The Tall T

The Cinematheque Budd Boetticher retrospective continued with perhaps the best known of the Randolph Scott-Budd Boetticher-Burt Kennedy Westerns, 1957’s

The Tall T. It is probably best known today because it is based on a story by the writer Elmore Leonard, who began his career in the 1950s by writing Western stories (that, and it wasn’t considered lost like the superior

Seven Men From Now). The film is both similar to the earlier film, in terms of it’s moral universe (the Ranown Cycle of Westerns are often credited with introducing moral and sexual ambiguity, as well as an marked increase in the brutality, to the genre, thus paving the way for the revisionist Westerns of the 1960s and 1970s by the likes of Leone, Peckinpah, and Eastwood) and some stylistic elements (much of the movie takes place in one setting, an encampment in the New Mexico wilderness, which includes a crude hut burrowed into the side of some rocky crags), again clocking in at a lean, mean 77 minutes, as well as maintaining the even, unhurried, professional, somewhat austere tone.

One of the crucial differences is in the initial characterization of Randolph Scott’s character, who, in this film, is named Pat Brennan. There are several reasons for this difference: well for one, unlike

Seven Men From Now,

The Tall T does not begin

in media res, and is much more upfront in the back story department, than the stingier

Seven Men From Now. There is roughly 15-20 minutes of exposition before the film launches into it’s main plot, and during that time, we learn a lot of the character of Pat Brennan. For one thing, he’s quite talkative and genial (at least at first), unlike the driven, stoic Ben Stride, even going as far as to buy some stick candy for the stationmaster’s son (which leads to some rather comic moments, because in the first part of the film, this big, burly cowboy is continually holding a bag of candy, prompting some rather bizarre looks from the townspeople). We also learn that Pat Brennan has recently bought himself a stake, near the Sassapeake Creek (which is near the copper-mining town of Contention, where the railroads are encroaching, threatening to put the local stage coach line out of business; though never seen in the film, railroads are often seen as a sign of progress in Westerns, encroaching civilization; it must be noted that Brennan lives entirely alone, far from town, in the wilderness), to the consternation of his former ranch boss, 10-40, because, as we learn, Brennan was the best “ramrod” in the territory. But it is also in this part of the movie, that Brennan loses his horse in a bet with 10-40 over a bull, thus necessitating Brennan joining up with the chartered stage coach, which drives the rest of the plot.

Like in

Seven Men From Now,

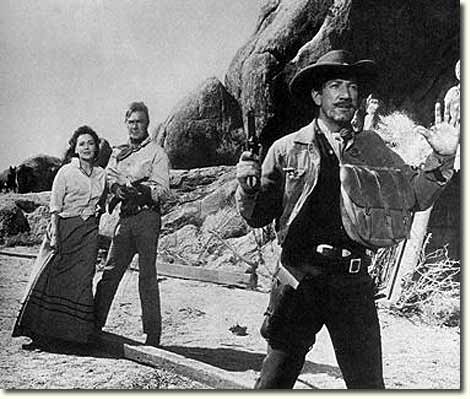

The Tall T, also sets up a triumvirate of masculinity similar to the Stride-Greer-Masters triangle of the former film. In Contention, we are introduced to the dandyish Willard Mims, an extremely nervous and talkative Easterner, who looks faintly ridiculous in his light blue suit, especially when compared with the rugged, dusty Brennan (the old codger who drives the stage coach, Rintoon, notes that he is an “accountant,” saying it with bemused contempt). The morning that the film begins, Willard Mims has married Doretta, the daughter of a local copper baron, played by a plain jane, well actually Jane herself, Maureen O’Sullivan. Everyone knows that Willard married her for the money, and that if it wasn’t for him, she would be on the road to being an “old maid.” And while everyone else seems to think of her as rather plain and marmish (she dresses like a schoolmarm IMO), Brennan thinks she is pretty. The third part of the triumvirate is met later in the film, Usher, the leader of the three bandits that hijack the Mim’s chartered stage coach (which is driven by Rintoon, and carries a horse-less Brennan). Usher is another dark doppleganger, like Ben Masters, though the film is less explicit in making that connection. Still, the two of them share a similar moral code and a wary respect for each other (Usher spares Brennan from execution because he likes him; that and their shared fear of loneliness, has led many writers to comment on the homoerotic undertones of these relationships, especially since Randolph Scott was a closeted homosexual); if it wasn’t for a bad-break in Wyoming (which is alluded to, but never explained), Usher could have been as successful as Brennan, with his own stake, and vice versa (the film earlier hinted at Brennan potential dark side when he punched-out his replacement at 10-40’s ranch, out of anger and wounded pride). Usher is actually fairly envious of the life that Brennan has made for himself (though he is never spiteful, at one point, he asks Brennan to ride with him).

Usher is the leader of a trio of bandits; he’s the relatively normal one, actually claiming to never have shot anyone (though he’s ordered more than a few deaths in his time). The other two pretty much psychopaths, taking pleasure in the pain and death they bring, though they are not very smart. Billy Jack is perhaps the dumbest, and ironically virginal, while the unfortunately named Chink (played by Henry Silva, who apparently played every evil Asian role in the 1950s and 1960s) is the expert with the guns, quick and lethal. Usher confesses to Brennan that he not only doesn’t trust Billy Jack and Chink (wonder why), but he doesn’t particularly like them. When asked by Brennan why he rides with them, he replies that he doesn’t want to be lonely.

Loneliness is a constant refrain in the film, almost from the start. When Brennan rides up to the way station, the stationmaster confesses that he is lonely out in the wilderness, and that being lonely is no way to live. Characters constantly remark that Brennan lives alone at his stake, and while Brennan seems to shrug it off, you can tell that the loneliness is starting to effect him also. Other major characters are motivated by loneliness also, including the before mentioned Usher, as well as Doretta. She knew that Mims married her for her father’s money, but she would rather have been married to a man who didn’t love her, than be alone. It’s interesting that much of the film takes place in a virtual wasteland, with barely anyone in sight (the film basically becomes a 5-6 person chamber piece once the film moves to it’s main setting), the wide expanse of land, emphasizing isolation, reflecting the character’s psychology.

The plot of the movie is fairly simple. When the stage coach arrives at the way station, Brennan and the Mims are captured (Rintoon is shot dead by Chink); it is at this point, that the Randolph Scott character becomes more like his earlier

Seven Men From Now incarnation, becoming more reserved, stoic, speaking only when necessary. Willard Mims on the other hand, becomes all blubbering, and in a bid to save his own life, confesses to Usher about his wife’s position, and the potential ransom. Willard’s actions earn contempt from both Usher and Brennan (as well as Doretta, once she finds out about his duplicity), but Usher agrees to go along with the plan, sending Billy Jack to accompany Mims back to Contention, to arrange the ransom (he is chaperoned because Usher doesn’t trust him to actually go into town and arrange the ransom; there is another great rhetorical question that is answered, when Mims asks Usher whether he is the sort of man who would sell out his wife, and Usher replies “Yes.”)

Usher and Chink take Brennan and Doretta back to their encampment to wait; knowing that certain death awaits him, even though Usher is letting him live, Brennan silently plots to keep himself and Doretta alive, as well as how to outwit the bandits, which isn’t that hard, considering the low IQs of Billy Jack and Chink. Usher is a different creature; in one of the more interesting moments of the film, Usher orders Chink to shoot the fleeing Mims in the back (this is after the arrangements for the ransom have been made; Usher just allows Mims the option of leaving; when the cowardly Mims does so, barely thinking of his wife, or Brennan, he seals his fate), Brennan protests (though not vehemently) noting that Usher went along with Mims’s plan. The angry Usher spits back “If you can’t see the difference, I ain’t explainin’.” And with Willard out of the way, Doretta begins to become smitten with Brennan.

The film is actually quite brutal for a film made in 1957. Just run through the litany of carnage that is the film:

*The kindly stationmaster and his young son (who is probably around 10) are brutally murdered, off-screen, their bodies unceremoniously dropped in the well.

*Rintoon goes for his gun, and is shot dead by a hidden Chink. As his body falls to the ground, Chink continues to fire, emptying his gun into Rintoon’s corpse. His body too, is dropped into the well.

*A fleeing Willard Mims is shot in the back with a rifle by Chink.

*After Usher and Chink go to collect the ransom, leaving Billy Jack to guard their prisoners, Brennan goads Billy Jack into entering the hut, telling him that both Usher and Chink have had their way with Doretta. It’s all a distraction, as Doretta, with her blouse unbuttoned acts seductively to keep Billy Jack’s attention away from Brennan. Then Brennan jumps Billy Jack and they struggle over a shot gun. It goes off, blowing Billy Jack’s head off. His body remains in a pool of blood for the rest of the movie (in Technicolor!)

*Brennan ambushes Chink, surprising and shooting him (he has Doretta discharge all six shots of her revolver, prompting Chink to come out of hiding). Chink spins around and falls to the ground, and attempts to crawl to another gun. Brennan continues to fire, shooting Chink in the back.

*After Usher returns to find Billy Jack and Chink dead, as well as an armed Brennan, he drops the ransom money and begins to walk away. Brennan warns him not to, but doesn’t try to stop him (this is actually a very tense, well directed scene, I half expected Brennan to plug Usher). Usher saddles up and begins to ride away, but after rounding a rocky bend, he pulls out a hidden rifle and charges back into camp. However, Brennan, expecting this, is ready, and shoots Usher in the face with a shotgun, putting out his eyes. A blinded Usher writhes in pain on the ground, blindly flailing for a weapon, before expiring in the dirt.

Of course, with everyone dead, except for Doretta and Brennan, the film ends on an ostensibly happy note, with the two of them embracing, walking off into the distance, presumably to ward off the plague of loneliness (everyone except for Doretta and Brennan who expressed thoughts about feeling lonely being dead) by living together at Brennan’s stake. All in all, the film was very good, but not as interesting as

Seven Men From Now, with a better drawn doppleganger (and let’s face it, Richard Boone is no Lee Marvin), tragic redemption (for Greer anyway), and less upbeat ending. Still,

The Tall T is an excellent Western, and I look forward to the continuing retrospective.

Elmore Leonard on The Tall T - The following is an excerpt from an interview with Leonard that appeared in

Film Comment (interview conducted by Patrick McGilligan, March-April 1998):

How About The Tall T

(57)?

That was a novella in

Argosy, which sold to Hollywood fairly quickly. I found out later that Batjac, John Wayne’s company had bought it originally, and then something happened and he passed it on to Randolph Scott and [producer] Harry Joe Brown. They also added about twenty minutes onto the front end, which I thought gave it an awfully slow opening.

And again you had nothing to do with the people in Hollywood who made the movie?

No. I saw that one in a screening room with Detroit newspaper critics. I remember the film coming to the part where Randolph Scott has Maureen O’Sullivan lure Skip Homeier into the cave. Randolph Scott comes in and faces Skip Homeier, who has a sawed-off shot gun in his hand. One of the critics said “Here comes the obligatory fistfight.” But Randolph Scott grabs the shotgun, sticks it under Skip Homeier’s chin, pulls the trigger, and the screen goes red [Shroomy’s note: I don’t remember the insertion of red frames, I’m pretty sure they cut to Doretta]. They didn’t say anything after that.

....

Did you get to meet Randolph Scott?

Yes, he came to Detroit to promote the picture and we were interviewed together for radio. I remember at the end he said to one of his aides, “Do you think I should wear my cowboy outfit to the theater premiere tonight?” I said, “No! God, no!” But he wasn’t asking me.

Did he look askance at you?

I think he did.