A Brief History Lesson

Recently, I heard the phrase, “Before Hollywood, there was Fort Lee.” Definitely true, and there exists a rich history of Fort Lee productions, but it's not the whole story. Growth during the infancy of the movie industry mainly came from population centers, leading to several cities sporting home-grown studios. New York had some of the best-known, including Biograph, the studios of Fort Lee, some locations in the Bronx, and Edison’s studio in New Jersey. Chicago had Essanay. New Rochelle had Thanhouser. From 1912 to 1922 Philadelphia had the Betzwood.

Every year, Montgomery County Community College in Blue Bell, PA, which houses the Betzwood Archive, hosts the Betzwood Silent Film Festival. From this year’s program:

Founded by film pioneer Siegmund Lubin in 1912, and later owned and operated by Wolf Brothers, Inc., of Philadelphia (1917-1922), this studio was the production site for over 100 films of various genres. With both electric and daylight stages, its own power plant, and a complete processing laboratory, the 350 acre studio was world famous as one of the largest and most advanced studios of its time.

The Betzwood Festival showcases the studio's productions, tracked down in archives around the world. Although not the polished gems of the late twenties, the Betzwood films are a great look into early filmmaking techniques and practices outside of the established leaders. The Drunkard’s Child (1909), restored from a paper print in the Library of Congress, is a simple morality tale of strung-together vignettes with all action spelled out through the intertitles. Three years later, The Physician’s Honor (1912), starring Arthur V. Johnson and Ormi Hawley (two of the earliest movie stars), unspools a more complex narrative - again morality-based - but still leaves nothing up to audience interpretation. The Price of Victory (1913), a story of honor and sacrifice among southerners, is a little more sophisticated, allowing the audience to pick up hints rather than spoonfeeding them. The film also moves beyond pure narrative, featuring authentic Civil War uniforms, equipment, and artillery. (The curator conjectured in a side conversation that Lubin featured Confederate stories in so many of his Civil War films - shot around 50th anniversary commemorations - for the simple reason that he had more Confederate uniforms at his disposal.)

A Girl’s Folly (1917), the festival feature, was out of the Éclair Studio in Fort Lee but is the most instructive of the set. The movie is about a young woman in rural New Jersey (! - New Jersey definitely doesn't look like that anymore) who dreams of adventure and runs into it when she stumbles across a movie set in her back yard. She ends up in The Big City (New York) to try her hand in the movies. The acting is bright, the story is amusing, but it’s the moviemaking scenes that really set the film apart. The director calls for a bedroom – the workmen set up the walls, lay down the carpet, movie in the furniture and within five minutes there’s a bedroom. The angle looks wrong? Rotate the stage 90 degrees until the light is right. Then come the actors. The extras make themselves up in a common room; the star gets his own dressing room with valet at his elbow and yesterday's girlfriend trying to catch his eye. The actors laze about and horse around with each other until time for their scenes. On the set, the director tells each character what they’re supposed to do because, as the intertitle tells us, “Frequently, ‘movie actors’ do not know the plot of the picture in which they are working” (Mike Leigh has nothing on them). There are the constant retakes, the noise of several other productions filming at the same time, the assembly-line structure of the editing room - but there’s also the camaraderie of the commissary, support from friends during the big screen test viewing, the party atmosphere of going on location. Is it surprising that the girl decides to stay on with her new movie friends after her failed screen test?

The darker side of the movie life also comes into play – or at least follows the stereotype: the valets and maids, expensive cars and fancy clothes, the implication of a “kept” woman, the parties that degenerate into things too risque for 1917 audiences. The girl ends up “saved” by a mother wielding a birthday cake; but more importantly, the movie is an early entry in a whole genre of “life in Hollywood” movies, including such notables as The Last Command, Show People, All About Eve, A Hard Day’s Night (remember the scene in the commissary with Ringo and Paul’s granddad), and The Player. Altogether a fascinating look at studio life.

Question of the Week

Here's the flip side of the last question of the week. Just like the modern city, epic vistas have been a staple of cinema since it's inception, so we are heading out of the city and into the wilderness. Well, not just the wilderness, because I've decided to lump in small towns and rural areas into the equation. So, the question of the week is:

Name a movie which best represents a particular landscape and/or rural area. What about the film captures the essence of the landscape and/or rural area in question, and how does the filmmaker(s) utilize that "essence" for expressive purposes?

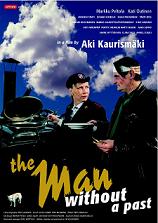

The Man Without a Past

A gangly, worn-out looking man falls asleep on a park bench, resting against his sole suitcase after a long night of traveling on by train. As soon as this anonymous stranger nods off a group of young punks jump him, and by the time they finish their beating the man has just as clear an idea of who he is as the audience does. Resurrected  by an unseen power in a hospital after flatlining, the man stumbles down to the docks of Helsinki, passes out and is nursed back to health by a poor family. Given an unusual second chance to make something of himself, the man embraces his anonymity and allows himself to be absorbed into the lower class life of the people living near the docks. Even his name a mystery, living in near poverty with only the clothes on his back (donated by the Salvation Army), and amongst total strangers this man, with remarkable dignity, quickly builds a respectable existence by moving into a large metal crate, managing a rock and roll band, wooing an Army worker and distributing funds for a bankrobber.

Regardless of its bleak opening minutes, Aki Kaurismäki’s The Man Without a Past carries itself with a levity and effortlessness embodied in the mystery man’s enviable and bafflingly positive outlook to his life of anonymity in industrial, lower-class Helsinki. Part of the film’s charm is that even in its simplicity (man loses memory, builds new life) the mystery man’s unique situation allows Kaurismäki to delicately combine such a strange variety of genres one would think the film would appear over packed. Part romance, part comedy, and part Finnish kitchen-sink social drama of the lower class, Kaurismäki’s plot even echoes strongly of American noir conventions, complete with an amnesiac hero, a cold blonde and the impoverished Helsinki equivalent of a slinky nightclub complete with a smoky female singer.

Labeled as “M” by the end credits, the film’s mystery man is played by Markku Peltola, who is as lanky, broad shouldered and physically extended as Liam Neeson and as barrel-chested as Robert Mitchum, but has a quiet, carefully articulated talent for physical comedy in slight gestures, as well as possessing one of those well weathered faces that perfectly compliments deadpan comedy (somewhat along the lines of Takeshi Kitano, but far kinder). Besides for Peltola the most intriguing face in the film is that of Kati Outinen,

who plays Irma, the Salvation Army worker who M gradually and tenderly courts. Despite her relatively small amount of screen time Outinen won Best Actress at Cannes, and it is easy to see why when a simple, single head movement from the actress can speak wonders about how she truly feels about M’s advances. Peltola’s introduction in the film, wordless until he recovers from his injuries, is representative for almost all characters in The Man Without a Past in that it illustrates Kaurismäki’s admirable talent for casting actors who’s faces usually speak more for their characters than their dialog does; this talent allows Kaurismäki to focus on far more interesting details in the film world, from Peltola’s ridiculously stiff walking strut to the delicate colors hidden around the industrial detritus of the docks. That’s not to say Kaurismäki’s script is lacking, in fact it builds an undercurrent of slight comedy so covertly that one watches the movie from the vicious beating at its beginning to the first laugh out loud moment twenty minutes in and not realize there was a tone change.

Lovingly scattered inside The Man Without a Past, along with the quiet romance between M and Irma at its center, are a number of thematically strange but atmospherically perfect minor digressions, centering on the group  of people who live in various poor shelters down by the docks (these ranging from the small metal storage container M lives in to garbage dumpsters). Kaurismäki uplifts the dreary setting of the film with a mise-en-scene lightly coated in pastels and other kinder colors that help bridge the gap between the pleasant attitudes of the cast and the relatively poor local they in (at a poverty level where dinner at the Salvation Army is considered a Friday night out). Coupled with the delicate colors is a pleasant breeze of absurdity throughout the film, one which also tends to reflect the split between the very friendly and content attitude of the Helsinki characters and their rather poor material existence. Such quietly absurd deviations are exemplified when M uses his free time to turn the Salvation Army’s religious choir into a Finnish rock and roll band that understandably stirs more elation from the people than God ever did.

In what must be a first for the amnesia film genre, M seems to have no real desire to find out his identity, though he is often frustrated by his memory loss-without a name he cannot file for a legitimate job or real housing. With no plot to push The Man Without a Past firmly along, other than Irma and M’s slow relationship, the narrative gently sways forward and back and enjoys lingering on the tragicomic of M’s situation and his friends. Such a creative mildness in the film’s tone helps make up for relatively little conflict in The Man Without a Past; with  a lack of any past events to base future decisions on, M seems to effortlessly overcome all obstacles placed in his path, easily acquiring employment, easily finding a home (he decorates his metal crate with a jukebox and leather lounge chairs), easily finding a soul mate and eventually stumbling into his identity. The lack of a serious threat to the heroic lead, with the obvious exception of his brutal assault that opens the film, provides the film with a lovely nostalgic, old fashioned atmosphere, what with M’s slow and traditional wooing of Irma, carefully placed cars and music from the 60s, and the touchingly carefree attitudes of the destitute people who live around M. It seems fitting that because M is missing his memory The Man Without a Past exists in a strange timeless bubble of near inaction, where the film’s inhabitants seems to take pleasure in just being, where there is no clear time or space other than the isolated plebeian dock community, and the slight absurdity of everyone’s positive attitudes are the base of much of the film’s marvelous deadpan comedy. Such a small, ingenious, quietly affecting film could probably be easily labeled as evidence of second coming in Scandinavian cinema if Kaurismäki was not already known for making movies such films for the last decade or so. But, probably due to its winning the Grand Jury price at Cannes, this is his first film to get significant distribution in the States, so hopefully the film will open the doors for a cinema that has generally been closed to American audiences since Bergman stopped working.

Sunday Wrap-Up

So many movies (at least this weekend), and so little time, especially with two, count’em two, hours of Alias tonight (and I have been consistently distracted by cable airings of Unforgiven and Four Weddings and a Funeral). Saw four films this weekend, and since I’ve already talked (at length) about Grin Without a Cat, I’m going to concentrate on some short reviews of the other three movies, All the Real Girls, Spider, and Lady Windermere’s Fan; that, and I might as well write a bit about a film that I saw last weekend, Eloge de l’amour/In Praise of Love.

All the Real Girls (d. David Gordon Green)

I missed George Washington when it came to the theaters, and I still haven’t got around to watching it on DVD, so this is my first experience with a David Gordon Green film. The Terrence Malick comparisons are apt, and All the Real Girls had a Days of Heaven sort of vibe (though the films really have little in common). All the Real Girls is a paradox of a movie: naturalistic, yet dreamlike; a decaying autumnal/wintery post-industrial Appalachian landscape rendered incredibly beautiful by the camerawork of DP Tim Orr; and characters who are both inarticulate and real, yet speak in such a precious, poetic, singular way that is not cloying, but is strangely, and emotionally, appropriate. The story is deceptively simple, a small town lothario falls for his best friend’s younger sister; in a karmic twist, her drunken indiscretion leads him to feel both real pain and real love for the first time. Simply put, I loved this movie. It had it’s own particular rhythm and tone, the love story, which in a somewhat unusual choice, begins in media res (so no meet cute, or build-up), was sweet, while the subsequent break-up and attempts at reconciliation were both painful and frustrating. One of the more unique looks at young love I’ve seen in quite a while.

Zooey Deschanel, with her big eyes, and slow, low-pitched drawl of a delivery, vaulted to the top of my list of young, indie actresses/goddesses, alongside Maggie Gyllenhaal.

Spider (d. David Cronenberg)

Not much more that I can contribute to at this moment; I liked the film, liked it a lot, by I’m going to shy away from the more effusive praise heaped on the film by such critics as Amy Taubin. I don’t think that Spider is quite to the level of Cronenberg’s last two films, the auto-erotic masterpiece Crash, or the hilarious and gross mindfuck, eXistenZ. For one thing, the film lacked the the humor of his last two films. Otherwise, the film has pretty much what I expect from a Cronenberg film, with the exquisitely controlled color palette and mise-en-scene (I especially liked the opening credit sequence, with its repeated views of demon-like Rorschach Blots). In many ways the anti- A Beautiful Mind, the film blurs the lines between objective reality and the subjective, actually delusional, memory in which the Oedipal drama of Spider’s life is played out, without becoming overblown melodrama or some kind of Hollywoodization of schizophrenic delusion, reality and delusion are as equally controlled, which is the way it should, since Spider experiences one as the other (though the line is clear to the audience, not only with Miranda Richardson playing two, and later three, roles, a direct embodiment of the Madonna-Whore complex, but with the adult Spider witnessing events that he was not present at). The whole thing is quite chilling.

I was impressed with Ralph Fiennes incredibly internalized performance (as possible the best looking schizophrenic since Patrick Dempsey’s role as Uncle Aaron in Once and Again), which consists of mainly mumbling to himself and looking haunted. Miranda Richardson did double, no triple, duty convincingly playing two intentionally stereotyped roles, the upright matron and the grotesque tart. Of course, both roles shade into each other.

Lady Windermere’s Fan (d. Ernst Lubitsch)

The final Cinematheque screening of the semester did not go on without a hitch, first there was a vigorous discussion on how fast it should be projected (for anyone interested, it’s 23fps, meaning that if you rent this on video or see it at the theater, if the film is less or more than approx. 85 minutes, you’re getting screwed), and second, there was a projector breakdown, forcing the projectionist to stop the film several times. I felt sorry for the pianist who accompanied the film. Even with these difficulties, I was glad to see the film, Ernst Lubitsch is absolutely one of my favorite directors, ever, so I jumped at the chance to see this 1925 film, despite some negative things I have read about it over the years, mostly from people who are unable to comprehend how a silent film could duplicate Oscar Wilde’s verbal wit. Well, Ernst Lubitsch is that man, and his translation of the play to the screen gives further credence to what I call my “ Throne of Blood/Ran Theory of Adaptation,” which basically states when adapting a play for a film, throw out just about everything. Lubitsch shows his mastery throughout the film, a comedy of manners/farce set in contemporary, aristocratic London, which ostensibly stars a young Ronald Coleman as the rakish Lord Darlington (though his is a secondary, supporting role). Lubitsch conveys all through his careful usage of mise-en-scene and cutting, never has so much been said through a slightly arched eyebrow or pouting lip and an eyeline match (yes, I’m treading into hyperbole), or by Lubitsch usage of montage and space (one funny gag has a suspicious Lady Windermere trying to break into the locked drawer of her husband’s desk, unable to do so, she calmly exits stage right, only to suddenly leap back into the frame from the left). Lubitsch continues his usage of props and behavior to suggestion overt sexuality, the two parallel visits of Lord Augustus to Lady Erlynne are excellent examples. A highly recommended film, not only to Lubitsch fans but any fan of Lubitsch in general.

I’m pausing, the reading of WH Auden’s poem in Four Weddings and a Funeral is just beginning....

Eloge de l’amour/In the Praise of Love (d. Jean-Luc Godard)

Godard’s controversial latest, though the controversy is mostly misplaced. While Godard is critical of America (I can’t decide if it is fair or unfair criticism in regards to Americans and history, Americans perhaps more than anyone else, live so much in the now, we do appropriate other’s histories for our own purposes, and we are often retards when it comes to the subject), unless your last name is Spielberg, there’s no reason to get angry (bad timing, given the context of it’s initial release post 9/11). Eloge de l’amour is an essay film, and I guess it can be described as difficult, it certainly doesn’t have much in the way of a narrative; it’s divided into two parts, an initial sequence shot in lustrous black and white, and consisting on various musings on love, art, history, and memory, as the characters attempt to cast what appears to be a film. The second part, shot in color on digital video (with a result that Godard, at several points, digitally manipulates the color for expressive effect) details a man, who appears in the first part of the film, as he attempts to write a cantata about the experiences of a couple who served in the Resistance, while a bunch of crass American film executives try to buy the writes to their story for Spielberg. The film is dense and elusive, and all but demands repeat viewings.

Something that I would like to point out, however, is Godard’s continued brilliance when it comes to the usage of sound, I only wish more filmmakers would utilize the soundtrack in such expressive ways. In Eloge de l’amour, Godard’s usage of disjunctive sound (characters speak from outside the frame, with their backs turned to the camera, over scenes where they are not physically present, or over black frames) caused me to pay much more attention to the soundtrack, and it’s relation to the visual image, just proving how interdependent our sensory modalities really are, and how our viewing experiences change when the sound and visual tracks are not anchored together in a strict way.

My New Favorite Commercial

Well, I have to say, I’ve only seen it once, but it has superseded all others as my favorite commercial. What am I talking about? Why, the new American Express commercial featuring Martin Scorsese at the photo mat. Oh my god, it’s hilarious, his best cameo/appearance since his walk-on in The Muse.

|