Hero

Zhang Yimou’s Hero, scripted well  before Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon but indulging in the Western success of that film ( Hero was given an astronomically high budget of $31 million, and was picked up for distribution and heavily edited by Miramax), is, in the director’s own words, a commercial film. To be more precise, Hero is a commercial action film, but Zhang does not forget his 5th generation roots of placing art-house allegory behind commercial narratives. Having accumulated what is probably the finest Chinese cast and crew seen in recent memory, Hero enlists the art-house talents of cinema’s most blissfully yearning on-screen couple, Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu Wai, as well as the talent of the finest working cinematographer today, Christopher Doyle. On the commercial side of things, besides for Miramax’s all too common foray into hacking their overseas acquisitions to pieces (this cut of Hero is roughly 30 minutes shorter than the original), are the martial arts legends Jet Li and Donnie Yen, along with fight choreographer Siu-Tang Ching who helped make numerous Tsui Hark film’s the classics they are today. The result of this unique bridge between Zhang’s world of formal art-house entries and the commercial viability of Jet Li wuxia is a distinctly philosophical, highly structured, and formally poetic action picture.

Nameless (Jet Li),  a warrior considered the finest swordfighter in the land, is summoned to the palace of the King of Qin (Daoming Chen). Qin’s tyrannical king is known for being the first ruler to unite the splintered kingdoms of China in the 3rd century B.C., and thus became the first emperor of China. A brutal Legalist who had a particularly bloody reign, the King’s policy of death and destruction to achieve peace and unification of All Under Heaven is at the thematic forefront of Zhang’s film (Hero’s tagline is “How Far Would You Go To Become a Hero?”). As Hero opens the King has yet to conquer all the kingdoms, but his tyranny is well known, as are his objectives for creating a vast empire. Nameless comes to the King to tell how he challenged, fought, and killed the three most deadly assassins in China, who were united in a mission to kill the King (a story sharing similarities to Chen Kaige’s The Emperor and the Assassin).

Nameless’ story is told three times, in three different ways through flashbacks, drawing from the Rashomon tradition. In the first, Nameless challenges and kills Sky (Donnie Yen) by fighting him mentally. He then proceeds to a famous calligraphy school where he tricks Broken Sword (Tony Leung) into sleeping with his assistant Moon (Zhang Ziyi), therefore cheating on Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung). Flying Snow kills Broken Sword out of jealousy, Moon challenges her and loses, and Nameless proceeds to defeat the now emotionally unstable Flying Snow. A simple tale of romantic melodrama with a dash of swordplay. Or is it? The King of Qin questions Nameless’ “petty” narrative and begins to look at Nameless’ own interest in assassinating the King. The King suggests in alternate story that the swordsmen make a pact so that Nameless could kill them and therefore be granted a personal audience with the King, and thus have an opportunity for assassination.

Hero functions as a surprisingly fitting combination of wuxia conventions and Zhang’s color-coded semiotics. The film is really just a series of epic showdowns between swordsmen, and as each flashback  tells a different story each duel is retold in a different context. To hammer this home, Zhang drenches every story in a different color, from the production design, to the costumes, to the lighting and camera filters. The confrontation between the King of Qin and Nameless is clothed in black, Nameless’ first story of melodrama and passion is blood red, the next retelling is of restrained sacrifice and is shot in cool blue, a flashback within the story to a time of youth is forest green, and the final retelling is of misunderstanding and love and is told in a nearly clinical shade of white. Behind these retellings are some subtle and not so subtle politics. There is a distinct possibility that a number of the five swordsmen in the film represent various extensions of the modern China state, namely Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Tibet, though a serious inspection into the allegory would require both several viewings of Hero as well as some brushing up on modern Chinese history. Along side this is the overarching theme of personal sacrifice for the state (or greater good), as the swordsmen decide to sacrifice their lives to kill the King, just as the king destroys kingdoms to unite the land.

Beyond its rather  simple but opaque narrative meaning, Hero is strictly formalized. The dense color coding, where the color of an actor’s costume, the background set, and the lighting vary only by minute shades is complimented by highly symmetrical compositions and rigid interior framing as a backdrop. In front of these Zhang poses his actors, who do little in terms of performances, opting instead for an unusual formalization of wuxia conventions, almost freezing each their characters as they strike this pose, which conveys this feeling or idea. Instead of being living, breathing people, the swordsmen of the film are emblematic extensions of specific values and expressions of feelings and nationalism. Thus the martial showdowns are clashes of ideals and emotions as expressed through swordplay (the duels take up considerably more screentime than the narrative itself) and the context for each duel is provided by the color themes of the film.

It is difficult to describe the fights themselves without using the clichéd terms first born with The Wild Bunch, continued by John Woo in the 1980s, and plastered to anything Yuen Woo-Ping does in the 90s, but Hero truly is the cinematic perfection of martial arts as visual poetry. While the fights work as fights, and are not, say, abstracted to mere formalism as in Wong Kar-Wai’s Ashes of Time, Zhang individualizes each showdown (exceedingly difficult considering the movie features the same fights repeated  several times in different ways) and focuses on how each fighter expresses themselves to their opponent through their motion and use of their environment. (While all duels specifically showcase their environments as part of the expression of swordplay, two in particular should go down in cinema history: one taking place deep in an autumn forest, where Flying Snow whips up the golden leaves coating the forest floor into a swirling flurry to assail Moon; and a heartbreakingly elegant touch-and-go duel between Nameless and Broken Sword, set on the unbelievably stunning Cold Bamboo lake in Sichuan, where they softly touch the surface of the water, propel themselves gracefully towards each other, touch swords, and return to the water.) This is strongly evidenced in the way Doyle and Zhang shoot the fights. Though they often give the actors the leeway of long takes to indulge in pure technique (though many of the actors have little background in martial arts), Zhang likes to cut on smooth movement. Surprisingly, most of the duels are as edited as heavily as Western martial arts bastardizations, but Zhang does it to layer movement, highlighting and building on graceful extensions of motion. The analogy of swordfighting as calligraphy is a theme of the film, and though it is hammered into our heads constantly, it is apt when Siu-Tang Ching choreographs each fight around smooth, interacting strokes and Doyle photographs it in dense, powerful colors.

Interesting, the foray into genre lets Zhang do action like he does all his other subjects, picking a typical, even simple story and coating it in sublime, often vague language of semiotics and colors. Hero has much in it to discuss, though the artful, exciting, and intelligent exploration of wuxia is far more interesting than the film’s somewhat stolid political allegory. Hero’s principle theme of sacrifice for the greater good and all that entails on a personal and national level is, if not a bit heavy handed, a bit too broad and plain to be successful. Actually, Zhang’s visual language is often broad and simple, but he masks it behind complicated and often impenetrable symbols and unusual associations, which lets the film flow visually with considerable grace, even if the narrative itself isn’t exactly compelling.

Notes on The Dancer Upstairs

Well, I was unable to log online yesterday, and through most of today, so I thought I would post some quick thoughts on the one movie I saw this weekend, John Malkovich’s (film) directorial debut, The Dancer Upstairs. Here was a film that I admired in some respects, but which did not stir any kind of passion in me, one way or another. The Dancer Upstairs, based on a novel by Nicholas Shakespeare, is one of those movies, like John Sayles’s didactic and schematic Men With Guns, that takes place in an unnamed Latin American country but which is based on actual fact. In this case, it was the pursuit of Abimael Guzman, the leader of the Maoist Shining Path movement in Peru, which terrorized the country from the late 70s to the early 1990s.

I have actually have mixed feelings about this type of approach; I understand that no movie perfectly depicts historical events, and that fictionalizing events makes them more dramatically pliable (while I’m not familiar with the details of Guzman’s capture, I doubt that the lead policeman fell in love with one of his zealots) and more universally applicable. However, the approach does sacrifice local detail, and more importantly, a specific historical-political context in which the action occurs. For example, even though the government is depicted as brutal, racist, and corrupt, we never learn what really motivates the followers of Ezequiel. They are described as Communists at one point (Ezequiel refers to himself as “fourth flame of Communism,” which I guess is a quote attributed to Guzman), but seem to engage in brutal terrorist acts and gruesome political theater (quite literally at one point; the Interior Minister and his wife are assassinated by a troupe of avant-garde dancers). This is definitely intentional on Malkovich’s part, as you can read here in this Onion AV Club interview where he rails against ideology, among other things.

Other than Malkovich’s moody direction (which is actually enhanced by the location shooting in Quito, Madrid, and Portugal and the gruesome, unexplained political theater), I might as well go with the strength of the film, which should be no surprise, is the acting (it’s certainly not the story, well at least for me, I was able to guess from the trailers I saw two months ago that Yolanda was one of the terrorists; this is not to say that Malkovich could not orchestrate suspense; check out the tense, drawn-out build up to the storming of Yolanda’s house and studio, punctuated by a bit of comedy, as Rejas’s wife appears to pick up his daughter, and then dallies outside, much to the frustration of her husband). Javier Bardem plays the lead character, Capt. Rejas, a policeman tasked with capturing Ezequiel. An intelligent, soft-spoken man, who along with the other policemen under his command, is given to dry gallows humor (at one point, after finding the dogs tied to lampposts, messages from Ezequiel, he quips that they shouldn’t “rule out cat lovers”). Rejas looks tired, the bags under his eyes being dragged down by a mixture of idealism and realism; I’d be tired too, not only does Rejas have to deal with terrorists, but also a military aggressively imposing martial law and a vain, self-absorbed wife (there’s a revolution going on, and she’s concerned with a nose job, her book club, and selling cosmetics). The backbone of the story is the somewhat leisurely developed, chaste relationship between Rejas and his daughter’s ballet teacher, Yolanda (Laura Morante), which ends tragically with the capture of Ezequiel, and the two, potential lovers learn each other’s true identities’.

The film’s penultimate scene is ambiguous. Despite his dislike of the government (he has a long, long list of grievances), Rejas compromises with them to insure better treatment and an early release for Yolanda, who refuses to even see or communicate with him. In return, Rejas is offered a position with the government, which he now must publicly support (Rejas’s capture of Ezequiel has propelled him to national prominence and popularity). Despite these events, the film actually ends on a positive note, as Rejas watches his daughter’s ballet recital. A bittersweet moment (Rejas arrives late, and watches from behind some glass doors; when his wife notices his presence, she turns and winks at him), but one that looks towards the future.

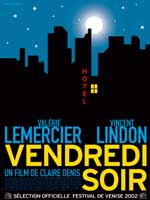

Friday Night

As Friday Night opens the sun slowly sets on Paris, first touching, then burning,  and finally extinguishing the enchantingly cluttered skyline. The opening minutes of the film, which are as cinematically leisurely as possibly, as well as supremely concise in its content, speaks well for the rest of Claire Denis’ new film. Helping adapt the novel by Emmanuèle Bernheim (who also co-wrote Ozon’s Swimming Pool and Under The Sand), Denis proposes to photograph with a loving patience the buildup and climax of what amounts to a one-night stand between two strangers. Practically devoid of context, Friday Night only admits that Laure (Valérie Lemercier) is in the process of moving out of her own apartment and into the apartment of another man, who she will meet Saturday morning. On the way to dinner Laure gets stuck in a traffic jam that is backing up all of Paris, and after endlessly inching forward and getting nowhere she offers a ride to a handsome man named Jean (Vincent Lindon). Laure, sleepy from the car’s heater, dozes off and when she wakes she seems to have acquired an understated desire for the stranger she let into her automobile. After some unusual flirting (Laure puts her car in Jean’s hands, and he proceeds to blindly speed through Paris, the traffic jam a distant memory), the two soon advance their relationship to a nearby hotel.

With only the juicy but ambiguous knowledge that Laure is (literally) in a state of relationship flux, Denis and her two handsomely middle-aged leads give little, if any, hint of motive to the affair. Denis’ masterful DP Agnès Godard gives even the interminable traffic jam (which lasts a good deal of the film’s lengthy 90 minutes) a spectacular  luster, finding beautiful gloss in the stationary automobiles; later in the evening she adds subtle dashes of neon to the palette and enough muted green and burgundy to make Friday Night speak in a predominantly visual vernacular, though it never feels like Godard r Denis are ever trying to romanticizing the images. (In fact much of the film recalls Wong Kar-Wai’s In The Mood For Love sucked of dizzying quixotic context and robbed of a camera all too eager to give every movement its romantic benefit of doubt.) It is doubtful that Denis expects one to approach her film analytically, whether one is questioning vague morality or ambiguous motives, and the practically wordless film, with its fluid jump cuts and preference for lingering on every single minute of the evening, feels like one is watching a slow burning cigarette: gentle, simple, beautiful, but a little wearisome.

The languid portrayal of Laure’s evening coupled with the sexual spontaneity of her affair with Jean gives Friday Night an unusual quality of smoldering predictability. There is little doubt that Denis has perfectly captured much of the essence of one-night stands-the pleasure in little moments, ambiguous shared sexual understandings, and the comfortable claustrophobia of confining environments (the principle action is closeted off in a car, a hotel, and a restaurant)-but what feels special between the leads isn’t necessarily  special for the audience. Laure and Jean’s union looks beautiful enough, but it seems that Denis’ priority is more to capture the gentle impulsiveness of a long evening than to subjectively allow the audience to access the world of the two lovers. Like Denis’ masterpiece Beau Travail, Friday Night works more as a distant, elliptical cinematic poem than an involving narrative yarn. Brief moments of startling anxiety, as when Laure leaves her car in the middle of traffic to make a phone call and returns to find the car gone, help to make some of the film’s rather monotonous (if lovingly crafted) cinematic stanzas differ. This sporadic tone change helps give the film a whiff of occasional genre intrigue, or at least conventionality. When coupled with the beauty of the film it is enough to give Friday Night some element of passion, something sorely, but purposely, lacking from much of the experience of the film. It is never quite interesting or exciting enough, for it always seems to lack a spark of passion, and yet strangely, and to Denis’ credit, Friday Night remains utterly convincing.

A Note on Adaptation

OK, so my movie-watching has fallen off and I've just seen the DVD of Adaptation. I won't bore you with my thoughts on it's general brilliance or intricacy or what it all means, as the subject has likely been picked over. One question though: has it been noted or remarked anywhere that the film owes a debt to Sam Shepherd's play True West -- not literally, but in terms of inspiration, perhaps? Great play about a semi-successful screenwriter whose brother is a scummy low-life burglar. Over the course of the drama, the two men gradually switch personalities; the burglar has a screenplay idea which turns out to have more currency than his brother's, and turns into a Hollywood bigshot of sorts, while his presumably smarter sibling takes a personal nosedive and ultimately turns to robbing houses. Been years since I've seen it, so I've forgotten a lot of the plot. The role of the burglar, incidentally, was first played by John Malkovich; the other was Gary Sinise. Anyway, it came to mind.

P.S. Just Googled "True West" and "Charlie Kaufman." Ninety-one hits, and it looks like I'm not the first to make the connection: "closely echos Sam Shepard's play, True West," "a hint of Sam Shepard's True West," "the screenwriters-as-doppelganger idea felt straight out of Shepard’s TRUE WEST," "suspiciously derivative of True West," etc.

Trouble in Paradise

Trouble in Paradise, 1932. Ernst Lubitsch's pre-Code masterpiece about a playboy jewel thief torn between his wealthy, widowed mark and his pickpocket lover.

The film begins with a sequence that intercuts between two rooms at the same luxury hotel in Venice, Italy. In one room, the Royal Suite, M. Filiba has been assaulted by an unknown attacker, and is telling his story to the hotel detective and the police. In the other room, a Baron is having a romantic dinner with a Countess, who is nervous about her reputation, dining alone with a man in his room.

Over their private dinner, the Countess (Miriam Hopkins) casually announces that she knows that the Baron is the man who assaulted M. Filiba – then politely asks him to pass the salt. The Baron (Herbert Marshall) returns just as casually that the Countess is a thief, and he knows that she swiped Filiba's wallet from him: "In fact, you tickled me." In the scene that follows, the two trade back the items that they have stolen from each other in the previous few minutes – a watch here, a jewel there – until the climax, when the Baron produces her garter from his pocket, kisses it, and then puts it back in his pocket, to keep as a souvenir. The Countess is delighted, and throws herself into his arms.

It's clear from this moment that these two are made for each other. The Baron is actually Gaston Monescu, world-renowned jewel thief. The "Countess" is Lily Vautier, a common pickpocket among a rather uncommon crowd. Together they embark on a high-class crime spree across Europe. Sort of an early Bonnie & Clyde, except they don't kill anyone. That would be distasteful.

One year later, Monescu and Lily are still very much in love, but in need of a bankroll. They find their mark in Mme. Mariet Colet (Kay Francis), the wealthy widow of a perfume tycoon. Mme. Colet has inherited the perfume company but has no head for business, and her casual appearances at board meetings only serve to frustrate the executives. She would much rather be out shopping. She is also being pursued by two gentlemen: The Major (Charlie Ruggles) and good ol' M. Filiba (Edward Everett Horton), but she's not really interested in either of them.

Monescu and Lily at first only intend to steal Mme. Colet's highly-overpriced handbag, but when they discover who she is, Monescu (as M. LeValle) insinuates himself as her personal and business secretary (with benefits) – with a plan for the big score -- $80,000 francs.

Complications arise when Monescu finds himself becoming romantically involved with Mme. Colet, which not only incurs Lily's wrath but also interferes with his plot to steal the money. Not to mention the fact that M. Filiba finally remembers where he met M. LeValle in the first place.

Much has been written by film critics and historians about Ernst Lubitsch and "The Lubitsch Touch." His influence can be seen very clearly in the works of Billy Wilder and Preston Sturges and several directors even up to today.

It's difficult to put your finger on exactly what sets Lubitsch apart, and above, other directors of his time. He was very devoted to the writing – not just the dialogue, not just the plot, but the structure and the shape in which the story unfolds (Lubitsch co-wrote most of his scripts, but rarely took credit). But he was not rooted in the script, either; Lubitsch understood that film is a visual medium (having gotten his start in silent films), and knew how to let the camera tell his story as well, rather than put it all in the mouths of his characters.

Lubitsch's comedic style was to take a joke or a humorous situation, play it for all it's worth, then, just when you think it's played out, toss in a capper. Take for example the dinner scene between Monescu and Lily, where they return their stolen items to each other: Most directors would stop with the jewel and the watch, but Lubitsch goes one step further with the garter – and turning the joke on its ear, Monescu doesn't return it; he kisses it and puts it back in his pocket. This too is characteristic of Lubitsch – his handling of sexuality with frankness and humor.

Visually, Lubitsch was a master at transitionary montages, in which exposition and the passage of time could be whittled down to a few seconds. In Trouble in Paradise, the introduction of Mme. Colet takes only a few moments, through a montage of various people (maids, butlers, shopkeepers, chauffeurs, gardeners) saying either, "Yes, Madame" or "No, Madame." We know everything we need to know about her from this: she's rich, she likes to shop, and she's used to getting her way. Later, when Monescu moves in and takes over her business, the scene is repeated: "Yes, Monsieur," and "No, Monsieur."

Lubitsch also had a knack of getting uncharacteristically good performances out of his actors. Herbert Marshall, a staid and rather bland English actor with no sex appeal whatsoever in any other film of his I've seen, positively crackles with sly sexual energy in Trouble in Paradise. Miriam Hopkins and Kay Francis, extremely talented and attractive actresses to begin with, both have a sparkle in this film unmatched in the rest of their repertoire. Toss in Charlie Ruggles and Edward Everett Horton, two of my favorite character actors from the '30s, and you've got a winner.

Beautifully restored on DVD from Criterion – pricey at forty bucks but well worth it.

The Mother and the Whore

Spider,

The Mother and the Whore

Spider, the latest film from David Cronenberg, is Psycho on Prozac: a strange, slow, moody drama about a deranged man with a mother fixation, and it may not begin to work on you until after it's over. It takes a long time getting started, and that does work against it a bit; about 20 minutes in, a guy in back of me muttered "So far I'm enthralled" to his wife, who I suspect dragged him to see it. "Shut up," I muttered, but I could kind of see his point, as I was doing a little seat-shifting as well. Cronenberg wants to put us in the drab, hazy, suffocating world of his lead character, Dennis -- played by Ralph Fiennes, doing his studied level best to create another kind of English patient -- and he sacrifices little to audience comfort.

Dennis has just been released from an asylum into some kind of a group home for the aged or mentally ill, run with an iron hand by a stiff-backed Nurse Ratched type with a menacing perm (Lynn Redgrave). We don't know much about Dennis except that he has some sort of deranged obsessive-compulsive disorder: he mumbles incoherently, writes unreadable scribbles in a notebook which no one could possibly read but which he carefully hides anyway, wears four or five shirts at the same time, uses twine to weave a web in his room, and is clearly tortured by something in his past we can't quite fathom.

The past kicks in. The adult Dennis begins recalling scenes from his childhood, and rather literally wanders about in them: a deranged, unshaven, ill-kempt sod watching his well-groomed and proper eight or nine year old self from 30 years earlier. His home life growing up is one of those dull, sad, working-class English ones, where his long-suffering, slightly dumpy mother (Miranda Richardson) sends him the grimy local pub to fetch his grumpy, put-upon dad (Gabriel Byrne); while he's there, a low-life tramp viciously bares her tit at him. As scenes of home are played out, Dennis -- nicknamed "Spider" by his mother -- watches the up and down cycle of his parent's marriage: squabbling and making up; fighting and then later having a night on the town. A patchy story emerges, of a loving mother who is trying to hold her family together despite the wandering eye of a blustery, bitter dad. Suddenly the past, in Dennis's reconstruction of it, takes a hairpin turn: his dad kills his mother, and brings home a tramp who looks a good deal like the one Dennis saw in the bar, only this time she is played by Miranda Richardson.

The story, of course, now looks shaky, as the dad simply buries the mother's corpse with the help of his new girlfriend; there's nothing rational about this memory, no report of a missing person or police involvement. As Dennis remembers it, his dear mom was merely killed by his bastard father and replaced by an ill-bred cockney slut with bad teeth.

Of course, there is more to it than this, and the challenge of watching it is figuring out just what the "real" story is, of separating Dennis' real memories from his false one, the one which he has constructed, like a spider's stratagem, as a psychological self-defense. I'll confess I didn't really, really get the whole story until I had coffee this morning and was replaying it in my head, at which point I recalled a key scene. I'm thinking of going back tomorrow evening before it leaves town to see if I had it right. It's the kind of torpid film which probably improves on a second viewing.

All this is, of course, right up Cronenberg's alley, who does a typically good job at putting you in a dislocated world, this time focusing constantly on feet, as if even the adult Dennis is still seeing things from a child's-eye view. Miranda Richardson, in the dual role, does her usual excellent job. I was less impressed with Fiennes. You know how mental patient roles go: there are two kinds, ones where you forget the guy is acting, and ones -- like Fiennes' -- where you couldn't forget if you tried. He has the wild eyes and the involuntary breathing down, but the story moved me more than he did. The real points here go to Patrick McGrath's script (from his novel) and the slow build of Cronenburg's pacing, which does, indeed, enthrall. It just takes its sweet time getting there.

|