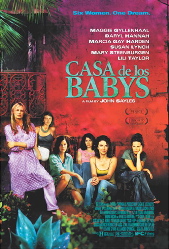

Casa de Los Babys

John Sayles is back with another socially conscious drama, this time about the adoption of Latin American babies by wealthy American women (like his earlier film, Men With Guns, Casa de Los Babys is one of those films set in an unnamed Latin American country, and a considerable amount of the dialogue is in Spanish). It’s not a bad film per se, but it definitely is not among Sayles’s best efforts, it’s another example of one of his sprawling, multi-character dramas that seeks to earnestly dramatize just about every possible viewpoint regarding the issues at hand. The set-up is conducive to his goal, as the film centers on six American women, all of whom are staying at a relatively upscale hotel and are in the process of wading through the red tape necessary to adopt a local child. The women include a thirtyish, New York cynic and prospective single mother (Lili Taylor); a recovering alcoholic who is the most accommodating of the bunch (Mary Steenburgen); a gauche young woman from Virginia who is struggling to keep her marriage together (Maggie Gyllenhaal); an Irishwoman from Boston, whose husband has recently lost his job (Susan Lynch); a New Agey fitness buff who has suffered through three miscarriages (Darryl Hannah; btw, what happened, did Hannah recently get herself a new agent?); and an abrasive, casually racist, possibly crazy, Midwesterner (Marcia Gay Harden).

Swirling around these women are other characters whose stories intersect with there own, even if only tangentally. There is the hotel owner, Senora Munoz, who conspires with her brother, a local lawyer, to bilk the women out of as much money as possible (and she’s bitter towards her exiled, ex-radical husband); Senora Munoz’s son, who works as a handy man at the hotel, but who is a firebrand radical who decries the adoption of the Latino children as another form of “cultural imperialism” (he has been deemed an “enemy of the state” and must keep his job to avoid jail, though he does little but get high and drunk, while articulating some rather banal political sentiments). Then there is Asuncion, a young maid at the hotel from the poor, hillside shanty towns that ring the more prosperous central city; we later learn that she gave up her own child for adoption in the US. From there on out, the ensemble’s relationship to the central storyline is more and more tenuous, there is Celia, a pregnant 15-year old girl, whose rich family is forcing her to give the baby up for adoption (so we have two examples, from two very different socio-economic classes of women forced to give up their children); an out of work construction worker who wants to escape his impoverished country and go to the US, to work in Philadelphia (we meet him several times, at first he attempts to apply at the hotel; then he ends up acting as a tourguide for Gyllenhaal and Hannah; and lastly, we see him desperately try to round up some money for a fake passport by playing the national lottery, and come tantalizingly close to winning, and in case it is not obvious enough, it’s clear that there is a metaphorical link between playing the lottery and getting a baby); and a trio of gas-huffing street kids, who beg in the markets near the hotel.

Say what you will about Sayles, but he’s one of the few high profile writer-directors who can actually write good roles for women and minority characters, and just about every character in the large ensemble is given a moment to shine (there’s also several other minor characters that pop in and out of the story, like Reynaldo, the young student who got Celia pregnant, Celia’s overbearing mother, and a nun and nurse who work at the orphanage), with a monologue or two about this or that subject (or preachy speech in many instances). Oh, and do these women talk. Forced to sit around for days on end, the women have formed a loose coalition (I would hesitate to call it a friendship in many of the instances) where they bitch about each other, about the long wait, about motherhood (and how this or that woman would not make a good mother), while casually displaying a certain level of arrogance that often shades into outright ignorance, condescension, and racism. Harden’s character is the most obvious “ugly American,” but judging by the actions of many of the other characters, you wonder if they notice what is going on around them. For example, Lynch’s character gives a book to one of the illiterate street kids, as if he would have much use for it (he does tote is around for a while, but eventually tries to desperately sell it to any passerby).

The reaction of the Latin characters is mixed, some like Senora Munoz’s son, are very, very angry (his uncle is angry to, but he exploits the Americans for as much money as possible), while Senora Munoz herself sees the Americans as a mealticket. The young construction worker makes an offhanded remark about babies being his countries #1 export, while Asuncion is too busy working to pay much thought to the subject, though at one point she tearfully expresses some mixed emotions to Lynch’s character (though they can not understand each other) when she talks about her own daughter. Celia and her mother inhabit much of the same world as the American women, so they are not shown to give any thought to the subject; in their own instance, the adoption is a necessary thing to maintain propriety. Though some of the characters are obviously mouthpieces, really there only to give voice to some political sentiment (i.e. Munoz’s son), it’s hard to gauge what Sayles really thinks about the situation, since he weaves the homeless street kids in and out of the narrative, as some sort of counterpoint, an example of what happens to the children once they are too old for the orphanage. I mean, it's nice that Sayles has not made either side of the adoption divide just saints or sinners, but it would be nice if he would offer some kind of solid viewpoint on the subject.

No matter what, however, I can always count on Sayles when it comes to narrative experimentation, especially when it comes down to his endings. Since the film begins with the characters in a state of flux, it pretty much ends in a state of flux, with two of the American women being abruptly called to the orphanage to pick up their babies (Marcia Gay Harden’s character has proved to be such a pain, that her lawyer just wants to get rid of her, so he expedites her process, while it appears it was just Lynch’s turn, though Harden’s character in a particular loathsome turn, takes credit for the success of her application, telling her she “put a good word in for her), while the other characters are presumably waiting in limbo. The film actually reminded me of Limbo, since the film even ends before the two of them receive their children, ending on a freeze frame of the babies being carried out of the nursery by some attendants.

Friday Night/Vendredi Soir

Well, I’m trying to dash this off short review off. I actually saw it last Monday, but I haven’t had time to write about it lately, and today I’m been preoccupied with college football (don’t ask), but I’m trying to get this up before I go to a screening of John Sayles’s new film, Casa de los Babys...

Ah, there’s no better way to symbolize modern ennui than a traffic jam, and Claire Denis takes advantage of this somewhat cinematic cliché by having her initially indecisive heroine, stuck in traffic, dig through belongings that were packaged up for charity, and then rescue a few choice items from her past life. In short, this one scene is evocative of the entire whole, as Laure (plainly sexy comedic actress Valerie Lemercier), on the cusp of moving in with an unseen boyfriend, and starting a new, domestic, phase of her relationship, is afforded a new view on her life after a chance meeting with a charming stranger named Jean (Vincent Lindon). It’s a relatively simple story, Laure and Jean meet, they flirt, they get a hotel room, they have sex, they go out to eat, then return to have more sex, and then to sleep, and then she leaves the next morning.

Not that Laure seems all that keen on the idea of domestic “tranquility” in the first place (the best example would be her glum, seriocomic fantasy of herself and Jean visiting her friend Marie’s apartment, crying baby and all, captured by Denis in a curious iris in and out). Denis and her screenwriter, Emmanuele Bernheim (who also wrote the novel the film is based upon), realistically conveys Laure’s mixed emotions that such a a radical life change would elicit, the acquiescence (an elderly neighbor, rummaging through her discarded belongings, is amazed at what Laure is throwing away; later we learn that she is selling her car, though she still thinks it is a “good car”), reluctance (the ominous insert close-up of a new set of apartment keys labeled “Our Place”; or how Laure lolls about on the bare mattress of her twin bed), and resistance (Laure tries on the sexy, red and black skirt, and eventually decides to keep it). One could argue that Laure’s reliance on pay phones instead of investing in a cellphone is another sign of resistance, or an assertion of some level of independence. Because Denis typically eschews a standard narrative in favor of elliptical impressions (at least in the last two films of hers that I have seen, Beau Travail and Trouble Every Day), one has to look at these sorts of minor details and build up the characters from there, otherwise, given the anti-psychological bent of her films (repressed desire being the rule of the day), all her characters would resemble cyphers.

It’s also interesting that Denis’s elliptical narrative style combined with Agnes Godard’s camerawork gives rise to a dreamlike quality which contrasts nicely with Denis’s interest in desire and physicality. We see it again in Friday Night, whose dreamlike-tone is further assisted by Dickon Hinchcliffe’s wonderful ethereal, score; the absurdism of the traffic jam; the deserted back streets, cafes, and hotels of Paris; and the ambiguity of the narrative itself (the majority of the film’s action takes place after Laure has dozed off in her stalled car; and after Jean takes the wheel, roaring through the now empty streets of Paris, it has a certain, nightmarish, yet exciting quality, for Laure). Then there are the sex scenes themselves, which would present themselves as central to a film ostensibly about a one night stand, but here they are as oblique and elliptical as the narrative themselves, more like a sense of impressions emphasizing physical contact over intercourse, giving privilege to a caress or kiss, often shot in underlit rooms, or slightly out of focus, in extreme close-up or from strange angles, atomizing the two bodies, with a measured and controlled soundtrack. There’s actually very, very little nudity in these extended sex scenes (when they first have sex, they are almost fully clothed). Even with a female director, screenwriter, and cinematographer (as well as wedding the narrative almost completely to Lemercier character’s subjective POV), I would hesitate to the sex scenes “feminine,” though I doubt any male director would have shot them in a similar way. Though, I don’t actually think the sex is the end all be all of the film (Denis spends just as much time filming out in the traffic jam, or the bonhomie and warmth of an Italian restaurant that fills slowly with weary refugees from the traffic jam, though this sequence kind of confused me, since I’m not sure if Jean actually had sex in the bathroom with the older customer’s young, angry wife, or if it was another fantasy on the part of Laure), but of the sensations and feelings of a woman on the verge of something....

Bits and Bites: The Dark Lover Returns

Note: In conjunction with the publication of Dark Lover: The Life and Death of Rudolph Valentino, the Museum of Modern Art in New York recently screened several of Valentino's films. Below are quick reviews of two of them.

(image from posteritati.com.) (image from posteritati.com.)

Monsieur Beaucaire: There's a really funny, very charming Ernst Lubitsch movie named Monte Carlo. Its climax revolves around an opera named Monsieur Beaucaire, about a prince masquerading as a barber. When I found out that a movie named Monsieur Beaucaire, starring Rudolph Valentino, was showing, I dropped everything and went.

Valentino plays the Duke de Chartres, a prince of France. He is quite the ladies man, so much so that the convent-raised Princess Henriette refuses the king's command to marry him. They, of course, start to fall for each other. His growing admiration for her leads him to insult the king's mistress, and he is forced to flee to England and "become" a barber.

The movie has serious flaws. It's theoretically a comedy, but it's too long and moves too slowly - nowhere near as light-hearted and funny as the Lubitsch version. There were technical bloopers as well: in one scene of Valentino in a medium shot, wearing a light-colored coat, the studio lighting throws the camera's shadow on Valentino's torso. For 1926 and the kind of star Valentino was at that point (post-Sheik / Blood and Sand / Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse), that's pretty inexcusable.

One interesting sidebar to the movie: this film fed into the press controversy over Valentino's sexual orientation (AKA the "pink powder puff" scandal). While women swooned, some men were jealous and the press questioned Valentino's manliness. With respect to the movie, what they may have clued into is not Valentino's personal life, but his inconsistent depiction of a prince. Valentino just doesn't look up to snuff. There are movies where he is quite the eye candy, but this isn't one of them. The man bounces on the balls of his feet when he crosses the set! In one scene he stands shirtless - but he's too skinny to be a reckless sword-dueling prince. (Buster Keaton, very physically fit despite usually playing a weakling, was much more bulked up than Valentino.) All in all, a disappointment - although it does point out the genius of the later Lubitsch work.

Cobra: A much better outing. Valentino plays Rodrigo Torriani, an Italian count / ladies' man persuaded to move to New York and work for Jack Dorning, an American antiques dealer. Because of his friendship for Jack, Rodrigo passes on two women who could have potentially turned him around. The first woman ends up marrying Jack; Rodrigo, in a momentary lapse which he rights, ends up involved in her death. Rodrigo has to deal with feelings of lust and guilt mixed in with his friendship for Jack. Because of these feelings, he ends up passing on the second woman, Mary, the only "pure" woman that he ever loved. Cobra: A much better outing. Valentino plays Rodrigo Torriani, an Italian count / ladies' man persuaded to move to New York and work for Jack Dorning, an American antiques dealer. Because of his friendship for Jack, Rodrigo passes on two women who could have potentially turned him around. The first woman ends up marrying Jack; Rodrigo, in a momentary lapse which he rights, ends up involved in her death. Rodrigo has to deal with feelings of lust and guilt mixed in with his friendship for Jack. Because of these feelings, he ends up passing on the second woman, Mary, the only "pure" woman that he ever loved.

Valentino is closer to form in this movie. His portrayal of a well-meaning philanderer is much more convincing, and the movie's backstory (Italian migrating to the US) reflects Valentino's own history. The technical issues are now virtues; in fact, there is one shot, after he decides to give up on Mary for Jack's sake, of Rodrigo leaving a room by pulling the door shut. As his head turns, you see the gleam of a tear in his eye. Without crying, without wiping his eyes, without much more than a hung head, Valentino's whole gesture belies the bluster he has just put up. Poetry, people, poetry. And the amazing thing is: this is Valentino at the height of his popularity, and he doesn't get the girl. He makes his sacrifice; the next shot, he's on the deck of a ship headed back to Italy, and then "The End" appears on the sceen. Wow.

NYFF: Elephant

Of the many ways one could make a film about school shootings the way Gus Van Sant approaches the subject in Elephant is certainly the most unexpected, and without a doubt the most unsettling. Loosely based on the Columbine massacre, Van Sant has created a fictional account of a similar shooting in a Portland high school. Elephant’s brief running time concerns itself mainly with following around various students, introduced through title cards and characterized almost entirely through banal conversations and the camera’s gaze, as they walk around their school fifteen minutes before the shooting erupts. With two exceptions Van Sant eschews looking at classroom life, or even the complicated social life in high school in general, and is content to track a handful of non-exemplary students through hallways, across green fields, and in and out of their library and cafeteria until all hell breaks loose.

The mood provoked is dreamy and could almost be described as romantic. Cinematographer Harris Savides glides his steadicam behind and around the students in immensely long, uninterrupted shots of traveling time between class, and the beautiful Portland area soaks Elephant in warm light and gorgeous green surroundings. As Van Sant’s camera follows one student while he or she walks, various students are glanced in the background, and the camera later to them, and follow their limited path for an equal period of time; the result is a poetic and oblique picture of the connections and disconnections between students, other students, and their school. If anything, the style intensely emulates the rhythm of a school day, where the periods between classes, no matter how mundane, are usually the highlight and where it seems like everyone is on their own path, doing their own thing. When students meet or run into each other, as occasionally happens between a boyfriend and his girlfriend, or two acquaintances, the conversations are improvised and banal, mere greetings and offhand teenager chitchat. Though all the teens in the film are actors, their dialog is improvised and their characters are loosely based off their own persons and their character names are taken from their own. The general non-specifics of the entire film immerse the viewer in a languid, abstract world where there are no events and no consequential dialog; Elephant is more an experience than an explanation.

Probably the most incentive element of Elephant, at least for a bred-and-raised on mainstream film person as myself, was the way convention is used in the film’s aesthetic. Knowledge that the film’s subject is school shootings coupled with the wistful, eventless photography builds an unusually wicked tension as one waits and waits and eventually longs for the “climax” to come, the dream interrupted. For me, it was one of the most disturbing emotional provocations felt in cinema, all the waiting for the car chase of The Matrix: Reloaded or the House of Blue Leaves in Kill Bill Volume 1 transferred to the most wrong of places.

Luckily, in a film with this dreamy and intangible of an atmosphere, a number of very overt narrative decisions stand out like slaps to the face and momentarily distract one from the carnage to come. These include a scene of the two killers waiting for their guns to come in the mail and watching a documentary on Nazis in the background, a similar shot of one of the boys playing a violent videogame, a scene where three beautiful girls simultaneously force themselves to vomit their lunch, a rare classroom scene where one of the killers is pelted with spitballs, and a kiss between the two male killers before they go to their last day of school. But before one can accuse Van Sant of pandering to the direct-though much criticized-inspirations for such a shooting one must look at another strange aesthetic decision of Elephant. With only one exception in the cast of about a dozen every teenager in the film is attractive, having an almost model-quality beauty. Yet there is one girl who is clearly visually labeled as a “nerd.” One would expect this to make some sort of point, but Van Sant negates it by having her be the first one shot. Similarly, several teens setup as “jocks” or “beautiful girls” are nearly introduced as such but not shot. While watching the Nazi film, one of the killers asks with complete naivety “Wait, is that Hitler?” and “Wow look at all those flags,”-not exactly the kind of utterances people assume the Nazism is inspiring in these future killers. Their motives are just as oblique as the film as a whole, or teenagers in general; Van Sant inserts the easy answers but makes sure that their interpretive powers are practically nil. Left without answers one is drawn into the evocative atmosphere of Elephant, a film named after the idea that what no one wants to talk about what is clearly obvious and tangible, but an uncomfortable subject. Ironically, Van Sant has crafted an experience that defies this idea, making the dangers within schools and amongst teenagers as oblique and mysterious as they truly are. That the danger exists there is no doubt, but after drifting around the halls of the school one will be hard pressed to find an elephant; if anything, there are creepy, shadowy glimmers of inherent tension, but searching for pure inspiration is a fool’s journey. A smart conclusion for a particularly smart film.

Question of the Week

The Unofficial Milk Plus Canon, Part II: 1995-1999

Given the monumental success of the Unofficial Milk Plus Canon 2000-2003, you knew that a sequel was inevitable. So here goes, but this time it's bigger (a whole five year period this time) and badder then ever. Remember, this question is open to all blog members and readers, so get your list in, so your vote wil count:

Create a list of the Top 10 films released between 1995 and 1999, providing rationale for each choice.

Usually, these types of lists are done by decade, but I've decided to use a five year format which should add a bit more variety to the mix, as well as make our choices easier (in theory). Because of the variability of release dates, I've decided to institute the following ground rule so we can get some standardization: Please use release dates (by year) as they appear at IMDB.com. I will use the same point system as before, with your #1 movie being worth 10 points, your #2 movie being worth 9 points, and so.

Polling ends at 9pm CST on 10-23. Please have your lists submitted by then.

Update: Please remember, polling ends tonight (10-23) at 9pm CST, so get your vote in before then.

|