|

Joker Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-House of Flying Daggers

-The Aviator

-Bad Education

|

|

Yun-Fat Recommends

|

|

-Eight Diagram Pole Fighter

-Los Muertos

-Tropical Malady

|

|

Allyn Recommends

|

|

-Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

-Songs from the Second Floor

|

|

Phyrephox Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-Design for Living (Lubitsch, 1933)

-War of the Worlds

-Howl's Moving Castle

|

|

Melisb Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-The Return

-Spirited Away

-Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter...And Spring

|

|

Wardpet Recommends

|

|

-Finding Nemo

-Man on the Train

-28 Days Later

|

|

Lorne Recommends

|

|

-21 Grams

-Cold Mountain

-Lost in Translation

|

|

Merlot Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-The Man on the Train

-Safe Conduct

-The Statement

|

|

Whitney Recommends

|

|

-Femme Fatale

-Gangs of New York

-Grand Illusion

|

|

Sydhe Recommends

|

|

-In America

-Looney Tunes: Back In Action

-Whale Rider

|

|

Copywright Recommends

|

Top 20 List

-Flowers of Shanghai

-Road to Perdition

-Topsy-Turvy

|

|

Stennie Recommends

|

Top 20 List

-A Matter of Life and Death

-Ossessione

-Sideways

|

|

Jeff Recommends

|

|

-Dial M for Murder

-The Game

-Star Wars Saga

|

|

Lady Wakasa Recommends

|

|

-Dracula: Page from a Virgin's Diary

-Dr. Mabuse, Der Spieler

-The Last Laugh

|

|

Steve Recommends

|

-Top 20 List

-Princess Raccoon

-Princess Raccoon

-Princess Raccoon

|

|

Jenny Recommends

|

|

-Mean Girls

-Super Size Me

-The Warriors

|

|

Lons Recommends

|

|

-Before Sunset

-The Incredibles

-Sideways

|

|

(c)2002 Design by Blogscapes.com

|

The Blog:

|

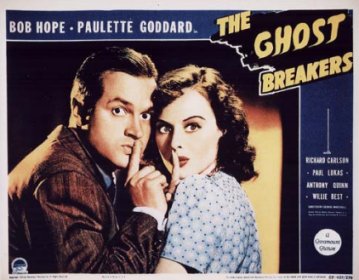

The Ghost Breakers

UCLA Film & Television Archive presented The Ghost Breakers last night as part of its "Archive Treasures" series. As they explain it: "Archive Treasures, sponsored by the Ted Mann Foundation, is dedicated to recreating the classic 'night at the movies' that drew peak audiences during the heyday of the Hollywood era. Each program will team newsreels and shorts with choice selections from the vaults of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and present original and restored prints in their full glory on the silver screen the way they were meant to be seen."

A fun idea, and I'm really glad I went. The evening started with a Warner Bros. cartoon short, "Malibu Beach Party," in which "Jack Bunny" invites the Hollywood elite to his Malibu home for a party. Hollywood stars with cartoon cameos included Jack Benny's wife Mary Livingstone (pictured), Bob Hope, Bette Davis, Claudette Colbert, Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, Fred MacMurray, Cesar Romero, Mickey Rooney, Astaire & Rogers, and lots more -- some of them I didn't recognize.

After the cartoon was a short subject called "London Can Take It," depicting life in London during the blitz, narrated by war correspondent Quentin Reynolds. Presented with no musical score, and in fact no sound at all except the sounds of the planes and the bombs, and Reynolds's quiet narration, it was a very moving portrayal of courage, and I'd imagine very effective propaganda in 1940 when it was first shown.

Then a newsreel, also all about the war in Europe, which then segued into a review of the US troops and their superior Navy and air forces, which elicited a grim chuckle from those of us who knew what was coming just a year or so later for that American Navy.

And then the main feature – the Bob Hope/Paulette Goddard horror-comedy spoof The Ghost Breakers. The print was not as good as I was expecting -- there was a line down the middle of the picture the entire time, and lots of missing frames which could be quite jarring, and one or two scenes were pretty spotty. But I'm not a huge quality hound anyway, as long as it's in focus and I can hear it, I'm usually happy enough as long as the movie is good.

And the movie IS good. This is probably my favorite Bob Hope movie so far, just edging out The Lemon Drop Kid and Sorrowful Jones. In the Road movies, and in fact in most of Hope's comedies, he has a habit of dropping in-jokes and breaking the fourth wall -- sometimes it's funny, but after watching about four or five of his movies earlier this year I found myself wishing he would just play a character straight for a change -- he might actually be a pretty good actor if he did. The Ghost Breakers is one of the few movies where he does just that -- plays the role straight, no relying on jokes about Paramount, Crosby or Pepsodent (his radio sponsor) to get by.

Paulette Goddard is Mary Carter, a woman who has inherited a haunted castle in Cuba. She doesn't believe in the ghosts that haunt it, and she ignores death threats and handsome offers of remuneration -- she's determined to go to Cuba to see her castle. Hope is Lawrence Lawrence Lawrence ("my folks had no imagination" – he goes by Larry Lawrence), a radio gossip columnist who, through a series of improbable mishaps, believes he has murdered a man and is trying to beat a hasty retreat. He ends up going to Cuba with her (as part of her luggage), and when he starts to get the feeling she is in danger, assigns himself as her protector and official "Ghost Breaker."

Almost all the best lines go to Alex, Hope's manservant (Willie Best), who does an awesome job with the material, despite the fact that Alex is portrayed with all of the racial stereotyping of the time.

There were not a lot of laugh-out-loud moments, which surprised me. It turned out to be a pretty effective blend of light comedy, thriller and mystery. Aside from most of Alex's lines, the biggest laughs of the evening came from an accordion-folded travel brochure, and Hope's and Goddard's failed attempts to read about the "flashing-eyed senoritas" of Cuba. LARRY: "Flashing-eyed senoritas" (turns page) "-- with red peppers and spices..." Is that legal? (He refolds the brochure and tries again) "Flashing-eyed senoritas" (turns page again) "-- spread out Continental style over the sidewalk."

MARY: (takes the brochure, refolds it) "Here we go. Flashing-eyed senoritas" (turns page) " -- equipped with red and green flashing lights to control the traffic." Also this little throw-away line drew a surprisingly positive reaction for a UCLA crowd: JEFF: "Zombies have no will of their own. You see them walking around with dead eyes, following orders, not knowing what they do, not caring."

LARRY: "You mean like Democrats?" Hope was good and very consistent, Goddard was stunning and beautiful as usual. Anthony Quinn was menacing in his role of "the heavy." The pacing was quick but not forced. A delicate balance is required here – comedy goes fast and thrillers take their time. George Marshall did an admirable job of blending both, although I did find myself wishing they would get to the castle already.

There were a couple of things I didn't get, like who was the zombie and what was he doing there in the first place, for example, but overall, a fun night at the movies for Halloween.

For anyone in the L.A. area, there are a lot of good movies coming up this month at UCLA, including a month-long tribute to Frank Borzage, and five days of Erroll Morris – which I can't find on the damn schedule, unfortunately. Check out the schedule here.

Milk Plus: A Discussion of Television

Well, I've reviewed an episode of Alias and a Volvo Commercial; and Joker has reviewed the World Cup, one of the Nike Shox commercials and The Shield S1 DVD set, so television is definitely not a taboo topic for discussion on this board. However, I thought I would experiment with a little bit of a new format by creating this post so anyone could be free to discuss the various television shows that we all know and love (for me that would be Alias, 24, MI-5, Angel, and Scrubs), or hate, as the case maybe. I figure it would be easier than writing individual episode reviews for the various TV shows. Feel free to discuss any TV show, TV mini-series, TV movie, or commercial in the comments of this post; don't fret, if you want to post to the main board about a TV-related topic, feel free. If interest warrants, I'll periodically introduce new posts to further our discussion. Have fun.

Cannibal Holocaust

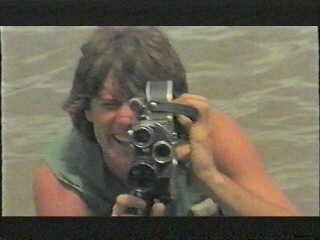

Well, I finally saw this film on Thursday, after a month of eager anticipation. I had been curious to see this notorious film since it resurfaced in the wake of the Blair Witch Project’s release. It’s another one of those films, like Battle Royale, whose reputation precedes it, stoked by the controversy surrounding it’s release, as well as on-line rumor and half-rememberd midnight screenings. Let’s just say that I was taken aback by what I actually saw, as I thought I was going to see a more realistic, yet still over the top, exploitation bloodbath. What was most surprising was that a film called Cannibal Holocaust, supposedly the pinnacle film of the Italian cannibal genre (I have not seen any other examples of this genre, so I’m forced to go on hearsay), had such an intellectual contempt for its’s audience, though it still delivers the mondo thrills to anyone who would find such material “entertaining”. Through their film, director Ruggero Deodato and writer Gianfranco Clerici, outright condemns anyone who would want to watch such footage for entertainment purposes (to the point of half-heartedly operating under the pretense that the footage is real, just to hook in the curious) , while also critiquing the idea of documentary responsibility through the actions of the “victimized” documentary film-crew (all Americans from NYC, three men and one woman), who are more like Robert Flaherty-as-Satan than intrepid explorers.

First, to clear up some popular misconceptions about the film. It really is not all that gory, though what is shown is done so in a fairly realistic way (in fact, several animals which were depicted as being slaughtered in the film, were killed in reality); much of the actual mutilation, dismemberment, and cannibalism is shown, for the most part, from a distance, in bouncy, obscured, often out of focus shots. What is most stomach churning about the film is the extremely graphic, brutally realistic scenes of sexual violence against women (these scenes shut up the giggling stoners in the audience right away); the film includes a trio of rape scenes, as well as displaying the aftermath of sexual torture against a native woman (who may or may not have been the same native woman that the male members of the documentary crew gang raped in an earlier scene, I could not tell), who is shown skewered on a pole.

Secondly, the film is not compromised of all found footage, as was implied when people used the example of Cannibal Holocaust to debunk the Blair Witch Project rather novel stylistic approach. We are initially introduced to the four American filmmakers, as well as their jungle guide, via a television news report, which segues into an American interview show. It seems that the filmmakers had been missing for some time now, and NYU anthropology professor, Dr. Harold Monroe (Robert Kerman, who apparently starred in several cannibal films, as well as many pornos) is leading an expedition into Amazonia (or as the film typically refers to jungle, “the green inferno”) to find out what happened. The first half of the film is a fairly stylistically standard film, as Monroe is led into the jungle by his two guides, as well as a captive native from one of the more peaceful tribes. Signs of the initial expeditions disaster are every where (the worm-infested skeletal remains of the guide Felipe, natives wearing Western trinkets and practicing ritual cannibalism to drive out evil spirits, a burned out village full of fearful natives) but it is not until Monroe meets and befriends the cannibal tribe known as the Tree People that he finds what remains of the film crew: bones, tattered clothing, and film equipment. Monroe bargains with the Tree People Chieftain, who thinks Monroe is a powerful sorcerer because of his tape recorder, for the remaining film canisters, which hang as decoration in the Tree People village, and then seals the deal by partaking in a little human flesh.

From there, the film returns to New York City, where Monroe is in negotiations with some network executives to turn the found footage, which has yet to be processed or screened, into a potential television documentary. From there, Monroe’s positive preconceptions about the filmmakers, led by director Alan Yates, begins to unravel; first, through some man-on-the-street interviews with the filmmakers surviving relatives, many of whom have mixed feelings, to say the least, about their dearly departed, and then during a screening of one of Yates’s earlier films, a documentary about revolution in Africa. We learn from a nonplussed network executive that Yates typically staged the outlandish or violent scenes in his films, in this case, hiring soldiers to execute civilians as rebels (thus the film again blurs the boundaries between fiction and documentary). Then the screening of the found footage begins (some of which is silent). We see the television interviews which opened the film from the perspective of the filmmakers own hand-held cameras, and begin to see a more detailed picture of the filmmakers: cocky, arrogant, assholes, who would just as soon point a gun at somebody as they would a camera. In fact, a lot of their hijincks makes the trio of men come off like a bunch of out of control, horny frat boys. The footage, which is often overlaid with the film’s late 70s synth soundtrack (which comes in two varieties, incongruously mellow and portentous), becomes progressively more disturbing, as the filmmakers seem to document just about every step of their journey. Disaster first strikes when their guide puts on his boots and is bitten by a poisonous snake; the filmmakers attempt to save his life by amputating his leg (in close-up) with a machete, but they fail, and the filmmakers press on.

When they reach the first native village, they use their rifles to scare the natives, shooting into the air, the scrambling crowd of villagers, and the native’s livestock. The filmmakers desperately want to document a Tree People attack, so they herd the terrified villagers, mainly women and children, into their thatched huts, and set them afire, while keeping the villagers in the huts with their guns just so they can watch them cry out and burn to death, filming the resulting confusion and atrocity so that it can be edited together in the future. After the massacre, Alan and his girlfriend Fay fuck, rutting like animals on the ruins of a native hut, while the remaining villagers cower fearfully in the background; when Alan notices that his friends are filming him, he sheepishly tries to ward them off, but luxuriates in the moment.

The film makes no bones about it, the American filmmakers are truly despicable people, and Monroe, taking a break from watching the footage, has a crisis of conscience, and refuses to participate further in the documentary film project on moral grounds. When the network executives balk at his protests, Monroe challenges them to watch the remainder of the footage with him, and they agree, sequestering themselves off to a private screening room to watch the remaining footage. What follows is perhaps the most disturbing part of the film, as the filmmakers come upon a naked woman, a member of the Tree People tribe, and run her down, tackling her, pinning the struggling woman to the muddy ground, and taking turns raping her while the others capture the moment for posterity on film (only Fay objects, and she is casually pushed away by Alan). During the final screening of the found footage, Deodato repeatedly cuts away from the on-screen violence, to the network executives, who increasingly look ashen and askance at the unfolding carnage, looking increasingly sick at the prospect that this footage could every clearly be seen as “entertainment,” and thus I think they are supposed to act as surrogates for the actual Cannibal Holocaust audience. It’s unfortunate for them that their exploits are seen by Tree People warrior who hides in the overgrowth, but before their eventual comeuppance, they come upon the skewered woman (the wooden poll impales her through the vagina, and exits through her mouth) and Alan has the gall to say: “Oh, good Lord! It's unbelievable. It's horrible. I can't understand the reason for such cruelty. It probably has something to do with some bizarre sexual rage with the almost profound respect these primitives have for virginity.”

The screening ends with the final footage the crew shot, the attack of the Tree People. First one member of the crew is dragged away, castrated, and then torn apart while still alive. Like The Blair Witch Project, you kind of have to wonder why they keep filming instead of running, but given the filmmakers maniacal search for authentic violence, as well as obvious delusion of what constitutes reality through the camera lens, it’s fairly understandable. Fay is the next victim, and she is dragged away by the Tree People screaming for help, repeatedly raped and then beaten to death. All of these scenes of carnage are seen in fragments, though the sound is fairly clear through; actually, you barely ever see a clear picture of the attackers, so I may be wrong, and the attackers may be a rival cannibal tribe, the Swamp People. The final shot from the camera is a close up of a dead Alan lying prone on the ground, the camera clearly lying on the ground next to him, his eyes glazed and vacant, blood streaming down the side of his face. When the final frames flicker through the projector, the lights come up, and horrified executives immediately order all the footage destroyed. A satisfied Monroe exits the network’s lower Manhattan offices, musing to himself who the real savages are in voice-over, as he walks down the street. An end title appears on screen, informing the audience that the projectionist was convicted of stealing and selling the presumably real footage.

Needless to say , my viewing of Cannibal Holocaust was not the Halloween fun and games I had expected, but instead a sobering, intellectual look at the complicity and responsibility of the bloodthirsty, exploitation audience in the filmmed violence they devour (though I hazard to say it, since I haven’t seen the film in question, Cannibal Holocaust seems to me to be in the vein of Haneke’s Funny Games). I think it is clear that Monroe’s final verdict is supposed to apply to the audience, and this was one of the reasons that Deodato and Clerici used the found footage motif, to increasingly blur the line between fiction and reality. One would have to ask: If no one would find this material “entertaining” in real life, why is it so when done via fiction?

Quick Notes on Recently Seen, Half-Remembered Films

Kill Bill, Vol. 1: In which Quentin Tarantino downplays his golden ear for dialogue and concentrates on exhibiting his visual talents. The end product may not be the best film ever made, but it certainly feels like one of the coolest. There's an exhilarating, let's-try- this feel to the movie; in some parts, all you can do is grin as you envision QT knocking another item off his mental list of Cool Things I've Always Wanted to Put in a Film. The acting is stellar as well, though it's hard to pick up on at first glance. In particular, I needed a second viewing to fully appreciate Lucy Liu's damn fine work as O-Ren -- it's the little things, like the way she delivers the line "I take your fuckin' head" or the small, satisfied smirk she sports while strolling down the hall accompanied by her entourage. I'm not really convinced the movie's actually "about" anything beyond its own brand of badassness, but then I'm not sure it needs to be. It's living proof that art need not be meaningful to be poetry.

Wrong Turn: Simply awful amalgam of "The Texas Chainsaw Massacre" and "The Hills Have Eyes". It's severely bland and is hampered by some generic and boring villians, as well as a script that appears to have been made up on the fly. There's one good moment involving a concerned policeman; everything else is child-safe filler.

Monkey Shines: George Romero's films have often been concerned with civilization vs. animal instinct but never quite as boldly as in this film, wherein a trained monkey acts on its quadraplegic owner's violent impulses. It's a measured and thoughtful film from a director usually defined by his acts of excess. Jason Beghe's performance as the wheelchair-confined fellow deserves commendation if only because the script requires him to dance tantalizingly close to losing our sympathy by lashing out and acting like a jerk quite often; to Beghe's credit, he keeps his character's outbursts in the realm of the understandable. Add in a stunner of a finale, and you've got one of the most underrated horror flicks of the '80s.

Skidoo: There's a reason this film never made it to home video, despite having a big-name cast -- it's a misfire so ill-judged that the proper response is to gape, as though one were passing a traffic accident. Among the stars roped into this, only Jackie Gleason and Groucho Marx escape with some dignity, possibly because they have enough professionalism and natural personality to inflate even the weakest of roles. Everyone else looks properly embarrassed, though the biggest raspberry goes to songwriter Harry Nilsson -- he penned three or four original tunes for this, yet the only bearable musical moment comes when he sings the closing credits.

Johnny Firecloud: Leave it to legendary schlock producer David F. Friedman to take a "Death Wish"-style scenario, marry it with minority politics a la African-American cinema and -- voila! -- the world's only example of Injunsploitation! The film has a reputation as one of the most vicious and violent of the "Death Wish" clones, and that may be true, but the film drowns itself in bad dialogue long before the promised retribution. Still, it's the only place you're gonna see a rape scene involving Sacheen Littlefeather, so it may be worth a look for exploitation completists.

Bummer!: Well, the title's not a misnomer, which should tell you everything you need to know. We'll move on.

Viewer Discretion Advised: My love for the scrappy output of Troma Studios has gotten me burned more than once. So it goes with this film, a mostly mirth-free resurrection of a long-dormant genre (the "Kentucky Fried Movie"-style sketch revue). In fact, the film pretty neatly sums up why the genre died in the first place -- too many films with bad improv comics starring in dismal spoofs of things that have pretty much been spoofed to death. I'll admit to heartily laughing through one of the fake commercials, and I chuckled at a couple other occasions (although the faux-tractor commercials, though amusing, aren't nearly as funny as the real thing, and I say that as a guy who grew up on Cal Worthington and his dog Spot). By the time the film wrapped with the worst slasher movie parody in existence (even worse than "Scream 3"!), I was ready to call it a day. Heed the advice of the title.

What Have They Done to Solange?: Quite possibly the most baldy sexual of any giallo, which is both a strength and a failing. It's blessed with some wonderfully overheated imagery and ideas, like a killer who's doing in young girls by stabbing them with a knife in that place you'd probably least want a knife if you were a young Catholic schoolgirl in England (or anywhere)... but it's also indicative of the film's spell-it-out methodology that the killer would do this, because, ya know, they're impure and all. This is taken to its extreme during the denouement, where we find out just what Solange has to do with the narrative -- the solutions to the film's enigmas prove queasily stunning even as the climax proper turns out to be stupid as hell. Not bad, but not the forgotten classic its champions claim it to be; still, it's way better than "The House with Laughing Windows"...

In the Cut

Jane Campion’s In the Cut is a bleak and sorrowful film disguised as an erotic thriller that’s really about an attractive young woman getting older and lonelier. Fanny (Meg Ryan) becomes a primary witness for the police when a woman she voyeuristically spies performing a sexual act in a bar bathroom ends up the victim of a serial murder. Fanny is a solitary New York English teacher, keeping a sole friendship with her half-sister Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh), while somewhat dreamily pursuing a personal passion for poetry and linguistics. Tellingly, the kind of linguistics Fanny is interested in is street slang, which she asserts is entirely derived from either sexually roots or violent ones (“Or both,” comments Pauline). Fanny seems boy shy or at least relationship-phobic (apparently she is divorced in Susanna Moore’s novel, which she adapts with Campion) and her pseudo-incestuous closeness with her half-sister (a common Campion trope) is later replaced by a trio of men who surround her and the murder investigation that drives In the Cut's story. The principal male is Detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), the investigating officer on the case, who Fanny alarming recognizes as the man she saw with the victim in the bar the night of the murder. Nevertheless Fanny allows Mallow’s handsome, charming, coarse, and manipulative cop to seduce her, bringing out fits of sexual passion that makes the rest of her sad, minimal life pale in comparison. Question marks also surround Fanny’s neurotic, obsessed ex-boyfriend (Kevin Bacon) and a black student from her class that she is consulting (courting?) about her interest in slang (Sharrieff Pugh).

Though most of the dialog gives the impression the film is interested in who the real killer is the murder plot line is really an excuse to throw attractive and dangerous men into Fanny’s depressed life. If mournfully trekking into Manhattan to teach her class to bored kids only to return to the Burroughs to see her one and only friend who lives above a strip club seems  pathetic, Campion portrays it as particularly tragic by exploring the unusual intimacy between Fanny and Pauline, who discuss the idyllic romantic courtship of Fanny’s mother by the women’s father, and the sad state of both their romantic lives. Pauline laments her relationship with a married doctor who is putting a restraining order on her and she gives Fanny a birthday present of a charm bracelet promising marriage and children. Despite their best efforts to hide it-Fanny with childlike, dreamily long bangs, Pauline who barely tries to take care of her looks and obviously makes horrendous life decisions-both women are obviously bright and attractive. In their depressing lives they are justly shown as constantly seeming on the brink of distressing, sorrowful tears, and Campion shoots much of the movie in a blur of soft-focus, as if the screen itself was constantly being clouded by a choked-back cry. Ryan especially evokes a confused and resigned sadness that underlines one of her best performances (though her nudity in the film is getting most of the attention), and the film feels even less about her opaque, twisted relationships with the film’s men then being a momentary slice of sadness in one woman’s life. Campion’s photography takes a lot of pleasure in the film’s gritty New York settings (filmed “100% In New York City” the credits exuberantly declare), and the many pillow shots of American flags and other locals hint at In the Cut being as much a post-9/11 statement on the character of the city’s female inhabitants as Spike Lee’s 25th Hour did for its male equivalents. Extending the film’s theme of relationship frailty too far, where elements of the killer give devious implications to long term commitment (he leaves a wedding ring on his victims) and the confusing dichotomy between Fanny’s passion and her non-sexual characteristics, occasionally pushes In the Cut far over its head. But taking its simplest, most emotional and most effective elements together-that is, away from the thriller plot line-the film can be a very rewarding and occasionally moving experience.

Pound

Absolutely nothing that would interest me opened this weekend in Madison, so I spent most of my weekend doing laundry and watching Farscape Season 3 on DVD. I did see one movie, however, at the Thursday night experimental film program, which is called Starlight Cinema. I used to be a regular at those screenings, but I haven’t been able to go in recent years due to my work schedule (screenings don’t start until 9pm), and I have only been able to go once this season, when Starlight screened a collection of films and video work by San Francisco artist Jay Rosenblatt. For anyone who is interested, Rosenblatt, a former therapist, is principally known for using found-footage collage techniques to illustrate his psychological musings (from what I have gathered, Rosenblatt is associated with Craig Baldwin, who creates science-fiction influenced, political documentaries out of found footage, such as Tribulations ‘99 and Spectres of the Spectrum), but he also works in film diaries and more “traditional” experimental modes. They screened five of Rosenblatt’s works, four 16mm films and one video; the most interesting were A Pregnant Moment, a film diary chronicling the before and after of his dog’s pregnancy, Smell of Burning Ants a video collage which explores the male socialization of violence during youth, and Short of Breath, a film collage about post-partum depression and therapy.

But I digress, the film that I saw on Thursday was a rare screening of Robert Downey Sr.’s 1970 film Pound; I’ve never seen any of Downey’s other films from the 60s and 70s, as I missed the only screenings of Putney Swope and Chafed Elbows a couple of years ago. I guess Pound has been out of circulation for many years, and the print was in terrible condition (completely pinked with a fairly fuzzy soundtrack). Pound is apparently based on Downey’s 1961 play, in which humans play the part of dogs (as well as one cat and one penguin) trapped in the pound. It’s an amusing premise, but the film itself is pretty hit or miss; imagine a bunch of late 60s, early 70s New York hipsters being wildly non-conformist, mugging mercilessly, and spouting non sequitur and puns in non-stop monologues. Everyone fears “The Needle,” but reacts differently, some plot to kill the Keeper and escape, some seem resigned to their death, while others have concerns so weird they’ve all but disappeared up their own bunghole. Basically, sex and death are on everyone’s minds, and every once in a while the cacophony of the pound is left behind for various musical interludes and fantasy sequences (escaping to glorious freedom, which includes streaking; riding trains; being guided through some pearly gates by an angel). Weaving through the plot is a sidestory about the “Honkey Killer” a middle-class, white serial killer who goes around town gunning down amorous white couples, while refusing to have sex with his wife; His motive, “it’s too free” out there. He’s being pursued by the heavy drinking, black police chief who is convinced that the Honkey Killer is a “brother.” Pound veers wildly between being very funny (the best joke is when the Keeper is held-up, but since she has no money, the robber takes a puppy instead, but then agrees to pay the Keeper $5 for the adoption fee) to just plain tedious. The most interesting thing about the film was an early glimpse of a four or five year old Robert Downey Jr., who plays a puppy brought to the pound (yeah, that and Huggy Bear from Starsky and Hutch, Antonio Fargas, plays a greyhound).

Next week, in honor of Halloween, there will be a screening of Cannibal Holocaust, which is being advertised as “The Feel Good Film of 1979.” I can’t wait.

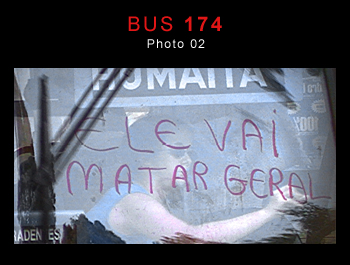

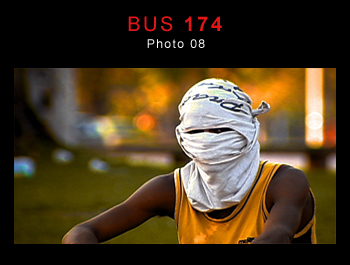

Bus 174

Bus 174  tells the unbelievable story of a crime gone wrong in downtown Rio de Janeiro, where a robbery quickly went to hell and turned into a hijacking of a city bus, and when the police ineffectually responded to the problem the Brazilian media descended on the scene to capture, on super saturated video and in murky TV audio, nearly ever moment of the tragedy from beginning to end. Bus 174 reaches an impossibly gripping level when directors Felipe Lacerda and Jose Padilha simply let the media footage roll accompanied by recollections of the hostages, who both narrate what is happening on the bus as well as their feelings and emotions about the experience. Mike D’Angelo insightfully calls the film a real-life version of Dog Day Afternoon, and at its best Bus 174, for those unfamiliar with the details of the event, invites a level of sweaty-palmed captivation usually reserved for fictional films that are allowed to construct an entire narrative around artificial suspense.

The filmmakers rightfully feel the need to provide a social background to Sandro, the poor robber who got in over his head. Unfortunately the picture Bus 174 creates of the perpetrator is one filled with clichéd generalities, and it seems clear that the political objective of the film is to showcase Sandro as one of a million similar people living in squalid anonymity until their acquire a media spotlight, breaking out of their poverty through violence. Sandro’s mother was killed in front of him when he was a child;

he hit the streets before he was a teen; he bounced into and out of juvenile incarceration as well as jail many times; and he used a variety of drugs. Lacerda and Padilha devote more than half of their film to building a profile on Sandro but always end up with a description that could easily fit the untold thousands of street kids and young delinquents that plague Brazil. More interesting would be to cut out the background of Bus 174 and preface the hostage-narrated raw footage of the hijacking with Katie Lund and Fernadno Meirelle’s fictional crime-epic City of God which similarly devotes most of its narrative to the generic creation of youth crime in the ghettos. The dichotomy and intersection of the fiction and the real would provide an incredibly fascinating look at Brazilian youth, but as it is, Bus 174's sociological investigation is best left to a more broad documentary on the street youth phenomenon of the country, as it does little to deepen or understand the Sandro’s crime.

Dismissing Bus 174's background as purposely too general is a disservice to this often-fascinating section of the film. When the filmmakers explore Brazilian jails for example, ranging from an immense, packed delinquent center, to a jail so dank and dark the jailer himself pities its inhabitants, and a cell block actually filled with criminals who are allowed to speak on camera, Lacerda and Padilha’s sociological tangents are often interesting and insightful despite their generalities. These tangents are usually more interesting than Sandro’s relatives’ comments, or the film’s consulted sociologist who continually insists on the obvious-that Sandro is an example of the invisible, unwanted aspect of society and that the hijacking revealed it before the eyes of Brazil.

The best moments of the film lie in the media’s coverage of the hostage situation, where we can clearly see Sandro stalking back and forth down the length of the bus, hostage in hand, simultaneously yelling to the hostages and to the police, plagued with a confusion of what to do. He does not want to let the hostages go, he doesn’t  have demands, he doesn’t want to die, he doesn’t want to go to jail; the poor man ended up in a situation that started off bad and became worse and is clearly in over his head. (One of the hostages suggests Sandro was high at the time). The hostages who are willing to talk to the filmmakers reveal many unique things that are unseen by the TV camera, for instance that Sandro keeping up a duel dialog with the people outside the bus and the victims inside, trying to get his hostages to act more desperate and upset so he can try to bluff the police. Bus 174 is also a statement at the ineptitude of the Brazilian police and SWAT units, who are so unequipped that their commander is forced to use hand signals (instead of radios) to communicate to the unit on the other side of the bus. One is reminded of the incredibly lack of communication in Bloody Sunday that was a primary cause of the massacre in that film. The fact that Bus 174's most feverish and interesting moments are in the voyeuristic media coverage may be dismaying for those familiar with the hijacking, as presumably a knowledgeable Brazilian would have seen the footage already and thus the interest in Bus 174 would be the filmmakers’ investigation to the background of the crime. This aspect, of course, is the most derivative and unhelpful of the film and raises the question that after initial viewing, and thus familiarity with the event, how much does the construction of the film Bus 174 really tell us about the situation. This is assuming that one simply dismisses the film’s documentary background to Sandro and his street life, which should not happen. But the ineffectualness of the filmmakers to explore the event as unique restrains the potential of the material; the only possible way this structure would work would be to conclude the film’s sociological investigation with a number of similar crimes. Portraying just one gives the hijacking a watershed importance that Bus 174 never really backs up.

|

|