Grin Without a Cat

Who knew that a three hour documentary, largely about French left-wing politics could be so fascinating? Tonight was the penultimate Cinematheque program for the semester, a screening of Chris Marker’s documentary

Grin Without a Cat/Le Fond de l’air est rouge. Though originally released in 1977, Chris Marker revisited the film following the fall of the Soviet Union in 1992, rereleasing the film, slightly reedited, and featuring English-language narration (courtesy of Jim Broadbent and Cyril Cusack), in 1993 (the newer version was screened tonight). The film is a somewhat nostalgic, as well as critical look, at the rise and fall of what came to be called the New Left in France, during roughly a ten year period between 1967 and 1977 (though the film encompasses events from both before and after that period), using the epochal events of May 1968 and it’s immediate aftermath as the fulcrum between the film’s two 90 minute parts (the film’s French title, which is apparently untranslatable, was a student protest slogan in May 68). The first, entitled “Fragile Hands,” (the name of this part is from a placard slogan “The workers will take the struggle from the fragile hands of the students.”) follows the rise of the New Left out of leftist schisms and sentiments crystallizing around anti-imperialist/liberation movements, the most prominent being the war in Vietnam. The second “Severed Hands,” details the fall of the New Left due to a variety of factors: direct repression, often by the twin imperial hegemonies of the United States and the Soviet Union; the real nature of the Cultural Revolution; traditional Old Left movements forsaking revolutionary politics for democratic control; factional infighting (from the Left, get out of here!); and the actual institutionalizing of New Left elements (exemplified in the film by the progress of the revolution in Cuba).

Chris Marker is probably best known in the US for his 1962 short, photomontage film

La Jetee (which was the basis for Terry Gilliam’s

Twelve Monkeys), but Marker has had a long and varied career as a filmmaker, photographer, videographer, poet, journalist, multimedia artist, and designer. Along with Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, Marker was a member of the “Left Bank” group of filmmakers, whose work was contemporaneous with and even preceded that of the

nouvelle vague (Richard Roud coined the phrase “Left Bank” filmmakers to differentiate Resnais, Marker, and Varda from the better known

Cahiers group; the term referred not only to what side of the Seine the two groups lived-on, but also their political orientation, in the 1950s and early 1960s, the

Cahiers group was associated with political conservatism, with a few exceptions, such as the openly Marxist Pierre Kast). During the events of May 1968, Marker founded one of the more famous cinema collectives, SLON (

Societe pour le Lancement des Ouevres Nouvelles; a glimpse of a SLON film can be seen in Olivier Assayas film

Irma Vep), and participated in the cinetracts movement with Godard and Resnais (these were 16mm leftist newsreels about workers and students during May 68). However, filmmaking-wise, Marker is usually associated with the mode of documentary filmmaking called the essay film.

Grin Without a Cat is an example of such a film, creating an openly rhetorical essay out of various found footage (fiction films such as

The Battleship Potemkin, newsreels, archival footage, interviews, documentaries, etc.) For Marker, while the events of May 1968 are certainly momentous (for anyone not familiar with the events of May 1968, a coalition of student groups and workers staged a series of protests and strikes that seriously threatened De Gaulle and Fifth Republic; May 1968 is also a watershed event in film history: the increasingly radical

Cahiers du Cinema openly embraced Maoism, and began the introduction of radical politics, Althusserian structuralism, and Lacanian psychoanalysis to film theory; the 1968 Cannes Film Festival was canceled in support of the protests; several directors, such as Jean-luc Godard became quite radical, disrupting the uneasy camaraderie of the New Wave; the controversy surrounding the attempt by the French government to replace Henri Laglois as director of the Cinematheque Francais earlier in 1968 was seen as a precursor to the events of May 1968), he clearly sees that the birth of the New Left, as well as the seeds of it’s destruction, began earlier, during the growing protests of 1967.

For Marker, the New Left encapsulated an attitude expoused by Mao during the Cultural Revolution, of bringing a “revolution within a revolution.” The New Left forsook the the traditional Communist Party apparatus, as well as the traditional Union Leadership; instead of waiting around for dialectical materialism to work it’s magic, the forces of the New Left believed in direct, revolutionary praxis in order to set up a real Socialist Democracy (looking both to the Cultural Revolution and the Prague Spring as models, as contradictory as that may sound), as opposed to the Stalinist sham. This new praxis took the form of openly supporting guerilla movements in Third World liberation movements, as well as confrontational street protests in Europe and the United States. The confrontational, revolutionary fervor was in direct conflict with the older, established order, even if they were Marxist-Leninists (the English title, an obvious pun on the Cheshire Cat, is in reference to the death of Che Guevara; a US military advisor is asked by an interviewer what was Che’s biggest mistake in Bolivia, his answer was that he did not have the support of the Bolivian Communist Party; cut to an interview with the Bolivian CP Party Secretary, who was content to wait for the contradictions of capitalism to express themselves; this entire exchange prompts the cryptic commend “a grin without a cat,” or lack of support). The biggest rallying cry of the New Left, internationally speaking, was the war in Vietnam, which was compared by several interviewees in the film as the current generations “Spanish Civil War,” (they also compared the Cultural Revolution to the Russian Revolution of 1917).

Though the film is made-up of edited together footage (much like another favorite Leftist documentarian and kindred spirit, Emile De Antonio), Marker weaves it together in an expressive way, using both sound and image, sometimes together, other times disjunctively, to create a kaleidoscopic impression of the rapidly changing political landscape of the late 1960s and 1970s. Almost immediately, Marker draws a connection between the revolutionary fervor and idealism of the New Left and that of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (before it curdled into Stalinism). The film begins with a meditation on a key scene from Eisenstein’s

Battleship Potemkin, where one of the sailors shouts out “Brothers!,” before cutting together scenes from the Odessa Steps sequence with contemporary footage of various State Security Services violently repressing protests. Marker usage of montage is exemplary in this regard, the interpolation of new footage is almost seamless, as he uses a combination of graphic matches, eyelines, and cuts on action to draw explicit the parallels between contemporary and Czarist repression (scenes of police/military forces squaring off against protesters is common throughout the film).

Battleship Potemkin is a running motif in the film; as the events of May 1968 begin to unfold, and revolution appears to be sweeping through France, Marker cuts to the famous shots of the three lions rising from

Potemkin, later in the film, during the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia later that year, a bunch of Czech’s berate a young Russian tankdriver, and Marker cuts again to the “Brothers!” scene from

Potemkin.

Vietnam is certainly the highest profile event motivating the New Left, and it’s the first to receive serious attention. In one sequence, an USAF pilot is filming some sort of movie during a sortie, and gleefully talks about dropping napalm on “Victor Charlie;” as the pilot’s voice-over narration continues, Marker cuts to gruesome shots of badly burned and scarred napalm casualties. Easy points, I know but effective. More troubling is a scene from an American anti-draft protest. As a minister and a crowd of students protest the draft, youthful members of the American Nazi Party, wearing swastika armbands, counterprotest. One of them tries to articulate a position of repatriating “Negroes” to Africa, before they all begin chanting “Bomb Hanoi,” a few beats later, Marker cuts to a large group of American men, obviously business men, gleefully chanting the same slogan “Bomb Hanoi.”

A major point of interest in the film is in various guerilla insurgencies in Latin America, in particular Venezuela and Bolivia, none of which are supported by the indigenous Communist Parties, which would be a point of contention with factions of the New Left. Cuba is seen as the major proponent of New Left revolution/liberation ideology in Latin America, as they were the ones who supported the insurgencies, especially in Venezuela. Marker uses the Cuban experience as something of a guide for the rise and fall of the New Left, often in interviews and speeches given by Fidel Castro himself (just to note, this film is not some long humorless political screed, it’s often filled with wry commentary and absurdism; in particular, Marker points out Castro’s needs to continually adjust his podium microphones when he speaks, a habit he picked up when he was an inexperienced speaker, it’s almost pathological, especially when presented in an repetitive montage; the funniest part is when Castro is visiting the USSR and is forced to use a completely immovable, boxy Soviet microphone, it just looks so odd). Early in the film, Castro, when interviewed, is wearing some “casual” (if that is the right word) army fatigues, lounging in the grass, and expousing liberation ideology. As time goes on, we see how his revolutionary idealism becomes compromised, first in a wishy-washy speech concerning the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and even later, during the First Congress of the Cuban Communist Party, which has the all the bureaucratic trappings (as well as pomp and circumstance) of a traditional Soviet event, with Castro even wearing an elaborate dress uniform. It’s almost impossible not to compare the Cuban CP Congress with the Czech’s 14th Party Congress, which was held in response to the Soviet invasion, and was probably the closest realization to a true socialist democracy (before it was nullified by the Soviet’s and their proxies).

Failure and resignation hangs over the majority of the film, even in the supposed good times. As one commentator notes, the life of a revolutionary is not easy, and it becomes even less so as times passes. The events of May 1968 sputtered to an end, because the solidarity between the unions and students splintered (according to the film, the union leadership drew concession from the government/employers, drawing workers away from the protests); in less than a month’s time, the students were tilting at windmills, deprived of targets. The end of Gaullist government control, led the French Communist Party to ally themselves with the Socialists in a Popular Unity government, betraying any sort of revolutionary ideals (one commentator notes “The slowest party to de-Stalinize was the quickest to de-Leninize), and strangling any possible collaboration between the trade unionists and the New Left (in one sequence, some protesting Trotskyites are vilified as fascists by some mainstream Communists outside a Renault factory). Splintered and weakened, deprived of active support from either of the three examples (China, Cuba, and Czechoslovakia), and with a lack of focus following May 1968 and the end of the Vietnam War, the New Left effectively falls apart, rising to the occasion for the occasional local issue (the one featured in the film, is of Japanese villagers confronting the corporation dumping mercury into the water and poisoning the villagers). By 1977, when the film was initially released, the May Day Celebration was relatively feeble. But on some level, hope and idealism lives on; one protester from Berkeley compared the 1968-69 USA with the 1905 Russian Revolution, and notes we have 12 years left to see what will happen (we got a “revolution” all right, but I don’t think he meant the Reagan Revolution).

At this point, Marker begins to conclude his film with a reedited coda, musing about the time that has passed since his film was initially released, and the end of the Soviet Union. Regretfully, Marker notes that the end of the Soviet Union also spelled the real end of the New Left; even if they were as anti-Soviet as can be, they’re ideology was also discredited. Marker ends the film on a somewhat ambiguous note, which is a modified version of his original ending (as stated in the narration). A helicopter hovers overhead, a hunter hanging out the open door, mercilessly shooting wolves as part of some population control. Even though all the wolves shown on-screen are shot dead, Marker notes that some wolves always manage to escape.

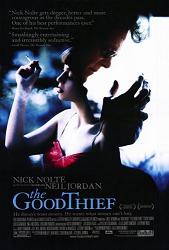

The Good Thief

In Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1955 film

Bob le Flambeur the title character, an addicted gambler and aging thief, keeps a slot machine neatly hidden

in his closet, an extension of the masked seriousness of the film’s noir setting; the Bob of Neil Jordan’s surprisingly fresh revision of Melville’s scenario keeps a roulette wheel in the center of his living room and in

The Good Thief it is a embodiment not only of the far more visible harsh reality of Bob’s addictions but also of a change in tone from the original film.

Le Flambeur’s funky closet casino suggests all of the light, humorous noir posing of Melville’s classic, the realities of gambling kept quietly behind closed doors, just as Bob’s roulette wheel pushes his character’s dark whims from a devil-may-care atmosphere to the more authentically noir street callousness of Jordon’s world: Bob’s a drinker, a gambler, an old man, a heroin addict and dead broke.

Played to perfection by a disturbingly honest Nick Nolte, the Bob of

The Good Thief looks the way Tom Waits sounds and in his worst moments even sounds the way Waits sounds, with the second half of each sentence trailing off into a growling, raspy oblivion. To keep

The Good Thief just as satisfying as its predecessor Jordan wisely sets Nolte’s visible grittiness of in a lustrous and shadowed Monte Carlo all full of smoke and neon-if someone gave Christopher Doyle Monte Carlo instead of Hong Kong, Nick Nolte instead of Tony Leung and a steadicam instead of a handheld, you would end up with the dark and dirty gloss of Bob’s sleepless nights.

The

plot is classic heist noir, and deliciously generic. As an old thief, convention necessitates Bob to attempt one last score to go out with a bang, and he finds room during his busy days of kicking the habit, shielding a gorgeous young woman from the streets, and dodging the cops and snitches to come up with a heist scam with the elegance and sense of fun embodied in the whole film. Like the some of the best of Raymond Chandler’s work, the plot of the hard-boiler isn’t quite as important as the characters who lurk the streets and spit wit hidden behind urban slang, and while the film never achieves noir perfection (a feat I doubt

The Good Thief was even aiming at, it is quite aware this is all just for fun), Jordan liberally peppers the film with enough stinging one-liners and enough interesting characters played by an international cast to let one forget they are watching slick fluff.

The most prominent among Bob’s crowd is Police Lt. Roger, who amusingly wants to stop the heist before it starts because it would break his heart to jail his old friend Bob; Roger owes Bob a life debt and the inimitable Tchéky Karyo brings to the generic French inspector role a suppressed humor and talent for verbal banter that makes his relationship with Nolte almost tender.

Suddenly reappearing in an English film after his spectacular turn as the Iraqi interrogator in

Three Kings, Saïd Taghmaoui pops up in

The Good Thief in one of the best roles from the original film: the young wannabe gangster who idolizes Bob to such an extent that he gladly picks up Bob’s sexual leftovers. The small little creature in question in this tale is the slinkiest, sexiest, most surprising member of Bob’s crew, Anne (played by Nutsa Kukhianidze in her film debut). Sleepy voiced and halfway to a life on the streets Bob nobly rescues her from a pimp and forever gains the smoky allure of one of the best femmes within recent memory to be shot with a canted angle and chiaroscuro lighting. Like Soderbergh in the

Ocean’s 11 remake, Neil Jordan has the sense to keep violence and unnecessary sex as far away as possible in his film, though both are bound to pop up eventually, albeit gracefully. In a cinema replete with numerous mediocre and exploitive crime thrillers, an exotic local populated by a talent cache of unique foreign faces and spearheaded by the familiar, expert slumming of Nick Nolte,

The Good Thief freshly updates a fun classic by tainting it with a lovingly stylized dark tone, making it the best piece of pseudo-noir fluff in a long time.