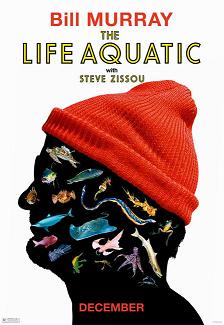

The Life Aquatic

Despite the title, as well as the aquatic professional focus of protagonist Steve Zissou (Billy Murray), Wes Anderson’s latest film is mostly about movie making. If Fellini’s

8½ was be some degrees more frivolous, deadpan, breezily rococo, and centered on Guido making a film about a shark as a stand-in for himself, it might look something like

The Life Aquatic.

Ostensibly the film follow Steve, a “documentary” aquatic adventure filmmaker, as he tries to rally Time Zissou to hunt down the mythical shark that killed his best friend during their last shoot. But like Fellini’s film before it, Steve has to wrestle more with the woes of production than actually capturing his subject in his film. Lack of funding, cheap equipment, his missing wife and muse (Angelica Houston) who has run off with Steve’s nemesis (Jeff Goldblum), the sudden appearance of Ned Plimpton (Owen Wilson), who may or may not be Zissou’s biological son, and a reporter with a bone to pick with the filmmaker’s slipping career (Cate Blanchett) coalesce into a whirl-wind crisis for Steve to put his life together by making this movie work.

Anderson’s wonderful kitsch-goofball vision is in full effect here, treading the line between

Rushmore’s unreserved lightweight atmosphere of solemnity and

The Royal Tenenbaum’s epically dense, implicitly grave humor. (The director and Noah Baumbach, who replaces Owen Wilson as Anderson’s usual co-writer, crafted the script.) The feeling of frivolity throughout the film, contributed to by an air of off-the-cuffness to the jokes, the strange tangibility of Anderson’s blend of borderline fantasy misé

-en-scene and the lovely Italian locations, and swerving visual and narrative digressions, thankfully make the film feel significantly less self-consciously grand as

The Royal Tenenbaums.

The self-reflexivity of Anderson’s showy technique is still here—this is a movie about making a movie after all—but the sepulchral, hyper-meticulousness of his previous film is here opened up with the wide coastal and oceanic setting. Spaces—like a wildly unkempt abandoned, monsoon-wrecked island resort, and Steve’s boat the Belafonte—feel more organic and explorable, and Anderson is notably less confined by his own design. The constant deprecating jesting amongst Team Zissou—most humor not streaming from a delightfully wry Murray is remarkably sprung from Willem Dafoe, who plays a German crewman whose status as surrogate son is usurped by Plimpton—the quaintly animated sea creatures (which look like an exotic aquarium gone claymation), and Anderson’s highly mobile, skimming camera, which often notably travels alongside a cross-section of the Belafonte alive and active as if it were multistory apartment building full of tenants, often produces an air of tomfoolery and spontaneity. It is as if Anderson and team, finding themselves inspired by their neo-kitsch production design of Adidas sneakers, pastel uniforms, Cousteau references and sudden dramatic and visual quaintness, sort of made up a story as they went along (much like Steve in his own film).

This humorous and generally invigorating atmosphere of fresh frivolity is moderately tempered by the film’s inability to depict Steve’s life crisis as one of emotion. Zissou is, by his own admission, a “prick” and chokes up or honestly expresses himself on rare occasion, and Owen’s actorly history makes one ignore his emotional blankness thankfully because he opted for the decidedly non-dufus straight man role of a Kentuckian airline pilot, but

someone in this film needs to carry its heart. Though not the protagonist in any sense, it is only Cate Blanchett’s gloriously individual performance as the pregnant, unstable reporter onboard the Belafonte who effectively communicates the bewildering emotional distress of one personally confused and looking for either an output in their impassioned work or help from the people involved in their work. This is certainly what

The Life Aquatic is about, the constant presence of the crew’s movie camera, and Zissou’s own movies looking like mini-Anderson shorts of goofy meticulous construction all indicate that this film itself is Zissou’s final product, a testament to a lost man (and his similarly searching co-workers) both finding his work in his life, and most importantly finding his life in his work. If only Murray or Anderson could have made the process of creation one that was ultimately moving rather than “just” an inventively fun watch

The Life Aquatic's ode to the importance of artistic creation out through the support structure of friends, co-workers, and family could have been a lightly touching one.