Suspended Animation

We'll make this one quick: "Suspended Animation" would have been a terrific film if director John Hancock could have whittled down all the superfluous, boring parts and concentrated on the tense hostage scenes that serve as this film's bread-n-butter. Of course, that would have also made the film twenty minutes long at best, not to mention comprised entirely of violent scenes minus any context... but at least I'd have nothing to complain about. At two hours, though, and with more padding than your father's old recliner, there's only one possible reaction: Boy, this movie's dumb.

How dumb is it? Well, let's take a look at that title. Seems like a solid title for a grisly thriller until it's revealed that the hero makes animated movies (ones nobody seems to have heard of, despite his obvious wealth) and he goes jet-skiing at the beginning of the film, thus putting him in harm's way, because he's hit a creative block with his latest film. So instead we're saddled with a clumsy bit of wordplay that somebody must have thought was awfully clever. You get that a lot here. One instance: Tom (our hero), having been captured and tied down by two deranged, murderous and possibly cannibalistic sisters with a cupboard full of pickled parts, has to think of a way out. He pleads for his life and mentions that he'll be missed in Hollywood because, you know, he's a famous animator and all. He then offers to put the two in his next movie, saying he can whip up quick sketches of how cool they'd look if only his writing hand was free. Sounds plausible on paper, yes; however, in the enacting it just sounds silly. Even better, though, is the fact that the sisters buy into his codswallop and agree to free his hand instead of saying "Yeah right" and gutting him on the spot. Making your villains appear to be total imbiciles, I have found, is not exactly a surefire way to keep the audience's interest.

Compounding the problem is that two-hour running time, which wouldn't be that big a deal if the film didn't reach a perfectly good climax forty minutes in. Left with over an hour to go, Hancock spins his wheels ferociously while looking for somewhere -- anywhere -- for the story to go. For a while, he seems to want to push it into "Stendahl Syndrome" territory, with Tom appearing increasingly unhinged as he stalks Clara, a young actress who may or may not be the long-lost daughter of one of the insane sisters; inevitably, he pulls back from that abyss and settles into an insanity-runs-in-the-family groove, throwing the spotlight on Clara's mean-natured son Sandor. And yet, when this plotline reaches a conclusion, the movie still isn't over. It's about this time that I started wondering "Where else can this go?" Where exactly it does head in its last twenty minutes is not for me to reveal, but I will say that it's both fairly riveting and punch-yourself-in-the-head stupid. No doubt the rambling story worked better in the source novel (written by Hancock's wife), if only because there's room to stretch things out in print and you can use stylistic devices to punch up a less-than-stellar narrative. Hancock only has a camera, his adequate directorial talents, an inadequate budget (everything looks vaguely TV) and a handful of really bad actors to try and sell this drivel. Why this didn't go straight to video is beyond me.

In My Skin

In My Skin, actress

Marina de Van’s feature length debut, takes the irresistible, irritating habit of scab picking to incredibly disturbing new heights. When Esther (de Van) stumbles in the backyard of a party it’s not until later that night she realizes some piece of garden detritus gashed a nasty chunk out of her leg. In fascination Esther picks at it, feeling nothing. Her doctor, her boyfriend Vincent (Laurent Lucas), and her girlfriend at work Sandrine (Lea Drucker) all think it abnormally weird that she was not in pain; she admits she is neither numb or shocked, her wound simply did not hurt her. One day at work Esther gets a strange desire, and she retreats into a storage closet to scratch and pick at her healing leg wound. Finding the sensation intriguing and pleasuring Esther finds a metal object on the floor and picks harder, deeper. Getting more involved in the sensation Esther makes the critical jump from invigorating her old wound to using the metal object to cut new gouges in her leg.

At first Esther declares her cutting like she found a mysterious sexual pleasure to share, but Vincent and Sandrine are more worried about rationalily than sensations and they pester Esther with questions. Why can’t you feel pain? Don’t you think that’s weird? Can you feel this? Do you need to see a doctor, get pills? Are you depressed? Esther, like de Van the filmmaker, steadfastly refuses to rationalize what she is doing and provide answers to her abnormal behavior. All the more baffling is Esther’s psychological motivation. She has a warm and caring boyfriend and is advancing quickly in a job practically tailored for her special interests. Early scenes in the film with Esther pulling at the loose

flesh around her belly and playing and tearing her nylon stockings from her leg emphasize her growing interest in literally getting beneath the surface of herself.

Despite promising Vincent she will stop her self-mutilation Esther increases the intensity of her stimulation. She gets distracted at a business dinner with her arm goes numb, appearing disconnected from her body; only a jabbing with a steak knife and a gentle sucking reattaches the arm to Esther’s body. With previous mutilations already appearing masturbatory through de Van’s careful framing and her quasi-erotic performance, Esther pushes herself by getting a hotel room and digging deep, deep into her arms and legs, tearing small chunks of skin out of herself. As she gouges open a new wound on her unharmed leg Esther curls up into a fetal position, lapping at her wound as her twisted leg dribbles warm blood on her face in a disconcerting picture of self-absorbtion.

With this scene and a handful of subjective point-of-view shots of Esther disoriented by the exterior world, one must read Esther’s behavior as finding sudden, strange self-fascination. This can especially be seen as Esther’s exploration of her wounds turns into self-consumptive cannibalism, as she eventually eats bits she gouges

out of herself, and later gnaws on her arm and leg. As Esther’s fascination evolves de Van’s film, which wisely turns into itself instead of giving any hint at psychological explanations, grows more abstract and ambitious along with her. Utilizing an inexplicable split screen technique Esther becomes as interested in her own image as the audience is-presuming the viewers have not already walked out at the film’s incredibly unsettling visual depiction-peering at her bleeding body in a mirror and taking pictures of her mutilations, eventually culminating in her attempts to lovingly preserve severed pieces of skin.

Though missing a clear conclusion-the film ends in a bizarre middle ground between Esther reentering the exterior world and Esther becoming lost in herself-

In My Skin remains a searing and marvelously directed picture of growing self-obsession. Supremely unsettling is de Van’s all involved aspect in the film, from writing and directing it, as well as giving a beautiful, mysterious, and squirm-worthy performance, and then topping it off by including vague self-referentiality through both Esther’s photographs and the title’s implication of the film being a completely personal, intimate work. This is indeed the effect, letting the audience in on an unusual path of self-searching. Though Esther never seems to find what she is looking for, if she is really looking for anything at all, her search is horrific and disturbingly, revealing that self-satisfaction may only come from within.

Love Actually

Call me crazy, but I think Richard Curtis has a thing for love; Curtis, the screenwriter auteur behind such hit British films as

Four Weddings and Funeral,

Notting Hill and

Bridget Jones’s Diary (and thus the person Hugh Grant is most indebted to for his stardom, having written the majority of his best roles), in his foray as a director has crafted this little paean to love in it’s many different variations. Actually, a “little paean” is a bit of an understatement, as

Love Actually is a sprawling, two hour, fifteen minute ode to LOVE! Let’s not stop there, in fact, It’s is a big, wet, sloppy kiss on the lips of LOVE! Which isn’t to say that it’s bad, despite some opening reservations (the film opens with shots of loved ones greeting each other at the arrival gate of Heathrow Airport, while Hugh Grant muses in voice-over that even in the post-9/11 word, loves rules the world),

Love Actually turned into what I expected it to be, a sentimental, romantic piffle, but one, like the rest of Curtis’s films, that is extremely enjoyable to watch.

Given the huge cast, which sprawls over nine, vaguely connected plotlines, many critics have taken to calling the film Altmanesque, but I think this is lazy misnomer. For one thing, as I sat in the theater, I realized that this film was

completely devoid of cynicism towards the romantic notions which fuels it’s plot (not that Curtis is completely dewy-eyed when it comes to love, but I’ll get to that later), but more importantly, Curtis wraps up all but two of it’s storylines in a big, nice bow in the end (did I mention, that most of the action takes place over the five weeks which precedes Christmas). All very unAltman-like if you ask me, but I digress. Without further ado, the storylines:

* The film actually opens with a shot of a recording studio (completely off the subject, but one of the recording engineers is also one of the tech guys in

MI-5). Fiftyish, drug-addled ex-rockstar Billy Mack (Bill Nighy; pretty much think Keith Richards gone to seed, if that is possible) attempts to cash in on his fading popularity by recording a new, Christmas version of the Troggs song “Love is All Around”. Nighy pretty much steals the show as the hilariously vulgar Mack, who spends the majority of the film trying to promote his new single. However, much to the consternation of his every loyal manager, Joe, Mack, who adopts a “who gives a fuck” attitude and proceeds to shoot from the hip, disparaging his single and making outrageous statements (at one point, when being interviewed on a British version of TRL, he counsels children not to buy drugs, instead becoming pop stars because then people will give you drugs for free; at another point, he pledges to a talkshow host that if his single reaches #1, he will perform completely naked, and then drops his pants to give the host an up close view of his willy, the game hosts comeback is hilarious). Surprisingly, his tell it like it is approach pays off, and his single becomes #1, which results in his invitation to a posh Christmas party. The payoff for this storyline, in regards to the rest of the plot, is when Mack has an epiphany, leaves the party, and joins his manager Joe, because he loves the man, and Christmas is for spending time with your loved ones (though this Xmas, they’re going to get drunk and watch porn). Mack’s share of the narrative thread never really interacts with any of the others; some of the characters are shown watching him on TV, but that is about it, though even this plays a small, but crucial role in another plotline. Though this narrative thread falls far short of self-reflexive criticism, it is interesting that Curtis created a character who pretty much creates a crassly sentimental pop tune for the sole purpose of making lots of money, and then spends the remainder of the film mocking that very same attempt. Still, whenever the film veered too far into gooiness, it was a nice change of pace to cut to Mack spouting some sort of profanity.

*Hugh Grant plays a newly elected, but unmarried, Prime Minister who finds himself falling in love with a newly hired secretary at 10 Downing Street named Natalie (Martine McCutcheon).

I guess this narrative thread is something of a British version of

The American President (even with it’s own liberal fantasy), though Grant tries very hard to resist his romantic impulses, especially after his feelings interfere (though for the better) with matters of state. He catches the President of the United States (Billy Bob Thorton) putting the moves on Natalie, prompting a fit of jealousy. I always found myself kind of incredulous when I read various S&S articles, written from a cultural studies perspective, that examined Anglo-American relations through the perspective of Curtis’s films, but in

Love Actually the subtext has clearly become the text. Even though he himself counseled a conciliatory attitude towards the Americans, Grant’s PM is so outraged by President’s smug sense of superiority and entitlement (both geopolitically and sexually), that during their joint press conference, Grant sticks up for the UK and declares it’s “special relationship” with the US to be a bad one. I kind of perked up at that moment, as I did not expect a riposte to Tony Blair and Dubya (and I’m sure it’s no coincidence that they cast a Southern actor in the part of the President) in a film designed to be a crowd-pleasing romantic comedy (but then, both Universal and Studio Canal are owned by Viviendi, which is a French film, go figure). After that little showdown, the formerly precarious PM solidifies his popularity among the Brits, but ends up having the fetching McCutcheon (which is also something of a cross-class romance, with the working-class McCutcheon and the upper-class Grant), who everyone often refers to as “chubby” (I didn’t think so, but I thought that might be some kind of Clintonian in-joke), reassigned. When he receives her Christmas card, he has a change of heart, and drives down to her London neighborhood. Since he doesn’t know her address, he turns to knocking on random doors; of course, the PM of Britain, with his security detail in tow, knocking on strangers doors is played for comedy (my favorite is when the trio of little girls asks them to sing Christmas carols, and he and his bodyguard shrug their shoulders and agree). Eventually, they do find Natalie but everyone is in a rush to go to the school Christmas pageant (where several of the other plotlines conclude, and which includes a overly wacky nativity scene complete with lobsters and an octopus), where, despite all their attempts at secrecy, there first kiss is seen by the entire crowd, much to their thunderous applause.

*The PM’s sister, Karen (Emma Thompson) is married to a magazine editor named Harry (Alan Rickman); though outwardly happily married with two children, Harry’s attentions are beginning to wander as his personal assistant, Mia (who, by the way, also happens to be Natalie’s next door neighbor, so she too briefly meets the PM), begins to openly propose a relationship that is anything but professional. The irony of this situation is that the ostensibly happily married couple (the only ones featured in the entire movie, other than the newlyweds Peter and Juliet) are each giving counsel to another lovestruck friend. As Christmas approaches, the affair between Harry and Mia heats up (at the company Christmas party, Mia and Harry dance way to close, which is seen by Karen), though to Curtis’s credit, we never really learn the true extent of Harry’s infidelity. Karen becomes aware of the affair when she finds a gold locket in Harry’s coat pocket (in an earlier scene at a department store, Harry, briefly left alone by Karen, attempts to buy the same locket from a fastidious clerk, played by Rowan Atkinson, who later reappears in another plotline as something of a fairy-godmother), and mistakenly thinks it is a gift for her. When she realizes his duplicity on Christmas Eve, she manages to collect herself, only to later confront her husband after their children’s Christmas Pageant. This particular narrative thread, besides providing the irony I pointed out above, is something of a counterpoint to the other stories. It is one of the segments which doesn’t have a firm, romantic conclusion, instead the final status of their relationship is left kind of ambiguous. In the film’s coda (which is also set at the arrival gate of Heathrow), we are shown that Karen and Harry are still together, but things are now cool between them, as if they were going through the motions.

*At the magazine, Harry romantically counsels an expatriate American woman named Sarah (Laura Linney), who is madly in love with one of the designers, Karl. It’s an open secret in the office, one known even to Karl, so Harry keeps pushing Sarah, who is something of a wallflower, to ask Karl out for a drink. She repeatedly demurs, and it is kind of weird that she repeatedly receives cellphone calls from someone she refers to as “babe” and “darling,” though the identity of the caller is not revealed until much later. It is at the company Christmas Party that Karl finally asks Sarah to dance, and they return to her place together. It’s a great moment, when an ecstatic Linney secretly does a little happy dance while Karl waits at her door, and then has him wait for ten seconds as she tidies up her bedroom, kissing her teddy bear and then throwing it underneath her bed. Unfortunately, there attempts at love making is twice interrupted by the mysterious cellphone caller, who is finally revealed to be Linney’s mentally unstable, institutionalized brother, and there relationship is seemingly aborted before it really even had a chance to begin. Sarah’s story is the real-downer of the film (along with the story of Karen and Harry), and she is the only character not to appear in the film’s romantic coda (instead, her story ends on Christmas Eve as she visits her brother in the institution; apparently, her love for the brother has permanently frustrated her romantic desire).

*Karen, on the other hand, is a good friend to Daniel (Liam Neeson), whose young wife has just passed away (the funeral scene is not quite up to

Four Weddings and a Funeral, with WH Auden being replaced with the Bay City Rollers, though it does setup a joke about Claudia Schiffer that is paid off near the film’s conclusion), leaving him to care for his adolescent stepson, Sam. The grieving widower is perplexed by his stepson, who has withdrawn following his mother’s death. Fearing the worst, Daniel, acting on Karen’s advice, sits down and has a talk with his stepson, who confesses to being in love with the coolest girl in school, an American exchange student, much to Daniel’s happy relief. Daniel and Sam are soon revealed to be starry-eyed romantics cut from the same cloth (at one point, they even watch

Titanic together, acting out the famous scene at the bow), commiserating in the “agony of love.” Bonding over their frank discussion of both the positive and negative aspects of love (and Curtis is smart to have his characters acknowledge that they can often be the very same thing) and unabashed romanticism, Daniel and Sam hatch a plot to impress Sam’s crush, which reinvigorates them both, despite the lack of sleep that the plan brings (Sam learns the drums, using the logic that musicians often get the girl). Sam’s performance at the Christmas Pageant initially appears fruitless, but with his step -dad’s encouragement (who also meets his new love in the guise of another single mother, played by Claudia Schiffer), the two of them whisk off to Heathrow, so that Sam can finally talk to the girl of his dreams.

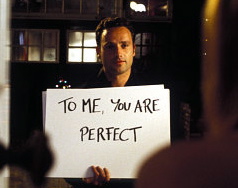

*Laura Linney’s Sarah also happens to be friends with a couple of young Londoners who are getting married (Chiwetel Ejiofor as Peter, and Keira Knightley as Juliet) in the film’s opening segments. Peter’s best friend, and best man, is Mark (Andrew Lincoln), who seems kind of aloof around Juliet, despite the quirky surprise that he arranges for the couple at their wedding (he strategically hides musicians in the chapel, who pop up to play the Beatles “Love is All You Need” after the vows are exchanged). Curtis uses a misdirect to make the audience (or at least me) think that Mark is gay, and secretly in love with Peter; thus his aloofness towards Juliet is caused by jealousy. That is, until one day, Juliet comes looking for a decent video of her wedding. She comes to Mark’s apartment, and watches his video, which turns out to be a video love poem to the oh so beautiful face of Keira Knightley (I was so turned around by the misdirect, that I thought the video would be all Peter).

She is shocked, and he is embarrassed, with the situation being left in limbo until this narrative thread’s Christmas Eve conclusion, when, in a romantic gesture sure to be copied a million, billion times this Valentine’s Day, Mark comes to Peter and Juliet’s apartment, and tells her how he really feels about her via a series of handwritten placards. It’s sweet because Mark flat out declares that he is not going to try to breakup his best friends marriage, but that he loves her any ways, and he is rewarded by Juliet with a friendly Christmas Eve kiss. It was wise to leave it at that, as any other way would have introduced a queasy factor into the segment, throwing it into the downer column.

*Colin Firth’s Jamie, a writer of mystery thrillers, is also friends with Peter, Juliet, and Mark. Happening to live just around the corner from the chapel where the wedding takes place, Jamie pops back into his apartment between the ceremony and reception, to unexpectedly find his “sick” girlfriend (whom he repeatedly declared his love to) cheating on him with his brother. Devastated, Jamie retreats to a cottage in Provence to write, where he is attended to by his Portuguese maid Aurelia (Lucia Moniz). Though neither can speak each others language, the two of them fall in love with each other (the fact that the two of them echo each other’s thoughts, even though they can’t understand each other is played effectively for both laughs and sweetness). When he returns to London, he plunges himself into a crash course in Portuguese, and on Christmas Eve, instead of spending time with his estranged family, he impulsively flies to Lisbon to ask Aurelia to marry him. This segment had perhaps the corniest ending (which is not helped by the fact that Curtis cross-cuts between the other stories in London, building to an outright crescendo of LOVE), with Jamie fumbling to convey his feelings to Aurelia’s family, resulting in a cascading series of linguistic guffaws, which then results in a huge crowd of confused and curious Portuguese people following Jamie to the restaurant where Aurelia works. There he asks her to marry him, and she says “yes” in English (again, the two of them echo each others feelings and ideas). It’s a veritable orgy of love.

*Speaking of orgies, there a short segment between a pair of porn stand-ins. It’s pretty much a one-joke premise: despite being completely naked and simulating various kinds of sex, the two of them carry on an easygoing conversation. Even thought it’s a one-joke premise, it does have a nice pay off, when on their first real date, they have trouble, due to shyness, with the goodnight kiss.

*One of the assistant directors at the porno shoot is also friends with an uncouth, British slacker named Colin (Kris Marshall, kind of think of Puck from

The Real World but with a British accent), who hatches an idea. He figures he can get laid much easier in America, where the ratio of women who would desire a guy with an English accent is much higher. Being that I saw this film in Madison, Wisconsin, Colin’s decision to travel to Wisconsin, of all places in the US, got the biggest laughs of the entire movie, as did his decision to travel to Milwaukee. Yes, British readers, your chances of scoring in Wisconsin do go up when you have an accent, but it’s highly doubtful that you’ll find girls like

24’s Elisha Cuthbert or

American Wedding’s January Jones in your average Wisconsin bar (though, the bar actually does look fairly real, if a bit too big and bright). Maybe it’s just because I live in Wisconsin, but I found Curtis’s play on stereotypes to be pretty funny (also the look on the assistant director’s face, who called his friends plan completely “crazy,” when he meets Colin at Heathrow, accompanied by Shannon Elizabeth and Denise Richards).

Though I’ve alluded it to the above descriptions, Curtis’s decision to cross-cut between the stories, from the darker-edged tales of romantic woe (Sarah, Karen and Harry), to the raunchy, comedic tales (Billy Mack, Colin), and unabashed romantic stories (the PM, Jamie and Aurelia, Juliet and Mark, Daniel and Sam) keeps the viewer from overdosing on the sugary fable (it’s certainly more adult that Curtis makes concessions to the idea that love can be difficult and painful). It’s certainly a crowd-pleaser, but in the best sense of the word: well acted, by many charming actors (Laura Linney has never been so adorable; not to mention the perennially charming Hugh Grant, loved his dance through the halls of 10 Downing Street, and Colin Firth), very funny (courtesy of Curtis, who is a brilliant writer of romantic comedy), and often very touching.