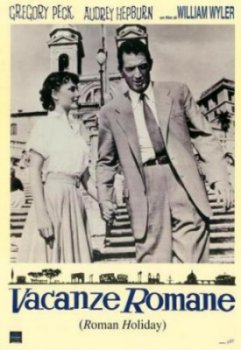

Roman Holiday

Roman Holiday, 1953. Directed by William Wyler, starring Gregory Peck, Audrey Hepburn and Eddie Albert.

Allyn posted a mini-rave about this film in mid-July, shortly after the passing of Gregory Peck. I've got nothing to challenge or disagree with Allyn about here – Roman Holiday is a movie I find to have few, if any, flaws, and one of the greatest three romance pictures ever captured on film. I've revisited it twice recently: once on the night of Peck's death, and again last night on the big screen at the Beverly Cinema in Hollywood.

Audrey Hepburn plays Princess Ann, direct heir to the throne of an unnamed country, on grueling European tour to improve trade relations. Cracking under the strain, she has a mild case of hysterics, and the doctor is called for to give her a sedative to make her sleep, and the following advice: "I think the best thing is to do just as you like for a little while."

It's advice she takes to heart. As the rest of the royal entourage goes off to sleep, she sneaks out of the palatial estate (hitching a ride on a laundry truck) and finds herself in the middle of Rome just as her sedative starts to kick in. Joe Bradley (Gregory Peck), an American newspaper man, happens upon her snoozing on a public bench, and does the chivalrous thing by taking her back to his place (strictly above board, of course – this is the fifties) and depositing her on his couch.

The next morning, the intrepid reporter figures out that he's got the biggest story in Rome sleeping on his couch, and enlists the aid of his photographer buddy Irving (Eddie Albert) to help him break the story. Together, the three embark on a holiday tour around Rome, doing just what "Anya" likes: getting her hair cut, her first cigarette, a wild romp on a Vespa, a tour of the Coliseum, the Wall of Wishes, the infamous Mouth of Truth, and a dance on a barge that ends in a free-for-all with some secret police from an undisclosed country.

There's one little catch, though – during their Roman holiday together, the newsman finds himself falling in love with his exclusive story, and the Princess with her duties to the throne finds herself feeling the exact same way. Both of them have been dishonest. Both of them are hiding something. And they both know it's hopeless. But they fall in love anyway. Now what?

I've seen a number of movies that play the 24-hour-romance angle, but Roman Holiday is the only one that I believe. It probably helps that Audrey Hepburn is absolutely captivating and Gregory Peck is at his most handsome and charming in this role – who wouldn't fall in love with either one of them?

The story was written by Dalton Trumbo, a member of the Hollywood Ten, when he was serving his prison sentence for contempt of Congress, and fronted by Ian McLellan Hunter (later blacklisted himself), who also got a screenwriting credit with John Dighton. It's probably the strongest story of Trumbo's career. For all his talents as a novelist (Johnny Got His Gun) and for all of his tireless efforts to break the blacklist (which he successfully did in 1960 when he gained his first screen credits in over ten years with Spartacus and Exodus), he wasn't all that good of a screenwriter, and he knew it. He was well-paid and well-known because he was fast (often cranking out a story a week), but his movies tend to be clichéd and clunky. The only other exception I can think of is Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, one of the smartest, best-scripted war films to come out of the World War II era.

In Allyn's review, he wrote: "I'm a fan of Audrey Hepburn, but I don't think she ever topped this performance -- she goes from weary princess, to drunk, to wide-eyed ingenue, to woman in love, to mature stateswoman in 24 hours." That sums it up pretty well. I was struck, in this most recent viewing, by how very young the Princess looks in her earlier scenes. She looks like she's about nineteen when the movie starts. By the end, she's matured immeasurably, and I don't think it's just the new hairstyle.

Peck has a tough role. Joe Bradley is really kind of a bastard through much of the film – he's using this woman to get a good story, and his ticket back to the states. But Peck makes him so likeable – and funny. Every time I see this movie I marvel at his flair for humor and wonder why he didn't make more comedies. At the same time, watch him at the moment that their romance begins to bloom, even as they both realize it will never be played out. You can practically hear his heart break.

If you take two beautiful people and costume them in Edith Head designs, put them in Rome and turn a camera on them, you've got a pretty decent movie right there. For some movies, that's even enough to coast on. To Catch a Thief is a good example -- looks great, but not a whole lot going on under the surface. Roman Holiday goes more than the extra mile, though. Beautifully restored and available on DVD. I'm hoping a 50th Anniversary print makes the rounds this year in theatres -- well worth seeing on the big screen.

Question of the Week

A couple of days ago, I saw an advertisement for the movie High Fidelity, and it inspired a new question of the week:

It's Top 5 List Time. What are the Top 5 Movies about.....Well, pick a subject and give us your Top 5 list. Also, give a short explanation of why these films belong on your list. Here's the catch. Once a subject has been used, you can not use it again. One other rule, do not pick a subject that is to broad; use your best judgement here.

This question is open to all blog members and readers, however, each respondent gets only one Top 5 List proper, but if you want to quibble with someone elses Top 5 list, feel free to come up with some alternatives.

Joker is Smarter Than Me....Plus My Review of Seabiscuit

Well, I saw several other films this weekend, but the only one that has not been reviewed so far is Gary Ross’s Seabiscuit. Why would I go to a film that just screams White Elephant Art? Well, simply put, I went because Seabiscuit stars three of my most favorite American screen actors: Tobey Maguire, Jeff Bridges, and Chris Cooper (I rarely go to films based solely on the actors, but I did so twice on Saturday; I also went to Pirates of the Caribbean solely to watch Johnny Depp’s performance). It’s not that I didn’t go in without some trepidation. I usually place White Elephant Art at the apex of my hierarchy of cinematic scorn, slightly above the Bay-Bruckheimer abominations, er, I mean collaborations. But sometimes, against my better judgment, I do, in fact, enjoy White Elephant Art (usually I’m either bored, i.e. Road to Perdition, or just plain angry at the film for wasting my time, i.e. The Hours). Seabiscuit definitely has it’s share of problems, the least of which is that it’s a big, soppy sentimental film, aided immeasurably in this regard by Randy Newman’s manipulative score (cue swelling strings, cue mournful horns).

However, the biggest problem with the film is that Gary Ross equates the story of Seabiscuit with that of America itself during the Great Depression, attempting to generate some sort of populist, liberal myth making (a la Capra, hell, you could stick Eddie Jones, who plays Mr. Riddle, the owner of Triple Crown winner War Admiral, in a wheelchair and call him Mr. Potter). When David McCullough began his narration over some iconic B&W still pictures (and there are plenty of those throughout the movie; it takes about an hour of backstory, unfolding over the course of 20-30 years, with every major historical turning point gratuitously highlighted, before Seabiscuit shows up), I thought that Ken Burns had kicked Gary Ross out of the director’s chair (this attempt at adding some historical gravitas is an exemplar of Ross’s trend of dropping anvils on the heads of the audience, just in case we miss the tropes of a Hollywood prestige picture). To be fair, I actually like some of Ross’s usage of these B&W stills: during the first race at Santa Anita, as the horses approach the finish line, Gary Ross suddenly fades to white, filling the soundtrack with disappointed groans, before fading back into a still picture of another horse beating Seabiscuit by a nose. The other usage of still pictures that I really like was during the first segment of the legendary race between Seabiscuit and War Admiral; Ross depicts this first segment solely through pictures of people huddled around their radios, as the crackle of a period radio broadcast describes the events on the soundtrack. I almost wish that Ross had continued to use the stills, instead he cuts back to the live action version of the race (which was not disappointing, I just wanted some more creative staging, for the most part, everything is safely staged, sometimes compelling so, but Ross takes few chances).

It’s unfortunate that Ross puts so much stock in his myth making, because his film works best as a portrait of wounded men, and a horse, coming together, helping each other, and forming an unlikely family (even with a surrogate mother-figure in Elizabeth Bank’s Marcela Howard, who does little but provide encouragement and look fetching in period garb). Gary Ross’s talents as a speech and comedy writer are put to good use with Jeff Bridge’s character, Charles Howard, the self-made millionaire car salesman who owns Seabiscuit. The perpetually optimistic Howard (save for the days following the death of his young son) has an uncanny knack for publicity, bullshitting, and populist rhetoric. In short, he’s the consummate car salesman, or politician. It’s through these speeches that Ross draws many of his parallels between the story of Seabiscuit and the Depression, with Howard’s talk of the future mirroring New Deal Optimism (pride and second chances figure largely in Howard’s speeches, often preceded or followed by a paean to the WPA, for instance, courtesy of David McCullough); at one point, Howard even delivers one of his speeches from the rear of a train, as if he was on some sort of political, whistle stop tour (in many ways it was).  Howard’s gregariousness is well-matched by Chris Cooper’s taciturn portrayal of Seabiscuit’s trainer, Tom Smith, an ex-cowboy, who was cast adrift when the frontier closed. Bridges might have the showier part, but I think that Cooper’s performance is much better, since he’s one of our best actors when it comes to roles that do not require much talk (thinking about it, it’s kind of ironic he won an Oscar for his role in Adaptation, since his character never really shuts up, it’s sort of an anomaly; I’ll be pulling for him again next year), the type of person who plays there cards close to their chest (he’s gruff, but sensitive). Tobey Maguire gives an assured performance in his role as the jockey with a chip on his shoulder, Red Pollard, but he also has the weakest character in the film, being saddled with a character arc infused with simplistic psychology (actually, Charles Howard’s grief over the death of his son is probably the most psychologically simplistic, since Red Pollard neatly slides into the role of the replacement son at a requisite point in the film), even if it based on fact; from what I’ve read in the many articles about the film and Laura Hillenbrand’s book, Red Pollard was a much more complex character, but his rougher edges (such as his alcoholism) were smoothed out by the screenplay. I also have to note that William H. Macy provides a hammy turn as a radio-announcer with a somewhat hilarious schtick, kind of like a 30s era gonzo radio personality, complete with a full repertoire of corny 30s slang and gimmicky toys.

Besides the acting, the other main strengths of the film are the racing sequences, which are very exciting to watch, you get right in the action, with the Tiajuana races being particularly brutal (all Buffy the Vampire Slayer fans should note that Danny Strong, aka Jonathan, has a small role as a jockey during this sequence); the beautiful cinematography and production design (something you can usually count on in all White Elephant Art); and a real historical story that would be hard to mess up (though they apparently did in the 1949 version, starring Shirley Temple). It’s just too bad that Ross can’t resist the temptation of inflating a compelling story with too much self-importance. Oh well, it should clean up at both the box office and the Oscars.

Chronicle of the Years of Embers/Chronique des années de braise (d. Mohamed Lakhdar-Hamina)

The winner of the Palm D’or in 1975, Chronicle of the Years of Embers is a 177 minute epic of Algerian cinema. I guess you could call the film something of a prequel to the more famous 1965 film The Battle of Algiers (though the perspective of the French troops and the pied noirs are largely absent), as it spans the years between 1939 and November 1st, 1954 (actually November 11th, if you count the epilogue), the day the Algerian Revolution began. Chronicle of the Years of Embers is one of those rare creatures, an uncompromising political film, which is not simply didactic, but is instead steeped in a quiet, affecting humanism, which just serves to underline the tragedy of the colonial system, the racism, the brutality, the degradation, the dehumanization, the humiliation, and the economic disparity. The film does so by centering on the character of Ahmad, a poor, yet proud, farmer who lives in a small village suffering from years of drought and colonial neglect (later, we actually learn that water is plentiful, if you are a French settler). The course of the film, which is divided into six chapters and an epilogue (with such titles as “The Years of Ashes,” “The Year of the Cart,” “The Year of the Massacre,” and “November 1st, 1954), charts the emerging revolutionary consciousness of Ahmad as tragedy after tragedy befalls his family and people; Ahmad does not become radicalized due to some overt political analysis, but for the practical reason of his and (his remaining) family’s survival. The other main character of the film is Miloud, the wild-haired madman who lives in the city where Ahmad eventually migrates (he’s played by writer-director Mohmaded Lakhdar-Hamina). Miloud is something of a Greek chorus, commenting on the action, openly mocking the French authority (he’s mad, so they pay him little attention), extolling the people to rise up and resist (though he preaches in the city’s many cemeteries). Eventually, Miloud befriends Ahmad, and becomes something of surrogate parent to Ahmad’s youngest son, especially once his father becomes more politically active (which leads to his imprisonment and armed resistance). By the film’s end, the situation has become so dire that even the French and their Arab puppets can not tolerate the dissent of an old, madman, (especially after he announces, like a town crier, the emergence of the revolution), and he is tortured. The formerly comic character becomes tragic, weakened, he dies alone in the cemetery lamenting his homeland’s lack of freedom.

But to back things up. As if to underline the desperation felt by the film’s characters, the story actually begins with a scene of local Arab tribesman violently fighting over a shallow pool of muddy water, a scene which ends tragically when a young man is shot dead. Immediately afterwards, the director, Mohamed Lakhdar-Hamina, shows the impact of the drought on the villagers, as one after another leaves the village, each time rushing through a gaggle of people imploring them to stay (ironically, each time the film cuts to another scene of a towns person leaving, it turns out to be one of the people who was trying to convince the others to stay). We first see Ahmad striding through the haze of the roiling heat (the film is shot in beautiful widescreen, color photography), as he comes across his eldest son crying, bent over the family's flock of sheep, which are slowly dying of dehydration, panting shallowly, tongues lolling from their mouth. Ahmad comforts his son, and eventually the two of them join the neighboring tribes people on a pilgrimage, led by the local cleric, to a shrine to pray for rain (complete with a very real sacrifice of a cow). Initially Ahmad is too proud to leave his village, despite the death of his sheep, and the long, long treks to retrieve water (in one of the film’s most gasp inducing early moments, his daughter, a toddler, unknowingly spills all the contents of a waterskin, that took several days of walking to fill; it’s a sad scene, as the baby girl smiles at her father, thinking she has helped, while everyone else in the house stares quietly, eventually Ahmad picks up his little girl, and their is an uncomfortable moment of silence, before he smiles and kisses his daughter, breaking the tension, but ultimately not dispelling the tragic dimension of what happened; I have to note, that Chronicle of the Years of Embers is a very quiet film, though it possesses somewhat melachonic, yet elegaic, score), but after a frustratingly brief rainstorm, followed by more blistering drought (we see the villager’s grain turn from vibrant green to a burnt out brown), Ahmad angrily relents and takes his family to a nearby provincial city, where one of his many cousins live.

There, Ahmad finds a job at a French-run salt mine, but his temper causes him to lash out at the cruel French overseer (on his first day, Ahmad sits down to eat lunch with his eldest son, and the Frenchman throws dirt all over his food and water, demanding that Ahmad return to work), which leads to a severe beating at the hands of the thuggish colonial police, while the sneering overseer, his eye blackened by Ahmad’s punch, looks on. The subsequent scene, where Miloud and Ahmad’s eldest son meet the battered man outside the police station is reminiscent of the famous, final scene from De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, with the utter humiliation of the proud father. To add to his humiliation, Ahmad is blacklisted by the local French employers, and finds himself out of work and idle. Though Ahmad spends most of his time in a fruitless search for work, he does manage to meet some friends and secretly listen to banned broadcasts of German propaganda, puffing on cigarettes, muttering about how the “French were finished,” thinking, ironically, that Hitler was some sort of savior. The defeat of the French and the installation of the Vichy puppet regime does little to change the everyday living conditions of the Arab population (though we do see a Vichy political rally, attended by the majority of the city’s French citizens, in front of a large picture of Marshall Petain; the pied noirs stretch out their arms in a Fascist salute to the French tricolor); later, as Ahmad and his fellow workers watch a convoy of American trucks drive through a wheat field, he remarks that “French, German, Americans, it doesn’t matter.”

Eventually, Ahmad’s cousin gets him a job in a wheat field (through bribery, of course), but tragedy quickly ensues, as his cousin faints in the fields, dying of fever, heralding an outbreak of typhus which ravages the city. The French authorities evacuate the French settlers (who number between 20-40) and seal the Arab population in a quarantine (the program notes at the screening remarks how this episode, entitled “The Year of the Cart,” after the wagons which hall the dead away, is almost an inverse of Camus’s The Plague, from the Arab perspective), enforced by Arab troops (everyone tries to flee through the ancient city gates, but they are forced back at gunpoint). In this, the film’s most harrowing section, Ahmad is forced to watch his entire extended family slowly die from fever, it seems that only Ahmad and the madman Miloud (who pushes a cart that collects the dead, and finds more and more people to preach to) are left untouched, witness to the devastation. Deserted by the French, the Arab population is left to fend for itself, with very little medicine (it seems like most of the government effort was concentrated on enforcing the quarantine and putting up anti-lice posters). For one extended sequence, Ahmad carries the limp body of his son throughout the twisting streets of the city, crossing paths with cart after cart of bodies, vainly looking for help. Brusquely told to go the church for “help,” he finds it to be a place where the very young and the very old are herded to die. Ahmad manages to pilfer a box of medicine, but it’s not enough. When he returns to his cousin’s house, what little medicine they have is not enough, and the members of the family begin to die one by one, signified by shots of the bodies being covered with sheets. By the end of the typhus outbreak, Ahmad is left alone, the only other survivor being his infant son. When the quarantine is finally lifted, Ahmad bundles his child up and leaves the city, returning to his home village. As he exits the city gates, he passes the truck carrying the French settlers back to their homes; the sing gayly, willfully oblivious to the horror around them.

Back home, Ahmad finds conditions have changed very little. He moves in with another of his cousins, and the desperate search for water continues. Drought still grips the countryside, though water is readily available; a huge reservoir stretches out to the horizon, created a French dam, but this water is only available for French crops, the Arab tribesmen left to scramble and fight over whatever trickle of water is released by the French. Soon the two local tribes are standing off at the end of a rifle, which disgusts Ahmad. In his first act of political (and practical) resistance, Ahmad leads five men from each tribe to the dam (Including his cousin), where they lay charges and blast a hole in the stone edifice, causing the dam to crumble, releasing the water. Though they are caught by the French, the men are still proud of what they did (Ahmad and one of the leaders from the other tribe smile proudly to each other, even when shackled and shaved bald by the French). As punishment, the 10 men are conscripted into the French Army, and forced to fight in Europe. Lakdhar-Hamina chooses to illustrate the war years with newsreel footage of the war, followed by celebrations of V-Day in Paris, and then more disturbing newsreel footage of the aftermath of an uprising in Algeria. It turns out, that on May 8th, the day the Germans surrendered, the French violently put down a countrywide uprising.

A uniformed Ahmad returns to his village alone, only to find it largely empty, recent fires still smoldering. Ahmad is greeted by the kindly old cleric, who informs him of what happened (the film, in a rare flashback, shows how the French herded the townspeople. attempting to “pacify” the region), and that his cousin’s family has fled to the city. Ahmad, wanting to be reunited with his son, follows suit. Even though he wears a French army uniform, festooned with a medal (later, a disgusted Ahmad throws this medal away, very reminiscent of Vietnam vets throwing away their own medals in protest; though, Miloud picks up the medal and pins it to his dusty robes), Ahmad is regarded with suspicion, and is even beaten when he steps out of line. When Ahmad reunites with his family, we learn that Ahmad is the only survivor of the 10 men sent to Europe. Needless to say, his cousin’s family does not take the news very well.

Quietly embittered (I must note that the actor who plays Ahmad has a wonderfully expressive face, often captured in close-up, which can go from kindness to seething rage in an instant), Ahmad goes to work as a blacksmith, along with an old friend from his village. The men like to sit around and gossip, grousing about the French, but doing little or nothing. That is, until a bespectacled Arab man, in a business suit and carrying a briefcase, arrives one day on the bus. Though his visits to the police station initially draws the suspicion of the local men, it’s soon learned that the man is named Larbi, and he is a political activist, exiled to the provinces by the French. Larbi is a radical nationalist, who advocates armed resistance (Larbi remarks that colonialism began with violence and will only end with violence), and it doesn’t take long for him to organize a group of followers among the disaffected locals, especially Ahmad, who, in his own stoic way, becomes something of his right hand man. Larbi’s position is not especially popular, at least, not yet, even splitting Ahmad’s friends (most of the nationalists follow a philosophy of accommodation, and resistance through elections), though you can tell that they are somewhat sympathetic (one man, in particular seems to continually waver, regretfully looking back everytime the two groups meet and then part).

Larbi’s activities (after questioning a imam’s interpretation of the Qu’ran that seems to support French rule) get him beaten up by the French agents sent to watch him, but that doesn’t dissuade him from continuing his struggle. Things come to a head when a Party leader visits the city advocating independence through elections; he wants to lead a rally to disrupt a speech by the local Arab strongman (known as the Caid), who acts as the French puppet. Larbi tries to convince him otherwise, but in a show of solidarity, joins the protest march along with his own followers. When the French get wind of the protest, they set an ambush. The impassive, uniformed French officers look on from a nearby balcony, as the protest march is trapped in a narrow roadway by the mounted calvary of the Caid. Snipers assassinate Larbi, shooting him in the head, and wound the Party candidate, before the calvary herded the hundred or so protesters into the square, where the Caid’s rally had previously been taking place. Encircling the protesters, herding them back into the square, letting none escape, the horseman, massacre the protesters with sabers and rifles (for the most part, this sequence is captured in a series of long and extreme long shots), as the townspeople who had been attending the rally look on from the rooftops. Some of the men, led by Ahmad and his group, attempt to fight back, knocking soldiers off their horses, stealing their sabers and guns. At first, it looks like the tide is turning against the Caid’s men, but just as quickly it turns back, until there are only eight survivors, bloody and battered, huddled underneath an archway, led by a still defiant Ahmad. The eight survivors of “The Year of the Massacre” are imprisoned for two years by the French rulers, but escape, becoming, as Miloud puts it, “phantoms of the resistance.” The guerilla movement has begun (underscored by a shot of the men blowing up a train).

With the situation in Algeria escalating, the French can not afford the increasing fame of Ahmad and his group, so they organize troops to hunt him down. Ahmad’s surviving son, now a young boy (about 10-12 years old), senses the danger, and convinces Miloud to lead him to his father. The two of them hike through the snowy, tree-covered mountains, but arrive too late. While resting in a sympathizer’s cabin, they hear the crackle of automatic weapons fire in the distance. The next day, Miloud and Ahmad’s son arrive at the guerilla encampment, only to find Ahmad dead, only a bloodstain on the cobblestones remain. He sacrificed himself to save the others (shown in flashback, and continuing a pattern, where Ahmad continues to fight and sacrifice, first for himself, and then for others), and the men pronounce him a hero of the resistance. A title announces that Ahmad died on November 1st, 1954.

In the film’s epilogue, we see that the revolution is already underway. This sequence is the most expressionistic of the film, as Lakhdar-Hamina cuts between three different sequences, as he builds up to his conclusion: the Caid torturing Miloud for preaching the revolution by tying him to his horse, and dragging him through the streets; Miloud dying in the cemetery, pleading to the dead, lamenting the plight of his country (since the part is played by the director, it’s not hard to draw the conclusion that these were his own feelings during that time period), while Ahmad’s son runs to his side (again, he’s ultimately too late), and a fantasy sequence which reintroduces the now deceased Ahmad. This sequence echoes Ahmad’s actual entrance in the film, we see him, now dressed in modern clothing, instead of the traditional garb he wore at the beginning, walking through the roiling heat, though this time, his son runs up to him in the distance. Without breaking a stride, Ahmad scoops his son up into his arms (something we never really saw him do in life). At the very end of the film, Ahmad’s son reaches Miloud in the cemetery, but it is too late, the old man has died. The son is now all alone, and must fight for himself. The films ends with a profile of Miloud’s bearded face against the setting sun. The film fades to black, as sounds of machine gun fire begin to fill the soundtrack. A final title announces the Algeria won it’s independence in 1962, but at a cost of one million lives.

|