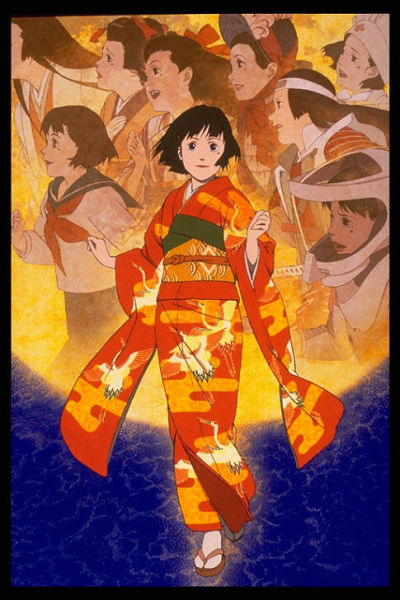

Millennium Actress

I almost did not go to Satoshi Kon’s masterful animated film

Millennium Actress. When I first heard on Thursday that the film was being screened here this week, I made the decision not to go; other than Hiyao Miyazaki, I’m just not a big fan of Japanese animation, though I’ve seen plenty of anime on television and on DVD/VHS. However, I changed my mind after an AIM conversation with Phyrephox on Friday night, and I’m glad that I went, as

Millennium Actress has taken it’s place as my second favorite movie of 2003 (I guess it’s being released on DVD sometime within the next week or two for anyone who is interested).

The film is about a pair of documentary filmmakers, the middle-aged Genya Tachibana and his much younger cameraman Kyoji, who have arranged to meet and interview a reclusive former film star from the golden era of Japanese cinema, Chiyoko Fujiwara, who mysteriously and abruptly retired from acting at the height of her career. This premise allows Kon to plunge the trio, as well as the audience, into Chiyoko’s memories, along the way erasing the boundary between factual, objective reality and subjective fantasy. All frames of reference are carefully swept away, the film, taking full advantage of the plastic space-time properties of animation, abruptly changes time periods (from 15th Century Japan to the present day, spanning almost every major period of Japanese history in the interim), and seamlessly switches locales, moving back and forth between the present, the “real life” events of Chiyoko’s past, and historical sequences which Chiyoko, and various other characters, inhabit as if it was a lived-in reality (for convenience sake, I’m going to refer to these scenes as “film-reality”). Of course the boundaries between all three are quite fluid, when the viewer becomes accustomed to one level of reality, the film switches gears, moving the events to another reality entirely. One quickly realizes that the central narrative thread of the film, Chiyoko’s never-ending search for a young artist/political radical that she fell in love with when she was 17 (though she never learned his name, or clearly saw his face, which is plunged into shadow every time he appears on screen, he gives her a key, which is a “key to the most important thing in the world”), is an archetypal cinematic narrative of undying, romantic love, and not only does it appear in the reality of Chiyoko’s life, but time after time, it appears in the film-reality sequences, across genres, from jidaigeki, to gendaigeki, from monster films, to science-fiction.

The film actually begins with what appears to be a science-fiction story, an as yet unnamed woman (Chiyoko) is boarding a rocket ship to look for “him” despite the protests of another man; the audience is given no frame of reference, but as the rocket prepares to blast off, Kon changes perspective, pulling back and allowing the audience to see that Genya is watching the footage on an editing table (later we learn that this is footage from Chiyoko’s last, unfinished film), the sound effects of the film mingling with the rumblings of a minor earthquake that hits at that very moment (earthquakes occur frequently in the film, marking major points of transition for the characters, adding an additional mythic quality to the narrative). This is one of many examples of the film reindexing events into another level of reality, in another, Chiyoko’s mother attempts to arrange a marriage for her daughter, who refuses the proposals, but then the scene morphs into a scene from a contemporary domestic melodrama, Chiyoko’s mother being replaced by Eiko, an older actress at the studio who shared the same dismissive attitude towards Chiyoko’s romantic notions as her real mother did (there’s another later scene, where it appears that Chiyoko is vacuuming her husband’s study, but it turns into a movie set). And it is more than a one way street, elements from the film-reality begin to appear in her reality, the most important being a ghostly old crone, who cursed Chiyoko in a film-reality jidaigeki to love her lord for a thousand years, and whose reflections begins to appear in Chiyoko’s normal reality, a haunting presence which continually reminds Chiyoko of her true love.

What makes the film even more interesting, is that both Genya and Kyoji begin to appear in the narrative

, whether in the reality of the past, or the film-reality. At first, they stand back, observing the action from afar, like something of a chorus; Genya, who has proved to be a somewhat obsessive fan, invests so much of himself emotionally into whatever scene that he witnesses, whether reality or film-reality (in one scene, ostensibly from Chiyoko’s real life experience, she runs after a train, trying to see her love one final time, and a blubbering Genya confesses that he’s cried after watching this over fifty times), that he seems to find the entire thing natural (or at least, he’s nonplussed). Kyoji on the other hand, is totally bewildered by the experience. He provides much of the film’s comic relief, being quite ambivalent and befuddled by what is going on (if not downright sarcastic), not to mention terrified, in one scene the three of them move from the reality of 30s Manchuria, when Chiyoko’s train was attacked by bandits, to a burning feudal castle straight out of a jidaigeki, where Kyoji, still toting his HD camera, as he does throughout the film (in effect attempting to film memory) is almost dispatched by a volley of arrows, in a visual homage to the famous scene from Akira Kurosawa’s

Throne of Blood.

Eventually, being a witness is not enough for Genya, and he begins to appear in both film-reality and reality, repeatedly casting himself in the role of Chiyoko’s savior or benefactor, no matter what era or place (in one funny moment, Genya, having fended off a company of samurai in a 15th century forest, drags himself through the streets of late Tokugawa Kyoto, and Kyoji dryly asserts that he is dressed wrong for the era). At first, these intrusions are interrupted by a return to reality, where it seems a game Genya was play acting with Chiyoko, but soon this pretense is completely dropped, and Genya’s interjections into the story become more frequent (though Genya does sometimes return to the act of observing, as when he angrily watches director Otaki’s cheesy attempts to seduce Genya in the late 40s).

Genya’s own romantic fascination with Chiyoko, whom he idolizes and adores, is paralleled with Chiyoko’s own desire for her unknown love, and it too has a basis in reality, as Genya, in his youth, was an apprentice member of the Otaki Film Unit which produced all of Chiyoko’s films in the 1950s, so he was a witness to many of the same events. He even saved her life after an earthquake shook apart the set. This scene is particularly interesting because it is a reprise of the footage that opened the film (one of many reprises throughout the film, as there is a lot of narrative repetition), though this time it is Genya trying to talk Chiyoko out of piloting the rocket ship, and it is he who dejectedly watches Chiyoko from the control room before the film-reality breaks into reality, the earthquake intrudes, allowing Kon to again readjust the audiences perspective by revealing the film set. (I have to note that I loved how the film dissolved back and forth between the younger and older versions of characters, who even when the ages fluctuate, still resemble themselves much more than a live actor could accomplish; it was also interesting to note that the character of Chiyoko had three different actresses voice the part, one for each period of her life). It’s actually at this moment that Chiyoko leaves acting, when she sees the reflection of the old woman in visor of her helmet.

It’s actually the arrival of a former government agent, the man with the scarred face, who is first seen chasing the young activist through the snowy city streets (this scene is reprised almost exactly, but in the trappings of a samurai drama, and this time Genya intercedes, stopping him from killing Chikoyo, who is dressed as a geisha; the agent with the scarred faced reappears again and again, always as a nemesis, no matter what the time period, or whether the characters are in reality or film-reality) heralds the film’s most bravura sequence. He appears in the studio offices to beg Chikoyo’s forgiveness for what he did to her during the war, and he gives her a letter from the young radical, written during WWII, which sets her off on a quest to Hokkaido, to find her love, traveling hundreds of miles in a few minutes, a flurry of activity as Chikoyo , presented a complex set-piece of movement, sound, and color (Genya and Kyoji again reappear, sometimes shouting encouragement, other times, Genya directly assisting Chikoyo in her journey). In it’s most bizarre twist, the movement from Tokyo to Hokkaido transitions to the dusty-landscape of the moon (again, returning to the setting of Chikoyo’s final science fiction film), where an exhausted Chikoyo, followed by a distant Genya and Kyoji trudges to the young radical’s easel, where his painting of the Hokkaido snowscape rests (which then becomes animated itself) silently.

After the failure to find her love, Chikoyo returns to film, only to retire soon thereafter. Having lost her memento, the key, Chikoyo retires to seclusion. When the trio returns to the present, another earthquake hits, and Genya again throws himself over Chikoyo, though this time, he is not as successful. A dying Chikoyo is taken to the hospital, where she thanks Genya for bringing back the key and unlocking her beloved memories (and if anything, the film is a meditation on the nature of memory, how unreliable, yet wonderful it is, given how we conflate it with fantasy and strip it down into a cascade of images and sensations that is crafted into a sort of quasi-narrative). As Genya and Kyoji drive back to the city, a mournful Genya confesses that the government agent with the scar confided in him that he tortured the young artist to death during the war, but that he never told anyone that secret (though he told Chikoyo that she would finally find her love very soon). Back at the hospital, the elderly Chikoyo, breathing her last shallow breaths into an oxygen mask, transforms into the youthful Chikoyo, breathing in her space helmet, piloting her spaceship into the depths of space, happily declaring that it was the chase that always kept her going.

One last thing, I loved the animation. There is something to be said for traditional hand-drawn, two-dimensional animation (though the film does often use still drawings), even if they are animated at a slower frame rate than American animation. Some might find it quaint, and maybe I’m nostalgic, but I find a lot of recent American animation, most of which is done on computers now, to be artistically cookie-cutter. Here, you can see the artistry done in each frame. It’s quite simply amazing, and Satoshi Kon and his team of animators achieve spectacular results, in what is surely one of the most cinematic experiences I have had in a long, long time.

Thanks for the encouragement Phyrephox, maybe I’ll go to the next anime that is screening here in Madison,

Tamala 2010, even if does feature talking cats.