-The Return

-Spirited Away

-Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter...And Spring

|

|

Wardpet Recommends

|

|

-Finding Nemo

-Man on the Train

-28 Days Later

|

|

Lorne Recommends

|

|

-21 Grams

-Cold Mountain

-Lost in Translation

|

|

Merlot Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-The Man on the Train

-Safe Conduct

-The Statement

|

|

Whitney Recommends

|

|

-Femme Fatale

-Gangs of New York

-Grand Illusion

|

|

Sydhe Recommends

|

|

-In America

-Looney Tunes: Back In Action

-Whale Rider

|

|

Copywright Recommends

|

Top 20 List

-Flowers of Shanghai

-Road to Perdition

-Topsy-Turvy

|

|

Stennie Recommends

|

Top 20 List

-A Matter of Life and Death

-Ossessione

-Sideways

|

|

Jeff Recommends

|

|

-Dial M for Murder

-The Game

-Star Wars Saga

|

|

Lady Wakasa Recommends

|

|

-Dracula: Page from a Virgin's Diary

-Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler

-The Last Laugh

|

|

Steve Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-Princess Raccoon

-Princess Raccoon

-Princess Raccoon

|

|

Jenny Recommends

|

|

-Mean Girls

-Super Size Me

-The Warriors

|

|

Lons Recommends

|

|

-Before Sunset

-The Incredibles

-Sideways

|

|

(c)2002 Design by Blogscapes.com

|

The Blog:

|

From the Archives: Donnie Darko

Well, in celebration of the fact that I’m going to see the Director’s Cut of Donnie Darko tomorrow afternoon, I’ve searched the archives for all links to our various postings on the film, an early Milk Plus favorite. Ah, lets go back to the halcyon days of 2002...

Post #1

Post #2

Post #3

Post #4

Post #5

Post #6

Post #7

Post #1

Post #2

Post #3

Post #4

Post #5

Post #6

Post #7

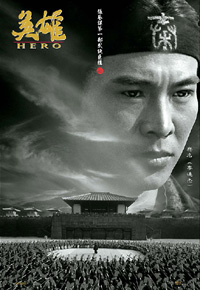

Hero

Well its finally here. I guess I could have watched the DVD version earlier (a lot earlier as it turned out) like phyrephox ( check out his earlier review), since its readily available just about everywhere, but Miramax actually decided to give Zhang Yimou’s film a theatrical release before it was able to reach the top of my Greencine queue. I’m going to leave the DVD of the HK version in my queue so I can see what, if anything, was changed in the Miramax-ed version (I’m going to assume that all the historical, English-language expository titles which bookended the film were added to the American release for an audience ignorant of Chinese history). Hopefully upon a second viewing, I will like the film a bit more.

Its not that Hero is a bad film, far, far from it, but with the combined talents of director Zhang Yimou, cinematographer Christopher Doyle, action director Ching Siu-tung, and stars Jet Li, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Maggie Cheung, Zhang Zhiyi, and Donnie Yen, well I guess I expected more emotional “oomph”. Hero owes a lot more to Wong Kar-wai’s art-house deconstruction of the wuxia pan genre, Ashes of Time, then it does to the international blockbuster Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon or the heritage cinema of Chen Kaige’s The Emperor and the Assassin (two of the more obvious points of comparison). But whereas Wong Kar-wai’s abstract narrative was just confusing, Yimou’s is plodding, composed mainly of a a back and forth, investigative conversation between Jet Li’s swordsman, referred throughout the film as “Nameless,” and the King of Qin, later First Emperor of China (Chen Dao-ming), as the two characters hash out the truth behind Nameless’s defeat of three renowned assassins from the neighboring kingdom of Zhao: Long Sky (Donnie Yen), Broken Sword (Tony Leung), and his lover Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung). Thus the bulk of the film is taken up with the retelling of the same basic series of events, a series of confrontations, duels, and subterfuge involving the four martial arts masters, as well as Broken Sword’s apprentice, Moon (Zhang Zhiyi). As Nameless relates his tale, the astute King of Qin becomes more and more skeptical of his patriotic warrior’s true motives, inevitably leading to tragic bloodshed and a healthy dosage of Chinese nationalism ( the final paragraph of J. Hoberman’s review nails the troubling ideological aspects of the film; given the historical nature of the Qin Dynasty, I tend to agree).

I actually think that Hero works better as an example of experimental cinema then it does as a work of narrative, which is how I came up with my comparison to Ashes of Time, and it is in this manner that the film derives a measure of poetry (more cynically, one could refer to Hero simply as a technical exercise). Zhang Yimou is obviously more concerned with the flutter of delicate, colored silk in the windswept deserts of Western China, for example, than he is with telling a classical narrative (which befits the abstract concerns of the narrative, since throughout the film, martial arts are compared to the ineffable arts of music and calligraphy). Befitting a collaboration between former cinematographer Zhang Yimou and ace DP Christopher Doyle, Hero is an extravaganza of color, light, and texture; no, make that a veritable orgy. Each major section of the film is dominated by a particular set of vivid hues, particularly expressed in the costumes (by Japanese designed Emi Wada), massive, symmetrical sets, and picturesque natural backdrops, all of which match the emotional register of the scenes: gray, black, and brown; red and gold; blue and green; white and black (and green again in a flashback), sometimes accentuated by digital effects, as if the filmmakers were actually painting on the screen (particularly noticeable during the red duel between Flying Snow and Moon).

Color may be one of Zhang Yimou’s top concerns, but it is not the only one. For one thing, movement throughout the film is aestheticized and abstracted, and we are not just talking about the wonders of wire-fu: the prevalent usage of slow-motion action; the usage of discontinuous editing which fractures space and disorientates the viewer, atomizing and capturing a single bit of movement, giving it emphasis, before moving on to the next instance (there are so many mismatches during the fight sequences that it could not just be simple sloppiness or lack of coverage); and frequent cutaways tracing the fall of a rain droplet, the radiation of ripples on a placid lake, or how fabric floats in the breeze.

Hero

Hero could also be characterized as a study of its actors faces. Tony Leung Chiu-wai has made an entire career out of contemplative looks, and his ability is again used to great effect (whereas Jet Li’s face is expressionless, masking the rage bubbling underneath; the beautiful faces of Maggie Cheung and Zhang Zhiyi are most often used by the filmmakers to convey passion and anger); probably the most common shot in the entire film is a close-up of an actor centered within the widescreen frame, held just long enough for the audience to absorb the actor’s features. The sound design is another facet of the film that I really enjoyed: the clatter of swords; the light splashes of water as Broken Sword and Nameless halfheartedly duel across the waters of a mountain lake; the whistle of thousands of arrows; the booming cry of the advancing Qin Army; echoing cries of anguish; the rustle of leaves; the vengeful entreaties of the eunuchs calling for execution in unison. Chilling, and I did even mention the use of music, by composer Tan Dun, which features Itzhak Perlman on violin, vocals by Faye Wong, and Kodo drumming.

You know, as I write about the film and reflect upon it more, I find that the sound and images continue to linger in my memory, which I usually consider an achievement in and of itself. Whatever faults the film may have narratively, it is an impressive technical achievement and beautiful to experience. Perhaps, I shall have to see the film again sooner than I expected.

The Brown Bunny

The girls dig Vincent Gallo, but Gallo doesn’t dig the girls. Or at least his character, Budd Clay, doesn’t dig the girls. In The Brown Bunny it is initially difficult to separate Gallo the man from Clay the character since the film-written, directed, produced, edited, shot, and partially scored by Gallo, among other things-is probably one of the most independent, and highly personal films to hit cinemas outside of a documentary circuit. Decidedly minimalist, The Brown Bunny opens with a fervor of activity in a sprightly photographed motorcycle race of which Clay is a (losing) participant. After the race Budd packs his bike into his van, fills up his tank with gas, and then does a curious thing. When he notices the gas station clerk’s name is Violet he pleads with her to come to California with him. Gallo’s fervent eyes, blazing out of his ruddy, unshaven cheeks exude a loser’s need, but he comes off understandably creepy. Still, the girls dig Gallo. Violet agrees to Budd's request and joins him in the van. Budd stops off at her house, and after a brief but intense kiss he lets her go retrieve her stuff from the house, and he leaves her there, taking off across the country to his next race in California.

What follows can best be described as an ambling but focused trip down U.S. highways and town streets. Much of the middle portion of the film is shot from the center console of Budd’s van, facing either out the front window watching the road approach or recording Budd’s face as he transverses the country. The film is simple to a T but poeticized through Gallo’s long takes, obvious aesthetic decisions and agreeable metaphors. Chief among the later are the three women he encounters on the road-really the only human contact and plot points in the film in the long stretch between New York State and California-who are all named after flowers, a trait shared by his Clay's dreamily remembered ex-girlfriend Daisy (Chloë Sevigny). In general his experience with each woman is like that between him and Violet. There is little verbal communication and what takes place feels less a true human connection and more an outburst of deeply emphatic physical need.

These connections are a test or compulsion of Budd, almost a pathological need to seek the kind of intimacy that he seems to have lost somewhere along his way. That loss, the deep isolation of the man, is only too clear in Gallo’s long, but never tedious, visual log of the road trip. Deeper still is the pain inside the character, and though Gallo probably could not be called a terrific actor, his use of limited dialog in the film is highly effective, for when he occasionally does speak it is in a whiney, vulnerable, quasi-effeminate voice that resonates with a bewildered loneliness which explains the reticent exterior.

Moments of transcendence are necessary in such a dismal, though beautiful, travelogue, and when they do come they hit like a ton of bricks. While much has been made about the explicitness and authenticity of Budd’s re-meeting and sexual engagement with Daisy when he finally reaches L.A., the moment is tainted with the same failure of intimacy and mutual cooperation as Budd’s experiences with other girls.

Instead, The Brown Bunny’s true exhilaration is halfway through the trip when Budd stops off at a salt flat to take out his bike. Riding off into the horizon, Gallo’s bike approaches and then passes the line where radiating heat waves meet the landscape. The bike proceeds to glide off on a surface that looks like a a rippling mirror, the bike was coasting on a shimmering reflection of itself. The moment exemplifies the ambiguity in Gallo’s minimalism. For one, the salt flat race is a relief for the audience because we are no longer watching Budd’s placid journey from his passenger seat and the same can probably be said for Budd himself, he is no longer following the repetitious, pathological pattern of his voyage. But at the same time all he really is doing is driving again; he may be going faster and approach a sense of freedom but the bike will always return to its dependency on the van and likewise Budd will eventually go looking for a solution to his inner hurt.

When Budd arrives in L.A.-which looks about as dreary as Vegas and the other few stopovers Clay makes through America-and finds his fantasy’d Daisy fawning over him just like the other girls it momentarily seems like Budd will transcend his loneliness, get past whatever it is he has issues with. By then the plot kicks in in overdrive, pounding the viewer with flashbacks digging up the root of Budd’s pathology. The revelation is neither a blessing nor a curse; Budd opens himself up to a terrible wound and Gallo uses enormously forceful and aesthetically controversial direction to stage the revelation in lieu of psychologically rich content. When it is all said and done Gallo refuses to determine Budd’s fate. After his encounter with Daisy Budd neither races nor picks up more girls, but self-realization does not necessarily lead to self-improvement and for all we know Budd will drive right back to New York under the same pretenses of temporary freedom. Whether or not Gallo's portrait of male isolation and passivity is hopeful in the end is not what is important; what remains is aesthetically potent, thematically simple, and emotionally charged use of cinema to envision an attractive man's crushing inability to share intimacy with women.

Question of the Week

Well, I was going to post some kind of deep, philosophical question tonight, but I got distracted by the Ebert & Roeper summer movie recap and decided, "What the hell, I'm feeling lazy..." So here goes:

What do you think of this summer's blockbuster season? The highlights? The lowlights? Share your thoughts and feelings about the summer films of 2004.

As always, this question is open to all blog members and readers, so reply early and often. Stay tuned, later this week I will open up the latest installment of the Milk Plus Canon, 1980-84. So get your lists ready.

Control Room & The Corporation

I’d like to think of myself as a “glass half-full” kind of guy (though to be fair, I usually act like a “glass half-empty” kind of guy), so I try to look for an upside in just about any situation, and I think I’ve found something positive in the current state of world and national affairs. There is an upside to an increasingly polarized electorate, a slumping economy, persistent threat of terrorism, and an unpopular war. Yep, these are heady days indeed if you are the filmmakers behind high profile, left-leaning documentaries. Of course, we got Fahrenheit 9/11 earlier this summer, but what about Outfoxed: Rupert Murdoch’s War on Journalism, Control Room, The Corporation, and the soon to be released Yes Men? Having seen two of those films this week, along with my daily dosage of swing state BS and, thankfully, the corrective of The Daily Show, I’m beginning to personally feel like a recent Onion headline, “Nation’s Liberals Suffering From Outrage Fatigue.”

As you have probably guessed, the two films that I saw this week were the cinema verite-influenced Control Room by Jehane Noujaim (co-director of Startup.com) and the dense, sophisticated and frankly frightening The Corporation, directed by Jennifer Abbott and Mark Achbar (co-director of Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media). I saw the former last Sunday, and just when my outrage was beginning to return to normal levels, I had to go out and see The Corporation today. It is actually nice to see these two films almost a month and a half after seeing Fahrenheit 9/11, arguably one of the most important events in film and media history. For one thing, though I still think Fahrenheit 9/11 is an excellent polemical-essay, and is far superior in terms of actual entertainment value, its political analysis is somewhat haphazard and unfocused, at least relative to Control Room and The Corporation, both of which I regard as superior political films.

Control Room Control Room may seem apolitical and objective on the surface, but it is just as polemical as Fahrenheit 9/11, questioning the very notion of media objectivity, how the war in Iraq was really fought, and most damningly, implying that the Administration and/or military effectively murdered an Al-Jazeera reporter when American warplanes bombed the Al-Jazeera Baghdad bureau, not to mention the offices of another Arab-language news channel which was critical of the war, and the Palestine Hotel, temporary home base to many non-embedded (i.e. non-stage managed) journalists, all at roughly the same time (Noujaim helpfully includes a scene earlier in the film where the Al-Jazeera General Manager repeatedly asks his staff whether or not they have transmitted the coordinates of their bureau offices in Iraq).

Control Room, most importantly in my opinion, humanizes the much maligned (at least by the American and British governments) Al-Jazeera satellite news network. Now if you listened to Donald Rumsfeld or the military-administration spokesman du jour, you’d think that Al-Jazeera was transmitting from a cave somewhere in the Middle East with an American flag burning as a backdrop and Osama Bin Laden on speed dial. While Al-Jazeera does clearly play to pan-Arab nationalism, the people behind the network, unsurprisingly, emerge as thoughtful, rational Western-trained professionals who express confidence in the concept of democracy, the American Dream, the American Constitution, and the American People, though not the Bush Administration or its policies. The military bureaucracy of CENTCOM fairs far worse (it is too bad for us that the American journalists covering CENTCOM did not include their rampant skepticism and cynicism, on display throughout Control Room, in their actual dispatches) with the exception of Lt. Josh Rushing, a Marine PR officer and media liaison who works closely throughout the film with the Al-Jazeera journalists, striking up a friendly, professional relationship with his charges, refreshingly professing his frustration with media spin and bias, and coming to a mutual understanding regarding the multiple POVs (especially in regards to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict) on display in the film. In other words, he’s pretty much a perfect spokesman for a military fighting multiple wars against Arabs and Muslims. Of course, our government, in its infinite wisdom has tried to muzzle Rushing. Our tax dollars at work people!

Now The Corporation was a like a really long, really scary version of PBS’s Frontline, but with a more sophisticated usage of edited found footage employed for satirical purposes (especially 50s and 60s era industrial films). The Corporation is a somewhat dry treatise designed to scare the bejezus out of you (right away, the film overwhelms you with an ominous, percussive score, a rapid montage of black and white corporate logos, and an eerily measured voice-over narrator whose voice is hardly comforting) packed with dense facts, archival footage, and talking heads interviews from both the Left (Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, Naomi Klein, Michael Moore, etc.) and Right (Milton Friedman, some conservative think tank guys, a bunch of CEOs). The first hour or so is the most powerful, as the film traces the legal and historical conceptions of the corporation up to the modern day. Playing on the concept of the corporation as a “legal person,” the film proceeds, with great effect, to use both the DSM, the many, many documented case studies, and the opinion of noted FBI psychiatrist Robert Hare to diagnose “ the corporation” with a psychopathic personality disorder. The most terrifying aspect is how convincing the filmmaker’s arguments truly are.

Pointing to the systematic sickness of the corporate system, the remaining hour and half becomes more diffuse, as The Corporation expands its scope to touch upon many relevant topics. From that point on, The Corporation is basically a series of related short-films organized around a singular topic such as corporate collusion with dictatorships, increasingly pervasive marketing (especially towards children), the dissolution of the independent media, and the corruption of the political process. The strength of these individual sections vary, and consequentially the film loses some of its power, but then there is another startling fact or admission which keeps you interested through the remainder of the film’s 145 minute running time.

For the most part, the film argues that internal reform is a remote possibility, if not outright impossible (the CEO of textile firm Interface, Ray Anderson, being the notable exception presented in the film; but as I watched the film, I had to wonder if profits fall too far, how long will the shareholders keep the altruistic Anderson in charge), and that external, grassroots pressure is necessary to keep corporate power in check. By the end of the documentary, after watching several successful instances of resistance to the corporate agenda, I was even critically thinking about my own place in the corporation I work for (Michael Moore makes a salient point about how we do not personally realize what kind of effect we are ultimately having). Given the film’s implications, The Corporation is perhaps the most effective horror film I’ve seen in a long time.

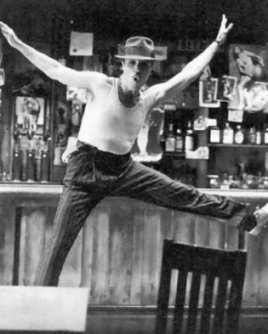

Pennies From Heaven

Pennies From Heaven Pennies From Heaven, 1981 (dir. Herbert Ross, starring Steve Martin, Bernadette Peters and Christopher Walken).

Pennies from Heaven played recently at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood and I missed it; shortly after that it was released on DVD and there was a lot of discussion about the film on an e-mail discussion list that I'm on, including the descriptions "revisionist deconstruction of Depression-era musicals" and "noir musical." I was intrigued, to say the least, so I put the DVD in my Netflix queue to see what the fuss was all about.

The film was a box office stinker when it was originally released in 1981, and while I didn't think it was a rotten movie, I can certainly see why it failed, especially following the enormous success of the previous screen pairing of Steve Martin and Bernadette Peters, The Jerk. Audiences went to the theater expecting laughs, and instead they got a depressing story and unsettling, overlong lip-synch and dance numbers (even for me, and I'm a big fan of movie musicals, especially those of the Depression era).

Steve Martin plays Arthur, a sheet music salesman during the Great Depression. He's unhappy with his home life (married to the frigid Joan, played by Jessica Harper), he's unhappy with his job despite an undying belief that he is uniquely qualified to sell songs, and he's unhappy with everything in general. He wants life to be the way it is in the songs he sells – the love, the happy endings, the good times just around the corner. On the road for his job, he meets a kindred spirit in Eileen, a forlorn schoolteacher, and they fall in love – but not the way people fall in love in the songs, not the hearts and flowers and walking on air, but sex and unplanned pregnancies and heartbreak.

Along the way, the audience glimpses the innermost feelings of the characters through song and dance – but instead of actually singing, they're lip-synching to original recordings popular songs of the day, such as "My Baby Said Yes" and "Did You Ever See a Dream Walking."

First, the good stuff. The undeniable highlight of the film is Christopher Walken's all-too-brief appearance as Tom, a pimp who coaxes Eileen into a life of whoredom. Tom is maybe the only honest character in the film; he knows who he is and what he is, and he makes no bones about it and no apologies for it either. Walken gives the role a quiet, understated menace that's chilling. If it was just the acting in his one sequence, he'd still steal the picture, but add on top of that the absolutely delightful tap/strip dance to Cole Porter's "Let's Misbehave" which is far and away the most fun number in the movie.

Bernadette Peters never had much of a movie career (this movie's reputation probably didn't help much), which is too bad because I think she's a tremendous actress – even without her singing voice that's made her such a Broadway diva. The character of Eileen is the only one in the movie that I felt sympathy for. In fact, in the first half of the film, every time she was on screen I practically wanted to cry; she was so, so sad. As worse and worse things keep happening to her; Eileen adapts to the shitty hand life deals with her in the only way she can, going from lonely schoolmarm to jaded whore in the span of 90 minutes, and is completely believeable every step of the way.

I'm a big fan of Steve Martin's, despite his recent insistence on making his living on low-level remakes like Cheaper by the Dozen and Father of the Bride. He's the best Oscar host in recent memory, and he makes up for his box office mediocrity with his books and plays – if Bringing Down the House makes it possible for him to do more stuff like Picasso at the Lapin Agile, more power to him. Pennies from Heaven was a gutsy move on his part, an attempt to break away from "the Ramblin' Guy" and move towards a more serious acting career.

Unfortunately – his acting kind of stinks in this movie. He still gives in to the wild 'n' crazy guy persona a couple of times, almost as if he doesn't realize it. He treats his lip-synch sequences as if he's goofing on us, going for laughs, instead of playing it straight. He's uncomfortable in his dramatic scenes. It's not surprising; this is his first role with any dramatic guts to it, and he's still trying to find his way. Six years later he found the right blend of comedy and drama in Roxanne, which served to be the dramatic stepping stone he was trying to find in this film.

It doesn't help that Arthur is a completely unsympathetic character. Leaving aside for the moment his hideous treatment of poor sad Eileen, what we're supposed to like about Arthur is his unflagging belief in himself and his dream for something better. At the beginning of the film he has a number of scenes stating (overstating even) his confidence in himself as a salesman – he knows what sells, he knows songs and he knows music and he knows what the public wants, and he's going to make it in this tough world.

The problem is, he's a lousy salesman. We see him failing to sell over and over again. He somehow convinces his wife to put up the money for his own music store, and he still can't sell, the store is constantly empty. So his dogged belief in his ability as a salesman doesn't come off as gumption and moxie, instead he comes off as delusional.

Also, there's something aggravating about a guy who is constantly telling himself, "If I just have this one thing I'll be happy. Okay, now I have this thing, if I can only get THAT one thing, I'll be happy. Okay, if I can just have this thing, that thing and that OTHER thing over there, I'll be happy." Not for nothing, but this is the Great Depression here. Arthur's a lot better off than half the population – he's got a home, he's got a steady job, he and his wife have a nest egg (even if they don't have a good sex life, or indeed a sex life of any kind). He's got a right to be ambitious and to dream for something better, of course, but the fact that he can't appreciate what he has is a little exasperating to me.

And then he's such a bastard to Eileen, knocking her up and then leaving her flat and alone, causing her to lose her job and move on to a life of turning tricks; he keeps coming back to her and messing her up even more. He pisses me off. He doesn't deserve the happy ending he keeps striving for. He hasn't done anything to earn it.

The musicals of the '30s are enjoyable, in part because they don't dwell on misfortune and squalor and poverty. There's just singing and dancing, and snappy chorus girls like Ginger Rogers, and fresh chorus boys like Dick Powell, and wide-eyed ingenues like Ruby Keeler. We don't see them trying to scrape together enough pennies to get a hot dog at the corner stand or sneaking into the boarding house because they're behind on their rent. Audiences of the '30s didn't need to see stuff like that, or want to see stuff like that; they lived it.

The revisionist approach to Pennies From Heaven works on some levels, showing the kind of desperation that was really going on behind all the box office fluff of Astaire & Rogers and Busby Berkeley. The costume design, art direction, cinematography and choreography is all beyond reproach; it captures the look and feel of the '30s pretty well. But I hoped it would have a bit more enchantment to it, a bit more movie magic. Musicals need joy. They don't have to be about happy subjects, but there needs to be joy. Excepting from a few scenes (Walken's number is one; the Astaire/Rogers number is another), Pennies from Heaven is missing that key ingredient.

Pennies from Heaven is an interesting experiment, and while I appreciate the valiant effort of all parties to do something different, in the final analysis its ambition is too big and too unrealistic, not unlike Arthur's ambitions.

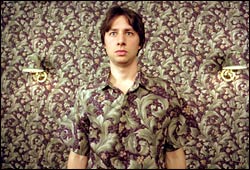

Garden State

I just realized something the other day, usually I dislike movies that were directed by people whose primary profession is acting. I’m not sure where this dislike stems from, and there are many notable exceptions, such as my love for the films of Clint Eastwood. That said, the newest exception is Scrubs (a personal favorite, by the way) star Zach Braff’s feature writing-directing debut Garden State.

Now, movies that get heaps of Sundance buzz and which are regularly described as “quirky” usually fill me with a sort of dread that keeps me away from the theater, so I was pleasantly surprised that the film actually lived up to the buzz and that it was “quirky” in an amusing sort of way (most of the time). Sure, sure there are things I did not like about the film, but those are the sort of things I usually expect from a first time writer-director. Braff proves to have a keen visual sense and expert, deadpan comic timing (accentuated by both the acting and editing), so its hard to quibble with what I perceived to be his overuse of slo-mo and indie rock tunes (though I did like the usage of The Shins song during the first encounter between Adam and Sam).

Braff’s writing is acute, capturing the driftless sensibility of those who are just floating through life (I read this article about Braff in the newspaper today, and it talks a lot about his inspiration for much of the content in the film). Basically an episodic narrative set over the course of four days, Braff’s script is content to follow the characters around and observe how they relate to each other, slowly parsing out the character’s often tragic backstory, while weaving both a subtle character arc (Adam’s emergence from a lithium induced haze, leading him to actually begin to feel and make decisions for himself) and a splendid movie romance. The story is simple. Zach Braff plays Adam Largeman, a not too successful television actor, who returns to his hometown in suburban New Jersey after an absence of nine years to attend the funeral of his crippled mother. The emotionally numb Adam finds his hometown and former high school friends in a sort of stasis, mostly going nowhere since they are still mired in a sex-crazed, pill-popping, dope-smoking adolescence, especially the guy who made millions by lucking into a patent for “silent velcro” (this kind of stasis extends beyond Adam’s friends, with the exception of the hallway bathroom, Adam’s parents house is preserved exactly the same as before he left, kind of like a museum)  . Having left his medication back in his sterile, LA apartment, Adam decides to experiment with his life, hanging out with former friends and meeting a young woman named Samantha, who he first befriends and then falls in love with. The final day of Adam’s visit is filled with a sort of meandering quest through the eccentric hinterlands of New Jersey, a quest prompted by his former best friend, Mark, played by the always measured and excellent Peter Skarsgaard, and the film concludes with an appropriately heady, romantic denouement.

Befitting a working actor, Braff writes several scenes and monologues which showcase the acting talent of his cast, especially Natalie Portman who really shines in her role as Adam’s love interest Samantha, an extremely adorable, vivacious free-spirit who happens to be an epileptic ex-figure skater and pathological liar, and is probably more responsible for Adam’s new attitude towards life than any sort of drug withdrawal. Her performance in Garden State pretty much erased my Star Wars prequel-induced perception of her as a wooden actress.

The relationship between Adam and Sam is my absolute favorite aspect of the film, and the primary reason why I rate is so highly. Braff and Portman have a lot of chemistry together, and their developing romance is a bit sad (actually heartbreaking when tearful Sam bids Adam goodbye, but then I’m always a sucker for girls crying), often a bit silly, and very romantic. In other words, it is very believable, and Braff services the romantic aspects of his story with many, many well-drawn, intimate scenes between the two of them, such as their scenes together in the pool or in the bathtub. I loved it when Adam actually got angry with Mark during their quest, accusing him of trying to corrupt the “innocent” Sam, which prompts her realization that he is trying to protect her and that “he really likes me!”

My one complaint, in terms of the screenplay, involves Adam’s relationship with his psychiatrist father, played with a funereal pall by Ian Holm (which in my mind, predates his wife’s possible suicidal death). Adam spends most of the film trying to avoid his father, and even though he is a lurking presence in the film, we learn little about him (we learn much more about Adam’s deceased mother), other than he was desperately trying to fix his family by forcing them into some sort of state of mythical happiness. However, we only learn this from what Adam states, and is never really depicted in the film (though prior events allude to this point). Consequentially, when Adam finally confronts his father, his assertion of control over his life and emotional catharsis seems too easy and strikes a false note, as do several other statements of purpose throughout the film (it is sometimes akin to being hit on the head with a hammer, since the points are often very obviously stated).

Still, Garden State is a very auspicious debut for Braff, and while I look forward to Braff’s return to Scrubs, I’m also looking forward to his next film. Not only that, I’m actually looking forward to Natalie Portman’s next, non- Star Wars film; I saw the trailer for Closer yesterday before Garden State; this has to be the first time in a long time I’m excited for a movie by Mike Nichols.

Just a lark, My Top 10 Most Romantic Couples of 2004

1. Jesse and Celine, Before Sunset

2. Adam and Sam, Garden State

3. Jong-du and Gong-ju, Oasis

4. Joel and Clementine, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

5. Seibei and Tomoe, Twilight Samurai

6. Kumar and his big bag of pot, Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle

7. Lucius and Ivy, The Village

8. Peter and Mary Jane, Spider Man 2

9. Tsai Ming-liang and old movie houses, Goodbye, Dragon Inn

10. Henry and Lucy, 50 First Dates

|

|