Winged Migration. ( Le peuple migrateur, Travelling Birds). Dir. Jacques Perrin, et al.

Not all birds travel as far as the Arctic Tern, winging from Pole to Pole; or stay at sea as long as the albatross; but even flightless species such as the Rockhopper Penguin (travelling 600 miles on South Atlantic currents), or solitary birds such as the Bald Eagle, migrate.

But - even if you've never had any interest whatsoever in ornithology - see this film, and see it on the big screen. It's visual poetry. The work of fourteen cinematographers and seventeen pilots, spanning every continent, and taking over three years to make (not to mention the "cast of thousands!"), this film is well worth watching (and re-watching) for the aerial and landscape cinematography alone.

Some favourite scenes and images:

* The opening shot. A winter scene, along the Eure(?): falling snow dusts the river, an old shelter in the foreground, church steeple and village in the background. The scene fades into spring. Simple and quiet beauty.

* A brief glimpse of the Great Wall of China from the air: sinuous, ancient and impressive, rising out of a misty landscape. One glimpse also of Mont St. Michel, a quiet island standing in blue-grey waters.

* Sandhill Cranes in an African oasis. Wave upon wave of dunes gives way to the calm of a river; rushes and palm trees golden on its shores. In the evening, open fires flicker in the distance.

* In the Arctic, glaciers calve and crash. High in the Himalayas, a warning rumble precedes the tumble of a avalanche.

* Somewhere in the American Southwest, birds exuberantly swoop into a river canyon, followed by the equally joyful camera. Elsewhere, the camera looks down on a flock as it glides above a still lake, the textures of its banks perfectly reflected and detailed in the water.

* Contrasts in colours: a flock of geese, in V-formation, above intensely yellow and green fields in France. Later, an echoing shot of a another flock, this time in W-formation, stark white against the rusts, russets, and brilliant reds of autumn in the northeastern U.S. Flying to the Arctic, we pass a white landscape streaked with browns, blues and greys - a shading of crevasses and subtle colours. In the Amazon, the vibrant reds, yellows, and blues of tropical parrots seem supremely fitted to its lush domain. A flock of cranes in Africa, silhouetted against a blood-red sunset. Storks, formal in black-and-white, dance on a snowy plain.

* Whooper Swans, migrating from the Far East to the Siberian Tundra, traverse a timeless landscape of verdant rice-paddies and bullock-driven carts. Across the globe, in an equally timeless image, a babushka, scarf over her head and bucket in hand, comes out from her stone farmhouse to hand-feed storks who make a brief annual stop on her property.

* The camera swoops with a flock of geese along the Seine, under bridges, past the replica of the Statue of Liberty at Pont de Grenelle, the Eiffel Tower in the background. Later in the film, another flock silently passes the towers of the World Trade Center and the original Statue of Liberty on Staten Island, donated to the U.S. by the people of France.

And there are moments of high comedy too. Even resisting the temptation to anthropomorphize, you'll have to laugh at some of the birds' antics: the seabird trying to swallow a fish patently (almost) too large for its gullet; the Amazonian parrot that must have seen too many screenings of Chicken Run (delightful, even if obviously rehearsed).

As for the "aaaww" factor? Springtime, and new life: Cygnets, goslings, owlets, and ducklings - as well as baby storks, penguins, and numerous other species. All disarmingly cute. As my friend Tom said, it gives a new meaning to the term "chick flick".

Two minor caveats: The music, by Bruno Coulais, may be a tad intrusive for some. I loved it - loved the range in styles and mood. But some viewers may occasionally find it too much of a good thing.

Also: although no special effects were used in filming the birds' flight, there was some staging of scenes, either through use of editorial licence to create a dramatic "narrative", or through the filmmakers' intervention. Some flocks were imprinted on the filmmaker/ornithologists, thereby enabling the latter to fly ultralight planes alongside the birds. Given the results, I'll happily accept this minor tweaking of documentary parameters. Even if one knows, that - for example - the film-makers and flocks didn't just happen upon an aircraft carrier in the middle of the ocean; or that both birds and camera were safely out of avalanche-range in the Himalayan scene, it doesn't (for me) detract from the incredible quality of the film, and the extent of the filmmakers' dedication and skill.

Thankfully, there is almost no narration. Very brief (and in my opinion entirely adequate) captions name the species and their migratory paths. This is not an "educational documentary" in the style of National Geographic (worthy as those may be).

It's a celebration of film, flight, and our natural world. Its prosaic title, lacklustre publicity posters, and unprepossessing subject ("A documentary? All about migrating birds?") don't give any hint of just how magnificent this film is. Anyone interested in film or photography - or, of course, birds - will find it an intoxicating and joyful experience, seeing Earth's beauty through the soaring, exultant lens of Winged Migration's camera.

-copywright.

Battle Royale

Let me begin by first saying that this review is based upon my viewing of the two-disc, Regionless “Special Edition Director’s Cut” DVD (which runs approximately 122 minutes, it’s actually a Korean import); I guess there are several versions floating around, and phyrephox and I had some AIM discussions over which version I was actually watching. Basically, the movie was released in Japan rated R-15, which is the Japanese version of an R-rated movie; it was a big hit, so to make some more money, they reedited the film so they could release it with a lower rating; then I guess some member of the Japanese Diet denounced the film as an example of Japanese popular culture run amok; later, the director Kinji Fukasaku created another director’s cut version, with footage that expanded the relationships between some the of the characters, I think this is the version, or closest to that particular version, that I watched last night (the version I watched had a R-15 rating preceding the movie).

Battle Royale is a film whose reputation for being ultra-violent has definitely preceded it, though, truth be told, it’s really not much more violent than a Verhoeven film, it’s just that in a Verhoeven film, a bunch of 14 and 15 year olds aren’t the ones killing each other. Kinji Fukasaku took a novel by Koshun Takami, and fashioned an artful movie in the guise of an exploitation thriller (my favorite). The admittedly absurd premise takes the form of a classic exploitation thriller: a class of 42 Japanese students are taken to an isolated, uninhabited island by the fascist government, where they are armed (with an assortment of weapons, from a pot lid to a MP5 submachine gun) and set loose, with only one purpose, to kill each other. After three days, there can only be one survivor of the Battle Royale; if there is more than one survivor at the end of the game, everyone dies, courtesy of the explosive, tamperproof necklaces that each player wears around their neck. And to make matters more interesting, certain zones of the island are deemed “danger zones;” anyone in the them, will suffer detonation, so the players are constantly on the move. While I’m not exactly sure what the Battle Royale is supposed to accomplish in the eyes of the government (other than scapegoating; the high school class is selected by random lottery, and the class doesn’t seem to be full of juvenile delinquents; it’s pretty much an adults vs. youth story), the premise is a launching pad for a film that is thrilling, horrifying, tragic, and ultimately hopeful.

The film has a rather large cast. Though the filmmakers focus only on a handful of the 42 students, all are given equal opportunity to shine in the various death scenes, which are mostly featured in vignettes of various length, many of which feature flashbacks, voice-over narration, and intertitles which elucidate the relationships between the various students (the image of Japanese teenagers in school uniforms, especially the girls in their skirts, is both striking, funny, and horrifying). After each vignette, a title appears on-screen telling the audience the names and student ID numbers of each person killed (and the adults on the island give periodic updates over an island-wide PA, a ghoulish roll-call of the deceased). As I said before, the film focuses on several of the students, in particular, Shuya Nanahara, an orphan (his mother died of an illness, and his jobless father hung himself; Shuya found his father’s body after his first day of 7th grade, and his suicide note, written over and over again on long lengths of toilet paper, “Go Shuya, You Can Make It, Shuya) who promised his friend Nobu (he dies rather early in a demonstration of the explosive collars, though he reappears in flashbacks and fever dreams) to take care of the girl that he has a crush upon, Noriko. Other important students include the two Battle Royale participants who were not part of Nanahara’s class, the enigmatic, experienced Kawada (who has his own dual reasons for participating in the Battle Royale), and the psychopathic Kiriyama, a true badass who joined the Battle Royale for fun (and manages to gleefully dispatch the majority of the students, with his only expression, if you can call it that, being a contemptuous sneer and wry smile). While Kawada ultimately comes to the aid of Shuya and Noriko, Kiriyama mercilessly hunts down the other students. Rounding out the featured students are Sugimura, a genial boy who continually is searching the island for someone; Mimura, a computer hacker who organizes some of the other boys into plotting against the adults on the island (his uncle was a leftist guerilla and taught him how to make bombs); and, finally, Mitsuko, who I’m pretty sure was the class slut. She transforms into a particularly heartless killer, but of all the students, her backstory is particularly revelatory, especially during the first Requiem sequence (the version of the film has three Requiem sequences, a basketball match between Class A and B, a happier event which repeatedly punctuates the film in flashback; there is also two extended dream sequences, which partially appear earlier in the film, one of which expands on the relationship between Noriko and Teacher Kitano), where you see how lonely, friendless, and ostracized Mitsuko really is (her class wins the basketball game, and their lots of hugging and cheering, and though Mitsuko is clearly happy, she’s alone in the back, friendless).

Of the adults, the only one of real consequence is the stoic and sadistic “teacher” Kitano, played by Japanese renaissance man Takeshi Kitano. Ironically, Kitano was once the student’s actual teacher, until he got sick of being mocked by his students (and after having his leg slashed by Nobu after class); now he orchestrates the Battle Royale carnage, personally dispatching two students during the Battle Royale introduction (he throws a knife into the forehead of a girl who was whispering, and detonates Nobu’s collar as demonstration for the others, it’s pretty gruesome with the hissing spray of the ruptured jugular), a deliciously wicked sequence of horror and black comedy.  The students, completely terrified, huddle in a decrepit class room, surrounded by soldiers armed with assault rifles, and are forced to watch an official tape which explains the rules of the Battle Royale. What’s funny about this sequence is the tape, which seems modeled after a Japanese commercial, with a punkisly attired young woman exclaiming the rules of the Battle Royale in a characteristically high-pitched, easily excitable voice. Battle Royale is filled with such moments of black humor, many of which are provided by the impassive face of Kitano himself (I’m thinking of the ending, in particular, after being shot repeatedly, his cellphone rings, and he gets off the floor, answers the phone, shouts at his estranged daughter, eats a cookie that Noriko baked, and then dies). Kitano, the character, is revealed to be much more than a mere sadist, or vengeful adult. He has a genuine affection for Noriko (yes, kind of off-kilter and weird, but still tender and sympathetic), and from the few snippets of phone calls he receives from home, you can tell that Kitano is a desperately unhappy person, taking out his misery and frustration on others (you get the impression that the government, is taking out it’s own misery and frustration via the Battle Royale; and in many ways, is acting like a petulant child).

For a film that is very heavy on action (which varies in intensity from black comedy, to brutal realism, to extended, operatic action sequences), it’s strength relies on the relationships, both negative and positive, between the young cast members. Just imagine the lengths that hormones, petty jealousies (“you stole my boyfriend”), cliquish mistrust, fear, stupidity, and adolescent slights, whether real or imagined, could drive a young teenager to, and then magnify that by a factor of ten, hell a hundred. Several of the young couples pull a Romeo and Juliet, committing suicide together rather than being forced to kill, while friendships are torn asunder (for example, as Kitano reads out the litany of the recently deceased, the camera pans across a scene of the bodies of two schoolgirls, who clearly killed each other; there is a quick flashback to the Battle Royale introduction, as the same girls pledge their continued friendship). Many of the students attempt to band together, but even under the best of circumstances, the alliances are fragile (the scene in the lighthouse where a seemingly amiable group of girls degenerates into a hail of gunfire and blood after an accidental poisoning). Young love runs rampant through the group, often with tragic results (I’m thinking of Sugimura’s fate, as he is killed by the panicky girl he’s been searching the island for; with his last few breaths, he tells her he loves her, and she falls to her knees crying, saying how he never even talked to her).

Despite a set-up that seems primed for an embrace of a winner take all, dog eat dog, nihilism, Battle Royale is ultimately a hopeful film, because, many of the characters directly repudiate that kind of ethos (many do so throughout the film, albeit temporarily, as they are either killed or forced to kill), banding together for a common good. Mimura is a representative of a political style of resistance; he wants to fight the adults and their fascist regime, even if he’s to die in the process. He won’t give up, and though he personally fails, his sacrifice lays the groundwork for the others to escape. On the other hand, there is the trio of Nanahara, Noriko, and Kawada, who band together out of personal and emotional reasons. It’s the lone wolves, like Kiriyama, Mitsuko, and Kitano who die alone (though you kind of feel sorry for Mitsuko and Kitano as more of their personalities, and what drives them is revealed; Kiriyama is just a bad-ass sociopath, a tough evil motherfucker who goes against the other tough motherfucker, Kawada, though he has a heart of gold, in a vicious gun battle set in a hellish inferno). These bonds extend beyond the Battle Royale, as Nanahara continues to live up to his promise to protect Noriko, but now, instead of having to protect her from the other students, he has to protect her from the government, who hypocritically, have deemed the two of them murderers.

The Wicker Man

The Wicker Man The Wicker Man, 1973 (starring Edward Woodward, Christopher Lee and Britt Ekland, directed by Robin Hardy).

Cinefantastique called The Wicker Man "the Citizen Kane of horror films." I'm not sure The Wicker Man can really be said to be a true horror film, although if you had to put it on the shelf at your video store, and your video store didn't have a "cult" section, I guess horror would be the most logical place. Some horrific things happen in it, to be sure, but until the end it's not a particularly scary movie. Chilling, creepy and thrilling, but not "sleep with the lights on in the bathroom" scary.

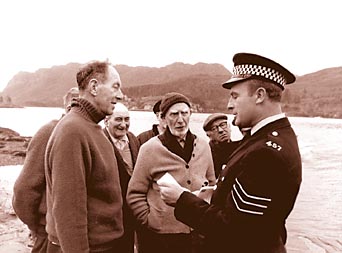

Edward Woodward (later known to American audiences as "The Equalizer") plays Sgt. Howie, a pious, strait-laced policeman investigating the disappearance of a young girl on an anonymous tip. His search brings him to the remote Scottish island village of Summerisle. He's not very successful in finding the girl (not at first, anyway). What he does find is hedonism, pagan rituals, a dead rabbit, and public displays of affection that would make Hugh Hefner blush.

Summerisle is a harvest village. Its livelihood comes from the exportation of fresh fruits and vegetables, so the inhabitants' lives revolve around a successful harvest. They are almost entirely cut off from civilization, and most of the families living there have been there for generations. So it's not really surprising that they practice a pagan religion revolving around fertility and reproduction.

Sgt. Howie happens to come to town just in time for the May Day celebration. Fertility rites are in full swing. Everywhere he looks, Howie encounters perversion and nudity: bawdy songs about Willow the landlord's daughter (Britt Ekland), couples having sex in the yard, young girls dancing naked around a fire pit, not to mention Willow's erotic dance of the temptress in the room next to Howie's, while he's trying to say his prayers.

Howie is shocked, offended, and – let's face it – horny as all get-out. Of course, he doesn't act on his impulses, tempted though he may be. "No offense meant," he mutters to Willow the next morning. "I just don't believe in it... before marriage." Instead he channels his moral outrage and his bottled up sexual frustration into the hunt for the missing girl, Rowan Morrison.

His search eventually leads him to the manor of Lord Summerisle (Christopher Lee), the owner of the Summerisle farming community, and also their civic and spiritual leader. Christopher Lee brings wit and a cool sophistication to his portrayal of Lord Summerisle, and he's the perfect counterpart to Woodward's apoplectic Bible thumper. Their first scene together is one of the highlights of the film.

Sgt. Howie slowly begins uncovering some leads in his search for Rowan Morrison. He first believes her to be murdered and buried in an unmarked grave, until he exhumes the "body" and it turns out to be a dead rabbit (March hare, to be more accurate). But when he discovers that young Rowan was the queen of last year's unsuccessful harvest, it gradually dawns on him that the inhabitants of Summerisle are planning a sacrifice for this year's Rites of Spring – a human sacrifice.

Edward Woodward as Sgt. Howie manages to pull of a tricky acting feat – he's at once judgmental, blustering, self-righteous, and yet somehow pitiable. At the same time, you root for him, you want him to find Rowan Morrison, and you're as curious as he is to figure out what's happened to her. And always just below the surface is this rage of pent-up sexual energy trying to get out, which he struggles to keep under control.

Christopher Lee's portrayal of Lord Summerisle is the polar opposite: he's charming, cool, unflappable, and smiles easily and often. But under the smile there's still something innately creepy and a little frightening about him.

The difference in their characters reflects a difference in their religious upbringings, as well. Howie was raised as a pious Christian, always taught to deny his baser instincts and the temptations of sin; where Summerisle and his fellow pagans were taught to embrace sexuality. The portrayals of different spiritual beliefs here are even-handed, even if Howie is a little on the zealous side.

Anthony Shaffer's well-researched script is filled with rich dialogue and wit (not unlike another favorite Shaffer script of mine, Sleuth), and Robin Hardy's direction is well paced. The score and songs are haunting, and one song in particular stayed with me for days after I saw it. The music is like an additional character in this film, from Britt Ekland's tempting "Willow's Song" (dubbed, as I understand it, but not sure by whom), to "The Tree Song" as sung around the Maypole, to Howie's plaintive version of "The Lord's Prayer."

There are evidently several versions of The Wicker Man floating around – I received the DVD as a gift from a friend who is a huge fan, and he tells me that there is a 79-minute version, an 84-minute version, and a 99-minute version out there. The DVD that I saw is 89 minutes.

Question of the Week

July 4th is fast approaching, so this week's "Question of the Week," is inspired by that holiday. It's actually a two-part question, since our nation ain't perfect or anything:

What film best represents the positive aspects of American politics, culture, history, and/or society? Why? What film best represents the worst aspects of American politics, culture, history, and/or society? Why?.

This question is open to any blogmember and reader, so while disagreement is encouraged, please remember to be respectful of others opinions, especially with the last part of the question.

Unknown Pleasures & Ringu

With the exception of the Cinematheque, the WUD Screenings, and the Wisconsin Film Festival, Madison is not exactly a place where obscure art films are commercially screened (we get all the high profile ones, eventually), so I was excited to learn yesterday that one of the local art-houses had put together a very exciting program of independent and retrospective films which otherwise would never have screened here in Madison (next week, they begin a screening of Guy Maddin’s Dracula: Pages From a Virgin’s Diary; I know what I’ll be doing on July 4th). This weekend, they brought in the documentary Lost in La Mancha (which I commented upon under Rodney’s more comprehensive review, and which, I later learned, is going to be released on DVD on Tuesday), and the latest film by the Sixth Generation director Jia Zhangke, Unknown Pleasures. Thanks to J. Hoberman’s review in The Village Voice, the meaning of the title, which was actually discussed by two of the central characters in the film, was clarified for me:

”Unknown Pleasures takes its Chinese title [Ren xiao yao] (which translates as "Free of All Constraints") from a poem by the fourth century B.C. Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi that became a pop hit in 2001. It's sung twice in the film...”

China, 2001 (actually the provincial city of Datong, in Shanxi Province, which is where Jia Zhangke is from). One of the film’s greatest strengths is how historically specific is truly is; it’s steeped in the locality of the historical moment, much like the films of Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsaio-hsien, and makes little or no allowances for the Western viewer. The references to the poem/pop hit “Ren xiao yao,” is but one instance of this phenomenon, and luckily, I was able to pick up on some of the more obvious historical and cultural references (though I’m sure I missed plenty): the government crackdown on the Falun Gong sect, the spy plane debacle between the US and China (at one point, when an explosion rocks the neighborhood, one of the characters says “Shit, are the American’s bombing?”), the negotiations for the entry of China into the WTO, and the awarding of the 2008 Summer Olympics to Beijing. Actually, one of the funniest references, is when a local thug chastises one of the main characters, Bin Bin, who is selling DVDs to generate some quick cash, for not being able to move art house films like Xiao Wu, Platform, and Love Will Tear Us Apart. The knowing joke is that the first two films were also directed by Jia Zhangke, while the last one was directed by the film’s DP, Lu Lik-wai. Whoo-hoo, reading film magazines finally pays off.

Not only does Jia Zhangke plunge into the historical moment, but also the local environment. Datong seems to be a city in the state of perpetual decay, a postindustrial wasteland, dominated by both the cooling towers of the local power plant and the oppressively rectangular, concrete blockhouses which house the workers, though no one seems to actually have a job in Datong, except for the police, the hustlers, and the mostly unseen construction crews who are building the Datong-Beijing Highway (everyone being out of work doesn’t stop Bin Bin from saying he lives at the “Textile Mill”). Cramped, crumbling homes; muddy, dirty streets; and the dark, dank youth centers, video parlors, restaurants, and discos (all centers of youthful “escape” and “enjoyment”) are all captured by Lu Lik-wai’s DV camera, adding another, muddier, sheen to the proceedings. And despite the sun-bleached landscape that surrounds Datong, the sky is blotted out by a sheet of low-hanging, gray clouds throughout the film (though it rarely rains, Datong seems to suffer under constant humidity).

The film is ostensibly about two slacker-types, a pair of profoundly alienated, unemployed teenagers, named Bin Bin and Xiao Ji, who, despite there shared vacant stares and seeming inability to do anything else but sit around and smoke, are easy to tell apart from their hair and clothing styles: the more “realistic” Bin Bin has relatively short hair and always wears a white, button-up shirt, while the more “romantic” Xiao Ji sports long hair, which often obscures his face (actually, the only time you see his face is when he is riding his motorbike; the wind pushes his hair back), and a more flashier wardrobe. The film concentrates on the laconic pair, and their relationship with their parents and their girlfriends. Both Bin Bin and Xiao Ji are only children raised by single parents; Bin Bin by a recently laid-off single mother, a practitioner of Falun Gong, and Xiao Ji by a jobless single father (who accidentally happens upon an American one dollar bill, which causes everyone around him to exclaim that he is rich). Bin Bin is dating a high school student, while Xiao Ji pursues a local performer/prostitute named Qiao Qiao (which creates a “love triangle” of sorts between Xiao Ji, Qiao Qiao, and her agent/pimp, who is also her former Gym Teacher). Western-style capitalism may have come to Datong, but it has largely passed by this pair; there is one scene that encapsulates this sentiment, when Xiao Ji escapes his customary poverty, and takes Qiao Qiao to a modern, Western-style hotel, and is unable to work the bathtub faucets (another scene is when a temporarily grateful Qiao Qiao takes Xiao Ji out for noodles, and he begins to describe the opening scene in Pulp Fiction, which leads to a bravura cut to a disco, where Qiao Qiao and Xiao Ji dance, in the style aping Uma Thurman and John Travolta, in that same film, to some rather boring techno music).

Both Bin Bin and Xiao Ji are essentially trapped in Datong, disaffected, wandering aimlessly through the streets, looking for something, anything to do; when they actually do attempt to look for jobs, they are turned away (Bin Bin even attempts to enlist in the army, but is rebuffed after being diagnosed with hepatitis). The film reminded me of the work of Antonioni (ennui and spiritual malaise travels well), minus the bourgeois element; shots are held for such a long duration that they approach boredom inducing lengths (there are also very few close-ups in the film, they generally only occur when the characters are in very cramped spaces, otherwise it’s a series of long and medium shots). The defining formal, and narrative element, of Unknown Pleasures is repetition. The characters constantly find themselves in situations where they act like mindless automatons colliding with a wall; with a little effort, they could escape the repetition, but they decline to do so. I’m thinking of the scenes where Bin Bin and his girlfriend Yuan Yuan repeatedly watch an animated version of the Monkey King story in a decrepit video parlor (the rigid, chaste way they sit next to each other shows little evidence of affection; when his girlfriend breaks it off during exams, Bin Bin barely blinks an eye, though, comically, she thinks he’s hurt and angry); when Qiao Qiao’s pimp has Xiao Ji roughed up (also kind of ironic, as earlier, the pimp told the boisterous, drunken Xiao Ji that he doesn’t fight over women), with his thugs repeatedly slapping him in the darkened hallway of the disco, asking “are we having fun yet?” like some sort of sadistic mantra; when Qiao Qiao tries to escape from her pimp, and he throws her back down onto the bus seat every time she tries to get to the door; or, for a final example, when Xiao Ji’s motorbike gets stuck in a small, muddy embankment, instead of pushing it up the two foot incline, Xiao Ji repeatedly attempts to drive it over the lip of the ditch. In each of these cases, and in other instances, a little effort on the part of the characters would have liberated them, but they do nothing. That is, until the ending, where Xiao Ji proposes robbing a bank with a fake bomb; this criminal fantasy goes predictably awry, with Bin Bin being arrested by some nonplussed policeman, and Xiao Ji fleeing down the newly opened Datong-Beijing Highway. The film ends with Xiao Ji’s motorbike sputtering to a halt, in another scene of repetition, Xiao Ji repeatedly tries to kick start his bike in the pouring rain, before giving up, and hitching a ride from a passing motorist. Bin Bin finds himself in a police station, where he is informed that bank robbery is punishable by death (and where he meekly argues that it was only “attempted bank robbery”). In the closing shot of the film, a Kafkaesque policeman demands that Bin Bin sing for him; he complies, haltingly singing a song that he saw on a karaoke video he watched with his girlfriend, “happier” times indeed.

Yesterday, I also made a resolution to catch up on some films that I have missed, but which have been released on DVD. So, in between Lost in La Mancha and Unknown Pleasures, I went to the video store and rented a pair of higher profile Japanese films, Kinji Fukasaku’s Battle Royale (the director’s cut, no less), and Hideo Nakata’s 1998 international horror hit, Ringu (I was also going to rent Ichi the Killer, but that will have to wait, maybe I’ll pair it up with another Miike film, Audition). I decided to watch Ringu last night, since it was the shorter of the two films, and I thought it would make a nice compliment to the other horror film I planned on seeing this weekend, Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later. I skipped Gore Verbinski’s The Ring, which held little interest for me when it was released last fall; I was actually kind of surprised that Dreamworks had released the film on DVD so soon, usually when American film companies buy the remake rights to foreign films, they either bury or suppress the original (*cough* Miramax *cough*)

Ringu was a fairly tight movie, that created a nice sense of dread and tension throughout (aided by the helpful titles, telling you how much time the heroine had to live), and also generated some genuinely scary moments (stupid stinger music cues and expert framing); I generally appreciate horror movies that rely on suspense and craft, rather than gore, and Ringu was solidly a film of the former type. It’s unfortunate that five years of press in various film magazines had already ruined the twist ending for me, though it still was creepy in it’s own right, with Sadako slowly crawling out of the well, and then the television itself, to kill Ryuiji. I puttered around the Internet this morning to learn how the Japanese version differed from the American version (which was padded out with 20 additional minutes of footage); the backstory is definitely different, as well as Sadako’s motivations for killing. The Japanese version is also horse free, and seems more morally ambiguous (Sadako may have been a child, but she was also a psychic, possibly inhuman, monster).

Side Note In a recent AIM conversation, phyrephox asked me about “White Elephant Art,” a disparagement that some of us use on a frequent basis. Well, the term was coined by critical paragon Manny Farber in his seminal essay “White Elephant Art vs. Termite Art,”, which ironically, appeared in the same issue of the magazine Film Culture, as another seminal essay, Andrew Sarris’s "Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962.” Might as well post a link to the article, so that everyone can draw their own conclusions. Either that, or get your lazy asses to the bookstore or library, and rent Farber’s collection of essays Negative Space (another favorite Farber essay is “The Underground Film,” which has nothing to do with avant-garde film).

|