Question of the Week

Although the revenge film has never really faded in popularity, it seems that this Spring is full of them.

The Punisher goes on a vendetta when his family is massacred; The Bride seeks vengence for the destruction of her new life in

Kill Bill; Denzel razes Mexico because a young girl is abducted in

Man on Fire, etc. Even in films that aren't strictly revenge narratives the motif of individual vengence/vendetta is constantly rearing its head: Nicole Kidman is slapped down again and again until she simply has to do something about it in

Dogville, and similar themes can be found in

Spartan,

Elephant and several other art house and mainstream films released within the last year. What they have in common are themes of individuals seperating themselves from the community to take on personal vendettas. This inspires my question of the week:

What isyour favorite tale of bloody revenge?

And on a more sociaoogical note, why do you think the revenge film is making a sudden come-back in the world cinema and specifically in American cinema?

As usual, this question is open to all Milk Plus members and readers. Feel free to answer the question as many times as you wish, but I ask that you do not duplicate answers, though feel free to discuss other's choices and explanations.

Short Takes

I go through phases where sometimes I do not watch any actual movies on DVD for a long, long time. Perhaps motivated by the rapidly declining number of television shows that I regularly watch, I find myself entering a new, more active viewing phase. I even joined the DVD rental service

GreenCine last week. I got my first three DVDs over the weekend (plus, I managed to watch one of my favorites films,

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, though I so realized that I need to upgrade from VHS to DVD on that one):

Flesh + Blood (d. Paul Verhoeven 1985) - The recently released "Director’s Cut" of Paul Verhoeven's first American film (well actually, an American/European co-production) was the first DVD I watched. I'd call it a transitional work or something like that, but I've managed to have never seen any of Verhoeven's Dutch work, despite my love for his Hollywood output. It's a very bizarre movie to have originated from a Hollywood studio in the 1980s: dark, brutal, grim, completely full of unsympathetic characters, or, as Verhoeven puts it himself in the audio commentary, an "apocalyptic" movie (though I can not hope to replicate the unique way he pronounces the word with his thick Dutch accent). Set in war-torn, early 16th century Europe,

Flesh + Blood is centered around a love-triangle of sorts.

Rutger Hauer plays a mercenary named Martin, who after being betrayed and banished by an oily aristocrat named Arnolfini, leads a group of fellow mercenaries and camp followers in a pseudo-religious mission of killing, whoring, drinking, plundering, and vengeance. Vengeance is taken in the form of an ambush, which results in the kidnapping of the Agnes, the virginal fiancee of Arnolfini’s intellectual son Steven. Agnes, played by a youthful Jennifer Jason Leigh, is the ultimate survivor; after being captured by Martin's band, she literally throws herself at Martin, despite have been raped by him, manipulating him sexually into giving her protection and a more privileged position within the group, all the while encouraging the pursuing Steven, whose initial idealism and disgust for his father's actions is quickly discarded in favor of abusive, aristocratic privilege. Hmm, which ambiguous character to support, the psychopathic, rapist anti-hero? The charming, yet manipulative noblewoman, who ironically has feelings for both men, but puts herself above all? Or perhaps, the aristocratic prig? Yeah, that's a tough one.

Shot in Spain, with appropriately earthy photography by DP Jan de Bont, Verhoeven creates a violent, plague-ridden world on the precipice between the past and modernity (one major point of contrast between the characters is that Martin is motivated by a sort of misplaced religious fervor, though he more or less uses it to manipulate the rest of his merry band, whereas Steven is a scientist and rationalist who admires Da Vinci; other examples include the usage of guns versus swords; supernatural beliefs, especially medicinal, versus newer Arab knowledge; biological warfare, etc.). It's clearly not among the best Verhoeven film out there, but it was very interesting, at times outrageously cynical, setting the stage for the extreme nudity and violence of his later work (I personally enjoyed the

Greed-inspired love scene between Steven and Agnes set under the rotting corpses of some hung men). It's a rather unique worldview, something that was much needed in American films of the time (I also found it interesting, that despite all the flack that Verhoeven got for

Basic Instinct, the most sympathetic characters in the entire film are a gay couple).

By the way, while doing my laundry and listening to the audio commentary, replete with philosophical, religious, and historical references, I was wondering if the success of

The Passion of the Christ would encourage the greenlighting of Verhoeven's own films about Jesus Christ or the Crusades. Now that would be an interesting Jesus film.

Black Mail Is My Life (d. Kinji Fukasaku, 1968) - Basically got this film because I'm a big fan of Fukasaku's

Battle Royale, though this film, a dark, but rather jazzy, criminal thriller obsessed with memory (here represented by multiple flashbacks, voice-over narration, and still photomontages), is very different. Shun, the leader of an enterprising troupe of criminals, stages elaborate blackmailing schemes, gaining him both wealth and women, that is, until he tries to blackmail a highly-placed political boss, which leads to death and disaster. I guess the characters being defeated by an all powerful political regime is the common thread between

Battle Royale and

Black Mail is My Life (though the film created in the 1960s is much less hopeful). What I really liked about the film, and films like this, is the way that Fukasaku took the camera out onto the streets, capturing many shots of everyday Japanese urban life, much like their 60s New Wave counterparts in various European and Asian countries.

Barbarella (d. Roger Vadim, 1968) - Hmm, this campy sci-fi, where to start...Hmmm...Jane Fonda (complete with the Brigitte Bardot inspired hair) is really, really, really hot....uh, its weird....i liked the spaceships shag interior. Yeah, that’s about it. No, not really, actually it was kind of enjoyable, more as a late 60s time capsule than anything. Though, every time they said "Duran Duran" the song "Rio" popped into my head.

Also, besides

Kill Bill Vol. 2, I also saw the documentary

My Architect: A Son's Journey on Sunday afternoon (basically I had to run there after

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg). I really liked it, despite the fact that I didn't know much more about architect Louis Kahn after watching the documentary then I did going into it; but that was kind of the point. It's kind of like

Citizen Kane, everyone had rather positive things to say about Kahn (they made great allowances for this artistic genius, because sometimes he actually sounded more like a bastard), but nobody really knew him, just like his neglected son Nathaniel, whose quest to get to know his long deceased father is the motivation for the documentaries creation. Though he really doesn't learn anything concrete about his father, he does manage to visit all of his father's creations. Those sequences of the film, as the camera lingers on Kahn's monumentally beautiful achievements, were the best parts of the film. Makes me want to visit them myself and just wander around, because, as one Bangladeshi architect puts it, ten minutes captured on film is just not enough.

Well, my wrists are really sore today, and

Scrubs and

The Shield are on in short order, so I'm signing off for now. Talk to you guys later (waiting for

Touch of Zen to arrive in the mail later this week).

Bruno Dumont’s

Twentynine Palms marks a sad departure for a director whose previous two films devoted so much fascination to the human face. Maybe this move away from the often-spiritual resonance of the striking non-actors Dumont directed in

The Life of Jesus and

L’Humanité-faces that in far too many scenes proved more interesting than the films themselves-is reflected in the immense spatial jump Dumont takes with his latest film. He abandons the ghostly country town that he had previously shot his films in and, in a rather radical move, sets

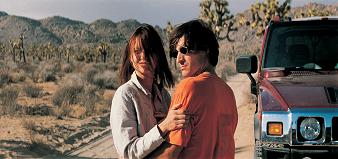

Twentynine Palms in the deserts of Southern California, of all places. Ostensibly in the middle of nowhere to “scout” locations, David (David Wissack) has taken his French girlfriend Katia (Katia Golubeva) along with him on a voyage that at first seems like a road trip with an end destination-the town of the film’s title-but eventually the repetition of a motel room clarifies that the couple is instead staying in Twentynine Palms and exploring the surrounding wilderness and their relationship to one another at their leisure.

Dumont drops David and Katia in

a ridiculous red Hummer and isolates them from the world outside, and despite frequent pit stops to view the scenery they couple only really fight and screw in civilization. They engage few of the humans around them-talking only to order food and even then having trouble communicating-and they form a pattern of awkward and usually pointless dialog sometimes spoken in French, which David only partially understands. Dumont’s use of dominant landscape, reticent dialog, and polar character reactions is typically glacial in its pacing and slowly accumulative in its meaning; it is not until well into the film that it becomes clear how different David and Katia are. Katia, who often professes her strong feelings for David and calls him “my love,” is gradually coded as the romantic of the couple with near-manic depressive outbursts of sudden weeping, laughing, and anger. David, like the audience, is simply mystified by Katia’s contradictory behavior and conversations, but he is no peach either, and his distant behavior is not

sympathetic.

Dumont’s expansive widescreen compositions not only physically separate the couple from the rest of humanity, but also separate the way the characters react to the landscape. Katia remarks on its beauty, while David gazes on with little understanding. With such a plotless narrative all of

Twentynine Palms small events assume tremendous importance-that Katia does not know how to drive and cannot seem to navigate the Hummer through the wildness is in paramount contrast to David who almost goes ballistic when Katia’s driving scratches the side of the Hummer on shrubbery. David is more utilitarian, a characteristic apparent in his lack of response to Katia’s professions of love for him and questions of love for her. Dumont is always very, very ambiguous about his relationships, for while David and Katia seems honestly in love with each other, he is always approaching her for sex-which is rough and physically one sided-while she is always giving emotionally one-sided proclamations of love. In a bleak landscape where little happens the trivial fights the couple has gets blown out of proportion, and the only other thing to do is partake in awkward, primal sex, which usually concludes with David releasing a horrendous banshee scream that seems to hold little pleasure.

It is these moments of intercourse that are the most telling of

Twentynine Palms' obtuse philosophy. David and Katia only engage in the activity in spaces of false nature-in the motel pool and in their hotel room beneath a picturesque image of snowy mountains-and the one time they attempt to have sex in the desert they come up dry (pun intended) and impotent. The disconnection with the natural world around them is key to the film’s gradual exposition that between these two people there is something deeply wrong with their understanding of each other and the world around them.

Unlike his last two films,

Twentynine Palms is free of any kind of spiritual transcendence; if anything, his last two films, which both ended “badly,” nevertheless revealed spiritualism in their protagonists, one that was integral to their supposed transcendence of their flaws-Dumont never made a particularly convincing argument on this point. That neither Wissack nor Golubeva distinctly share the ambiguous humanism evident in the faces of Dumont’s other films-with Wissack looking like a recovering burnt out 80s rock star only Golubeva’s sharp blues eyes and attractively wide smile push her visually closer to Dumont’s previous protagonists-may or may not a decision intended by Dumont. Certainly the film’s hyper-pessimistic ending points at either the decisive lack of spiritualism in the characters, or perhaps their loss of it throughout the film.

Even though this is the first Dumont film that takes on two protagonists (ostensibly Adam and Eve) instead of having a lead male and his marginalized love interest ,

Twentynine Palms

Twentynine Palms is no more dynamic or alive than his usual near-inexplicable art house tedium. Dumont’s use of composition may be sharp but like his narrative his mise-en-scene is limp and ineffectual aside for a handful of key moments, and again his film features characters who are impossible to begin to understand. Katia’s inability to communicate seems well balanced by her compassion and appreciation of nature but her reasons for staying with or even loving David is a mystery. Like the rest of Dumont’s films, a relatively lovely young girl is paired up with a man of questionable qualities.

Dumont’s narrative punishes both characters by this point, slapping them down for some obscure reason. The deep irony that Katia fawns over nature, but David, who has a profession involving finding and appreciating locations, fails to engage the world around him is key to the reason why he ends up being the one who cannot reconcile what he learns by the film’s end. At first it appears that both achieve a realization of the reality of their relationship, but, like the ideas that drive the film as a whole, this realization is neither completely understood nor results in growth for the couple-or the audience for that matter.

Twentynine Palms places a responsibility for comprehension on its characters that, as a united couple, they simply cannot handle, and likewise Dumont’s glacial pacing and arch-arthouse cinematic style tests the audience by making many moments of viewing a film a true chore. Just like

The Life of Jesus and

L’Humanité, gradually piecing Dumont’s latest film together can be fruitful and quite often the film is marvelous to watch, but the unending duration of the time one has to put into it and the “experimental” obtuseness of Dumont’s philosophy-inspired method makes it very difficult to recommend.

Young Adam

A life of loneliness and nihilism is hell, but in

Young Adam it at least is a stylish hell. The upside to such a life-one led by young, quasi-anonymous Scottish gadabout Joe (Ewan McGregor)-is that every object seems to burn with a subtle fetishism. The dreary canals of Glasgow with their rippling waterways, creeping darkness, and the just barely hidden beauty of every Scottishlass that hangs round the docks are pervasive with barely muffled sexuality. In view of the lethargy in Joe’s nihilism he seems to taint everything he does with grey romanticism. To this end he screws every woman in sight and yearningly sucks down hundreds of cigarettes all steeped in in the navy-dulled hues of the Scottish canal system. Even the nonchalant 1950s setting feels subtly textured and rife with minor sexual

details. As it should, I suppose, in a tale extrapolated from the classic noir

The Postman Always Rings Twice. No Venetian blinds or femme fatales here though; Joe haplessly seems drawn to lonely women in need of a good romp in the hay, and because most of them are permanently attached to their husbands Joe finds little threat of masculine usurpance in the constant beddings.

Elle (Tilda Swinton) for instance, is literally adrift in the tedious combination of barge-life and married-life, and her apparently impotent husband Les (Peter Mullan) has the unknowing bad luck of hiring sexual firebird Joe as a helper on their claustrophobic barge. Later we can chalk up several other similar and unusually attractive women to Joe’s list of hollow sexual conquests, chief among them a fling from the past, Cathie (Emily Mortimer), who almost…almost inspires some sort of human emotion in the introverted romantic that McGregor handsomely plays so well. (Hey, at least his slow-burning noir non-entity is a change from his previous entries as dandy romantics in

Down With Love and

Moulin Rouge!.) David Mckenzie’s script, which he not only adapted from Alexander Trocchi’s novel but also directs, is short on dialog and long on atmosphere. Unlike

The Postman Always Rings Twice our sleazy hero has no trouble seducing his Scottish ladies and much of

Young Adam's narrative tension dissipates after Swinton goes to bed with him in the first fifteen minutes. A similar disappointment erupts when the mystery of a floating corpse is used as a picture into Joe’s deplorable

oscillation between borderline humanity and anonymous nihilism rather than kicking up the dreary tension inherent in the film’s content.

At least the atmosphere comes in droves, and the rampant sexual activity of the cast cannot be complained about when they are as attractive as Swinton, McGregor, and Mortimer. There certainly are things churning lugubriously beneath the murky surface of

Young Adam; a handful of primal scenes and the stark contrast between Swinton’s gangly, domesticated beauty and Mortimer’s more youthful and kinky appeal speaks to lightly touched upon Freudian gestations in Joe’s melancholy drifting. Nothing is much developed, and the film always feels just too slow burning for its own good. By the third or fourth fling Joe has one begins to wish someone-anyone- would take another fatal dive in the canal to give the bountiful atmosphere some legitimate fatal justification. Still, Mckenzie has a keen visual sense. He somehow completely and effectively stylizes

Young Adam without it ever being overt; a quick glance at the film and it looks like a kitchen sink drama. A closer eye notices that the attention to dulled color and subtle lower-class texture of that genre is slyly transposed to noir styling. More effort is put into the film’s look than anything else and its imagery makes

Young Adam more of a laidback visual pleasure than a stimulating, or thrilling character study.