Johnny Eager

Johnny Eager, 1941, MGM (starring Robert Taylor, Lana Turner, Van Heflin and Edward Arnold; directed by Mervyn LeRoy)

MGM wasn't known for crime dramas or gangster pictures; that was Warner Bros. territory. MGM was famous for its big budget epics and its sophisticated leading men and women. Johnny Eager doesn't look like other gangster movies of its time as a result -- it doesn't have the gritty realism of The Public Enemy and Angels with Dirty Faces or the seediness of Little Caesar. MGM provides the genre with a bigger budget for flashier-looking sets, and glamorous leads in the form of Robert Taylor and Lana Turner.

Johnny Eager (Robert Taylor) is a racketeer looking to break the big time with his new dog track, but is getting heat from District Attorney Farrell (Edward Arnold). He is further distracted by a love affair with Lisbeth (Lana Turner), an uptown society girl who just happens to be the D.A.'s daughter, double-crossing underlings, and rival mobsters.

Like most gangster pictures, this is a story of moral redemption that comes too late. Johnny is not a nice kid who just fell in with the wrong guys, he's not a basically good guy who was tempted by the easy money of organized crime, and he's not just trying to make enough dough to get his mom that operation she needs. Johnny Eager is thug and a criminal. He's on top because he looks out for himself and himself alone. He trusts no one, and he's not above using those closest to him to get what he wants, including Lisbeth.

From the start of their relationship, Lisbeth is clearly out of Johnny's league – not just because she's a rich society girl, but because she's a nice girl, and an educated one at that. When they first meet, she quotes Cyrano De Bergerac to him (not a randomly chosen piece, that). He's intrigued by her because she's a challenge and a change of pace; she's attracted to him because he's thrilling and dangerous. She just doesn't realize how dangerous.

No sooner do she and Johnny hook up than she starts trying to reform him. She is even so charmingly naive as to postulate aloud that maybe the reason he went down the crooked path is that he never had a dog when he was a kid. She trusts Johnny implicitly; she believes him when he says he loves her, and that's what makes it so easy for him to take advantage of her.

Lisbeth is, in fact, very much like Johnny's improbable pal Jeff Hartnett (Van Heflin), the well-educated and verbose right-hand man who tries to dilute his self-loathing with a brandy bottle. The movie never makes it clear exactly how these two guys became friends, but it spends a good deal of time dissecting why they remain friends. Johnny keeps Jeff around because, as Jeff puts it, "even Johnny Eager needs one friend." Jeff clings to Johnny for the same reasons Lisbeth does -- because he's attractive and powerful, and because Jeff and Lisbeth both see something in Johnny that even he himself doesn't know exists: a loving heart. Jeff tries to act as a sort of moral compass to Johnny, but usually all he gets for his trouble is some harsh words or a belt in the mouth.

When D.A. Farrell learns that Johnny Eager is seeing his only daughter (indeed, that he snatched her unceremoniously from the arms of her upright, staid, rich and extremely dull fiancé), he calls Johnny into his office for a warning: leave Lisbeth alone, or he'll personally see to it that Johnny will be sent back up the river. Eagle-eyed movie fans will recognize this scene as the one Steve Martin used in his landmark detective spoof Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid.

Johnny, not one to accept threats lightly, plays the ace up his sleeve. He stages a fake murder, makes Lisbeth believe she's killed the man, and promises to cover it up. Then he goes to the D.A. and threatens to spill it all unless Farrell lifts the ban on his dog racing track. Farrell is appalled, but admits that Johnny's got the upper hand and relents.

Finally, things are going Johnny's way. His dog track will open on time, his double-crossing associates have been dealt with -- permanently -- and he's got the D.A. off his back. The only thing that can stop him now is his conscience, when he discovers that he has one.

Lisbeth, tortured by guilt over her "murderous" act, is on the edge of a nervous breakdown when Johnny finally comes to see her, and when he realizes what she's prepared to sacrifice because she loves him, something finally clicks inside of him. He confesses to her that the murder was a fake -- the gun was loaded with blanks, she didn't kill anyone, the man she shot is fine and walking around as if nothing happened. But she thinks he's just trying to ease her conscience, so he sets out to prove it to her.

The plot becomes muddled in the end, with more double-crossing henchmen at the last minute, leading to a pitched gun battle in the street, but not before Johnny has righted all his wrongs and sent Lisbeth back to the stable and loving arms of her dull fiancé, for her own good.

Despite the hurried feeling of the last ten minutes or so, this is a well-crafted story with some very nice plot touches along the way. There is a recurring motif with an honest cop, Badge No. 711, who is troublesome to Johnny's gambling rackets. Lisbeth's reference to Cyrano early on in the film serves as a kind of thematic backdrop -- just as Cyrano denied his love to spare Roxanne, Johnny pushes Lisbeth away because he knows he's no good for her.

Performances are all top-notch, from the leads on down to Connie Gilchrist and Robin Raymond in one brief scene as Johnny's aunt and young cousin. The only weak link might be Robert Sterling as the hapless cuckolded fiancé, but his role doesn't give him much to do but stand around and look like a martyr. Lana Turner is breathtaking to look at, and her acting ability never fails to catch me off-guard. Robert Taylor is a commanding presence as Johnny and Edward Arnold does his typical rich-white-conservative guy -- if you've seen him in any other movie, you've probably seen him play the same role. But it's Van Heflin who marches off with the acting honors (and the Academy statuette) as the tortured, philosophical lush.

Director Mervyn LeRoy draws on his experience with gritty crime dramas such as Little Caesar and I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang, and infuses it with typical MGM gloss. It's a cleaner, less dangerous-looking underworld, but what it loses in violent realism, it makes up for in an intellectual bent that Warner Bros. couldn't match. Unfortunately, not yet available on DVD.

City of God

The opening (and for the most part, closing) scene of the new Brazilian film City of God reminds me of a scene in the one Boetticher Western that I did not write a review for, the hilariously absurd Buchanan Rides Alone. Towards the end of that movie, one character is sent out onto a short bridge to retrieve some money left in some saddlebags. The catch, the bridge smack dab in the middle of two sides with guns drawn, each threatening to kill the poor shlub who was sent out to retrieve the money in the first place. That kind of damned if you, damned if you don’t attitude permeates the newer, Brazilian crime film; hell, at one point the narrator of the film, Rocket (the character being based on the photojournalist and novelist Paulo Lins, whose book the movie is based upon) aptly sums it up: “If you run away, they get you, and if you stay, they get you, too.” He’s of course referring to the criminal gangs, comprised mainly of local children and teenagers, which wage almost open warfare in the Rio de Janeiro favela of Cidade De Deus (“City of God”). Probably one of the most ironically named bureaucratic feats in recent memory, Cidade De Deus was the product of a conservative government which wanted to get the poor, and mainly black residents of the Rio De Janeiro slums out of the way, so as not to upset the tourists. Then they were pretty much forgotten, cast away with little or no material comforts or opportunity, and with even less and less space, as the government kept up it’s relocation program, jamming more and more people into the crowded favela (in the film, which spans two decades, from the 1960s through the 1970s, the Cidade De Deus transforms itself from a dusty collection of nearly identical bungalows into a grimy, concrete slum, or as Rocket puts it, from Purgatory to Hell), where they were at the mercy of gangs or the corrupt police force (apparently, the Cidade De Deus is so violent, that the movie had to be shot in other, relatively less violent, neighboring favelas in Rio).

At it’s most basic, the movie is an example of a well-trodden genre, the precipitous rise and fall of the gangster, in this case, the sociopathic cocaine kingpin known as Li’l Ze, as seen through the eyes of Rocket, a good kid trying to just survive and to get laid (his own attempts at crime are comedically inept). The film traces Li’l Ze from when he was a kid in the 1960s, known as Li’l Dice, whose older brother, along with Rocket’s, was part of a Robin Hood-esque gang of inept robbers nicknamed “The Tender Trio.” Then it’s onto the 1970s when Li’l Ze takes over the drug rackets in the Cidade, leaving only him, and a white dealer named Carrot, to vie for total control. A vicious rape leads to an ever escalating gang war, culminating in a final chilling bloodbath, as the formerly powerful Li’l Ze is gunned down by a gang of 10 and 11 year olds, beginning the cycle of violence anew (the final shots of the film are of the bunch of kids, known throughout the movie as the “Runts” walking down the street, brandishing automatic pistols, discussing who they should kill next). There’s even a certain mystical quality to the narrative; Li’l Dice is christened Li’l Ze by some sort of witch doctor who gives him a talisman and promises him power, but only if he refrains from fornicating while wearing the talisman. And, of course, it is the rape which leads to his downfall, by prompting Knockout Ned, an ex-soldier, to join forces with Carrot (which leads to a seemingly never ending cycle of revenge, death, and more revenge). The story of the film is of course, based on actual events and people, at the end of the scene, we are treated to still photos of most of the principal characters, as well as a short TV news interview with an imprisoned Knockout Ned, an interview which is actually re-created, quite faithfully I may add, in the film itself.

In many ways, the character of Li’l Ze reminds me of the protagonist of De Palma’s Scarface, certainly a cinematic touchstone for just about every crime/drug lord film of the past twenty years. But while De Palma was looking way back in the past with his remake, City of Gods director Fernando Meirelles (also, depending on which review or article you read, Katia Lund is sometimes credited as co-director, she is a documentary filmmaker who had worked previously in the favelas, and worked with other collaborators to train the many non-actors who comprise the films cast, many of whom are actually from a local theater troupe organized from the youth of the Rio favelas, Nos de morro) sets his eyes on more recent cinematic history, specifically films like Goodfellas and Pulp Fiction. Like the former film, City of God shares a constant, very detailed voice-over narration describing the in and outs of the Cidade de Deus’s history and culture with an almost anthropological eye (I dryly remarked to a coworker today that I now know how to run my own ruthless, street-level narcotics gang); the big difference is that Henry Hill was an intimate player in Goodfellas, while Rocket, other than being a witness, or better yet a survivor, is almost incidental to the events of the story, giving the whole thing an air of detachment.

Meirelles, a former commercial director, creates a kinetic and violent narrative, using just about every trick in the book both old a new, in a self-consciously flashy manner, which could quickly become tiring if it wasn’t an example of bravura filmmaking, or anchored to an interesting story (it also helps that Meirelles, who also works with a huge cast of largely non-professional child and teenage actors and a complicated narrative, knows how to slow down when appropriate to a scene, like in the many bedroom or beachside interludes)  . One of the best examples is the oft talked about opening sequence: a propulsive, expertly cut montage that plunges you right into the thick of things (quick cuts of a knife being sharpened, chickens running around, the smiling cocksure menace of Li’l Ze, heavily armed children openly parading around with guns) before enveloping Rocket into the affair (the stand-off between the police and Li’l Ze’s gang that I mentioned in my opening paragraphs) quite literally, with a digitally-enhanced 360? swoop around Rocket showing just how screwed he really is, before morphing into the one of many flashbacks (this to both Rocket and the favela’s childhood).

Other scenes that I specifically notes includes the death scene of Shaggy, the ostensible leader of the Tender Trio, fleeing the police, running full stop through the narrow alley ways of the closely-bunched bungalows, as his girlfriend (and camera) watches from a car barreling down the dusty road at an equal speed. Gunned down by the police, more interested in vengeance than justice, for a crime that was actually perpetrated by the already psychotic Li’l Dice/Li’l Ze, it’s a scene that is almost lyrical in it’s intensity, an artful, almost romantic, not quite blaze of glory, which punctuates the conclusion of both the narrative and historical era of the 1960s, a time of relative innocence.

It is also demonstrative of the range of violence that Mierelles depicts (and there’s lots of it, especially after the gang war starts, and the bodies of anonymous children, foot soldiers in the war, begin to line the streets), especially compared with the other scene that readily sticks out in my memory, when Li’l Ze enraged by the delinquency of the Runts, decides to take action, to mete out his own particular brand of justice. In a completely cold-blooded scene, Li’l Ze and his gang manage to capture two of the smallest members of the Runts, offering them a stark choice, either get shot in the hand or the foot. One, the youngest looking, sobbing like the baby he nearly is, tentatively holds out his hand, while the other huddles in the corner; Li’l Ze makes the decision for them, shooting each in the foot (all accomplished in a series of close-ups). Then Li’l Ze is overcome with “inspiration,” deciding to test the mettle of his youngest follower, an errand boy nicknamed Steak N’ Fries (basically he’s the food gopher for Li’l Ze and his top lieutenant, the more intelligent, diplomatic, and carefree Benny, probably the second most sympathetic character in the film, despite his hoodlum status, as he is the only one who can keep Li’l Ze in check, is rather good natured, loves his girlfriend, Angelica, who incidentally Rocket has a crush on, and who is played by Sonia Braga’s niece; you could see him being successful in almost anything in life, if he wasn’t born into a crime-ridden slum; his death is doubly tragic because one, he wasn’t the intended target of the assassin’s bullet, and two it allowed the maniacal Li’l Ze to be fully unleashed) by having him shoot one of the kids. Steak, almost shaking, with the gun too big for his hand, hesitates (he is shot in a low angle shot, almost from the POV of the most likely victim), but ultimately shoots the tired one in the head in an almost casual manner, mostly like too numb and too afraid to do anything else. It’s a hard scene to watch, given how Mierelles draws out the scene, and especially with Li’l Ze’s flippant commands to the surviving Runt, and it prompted the woman sitting behind me to finally walk out (also in narrative terms, this event, is the reason why the Runts finally exact vengeance on Li’l Ze at the end of the film, heavily armed, they mercilessly riddle Li’l Ze with round after round of bullets; ironically, they were armed by Li’l Ze to act as soldiers in his war with Carrot).

But what makes the film really interesting is the narrative, which is the film’s most inventive aspect (I probably should not generalize so much, but I did remark to phyrephox on AIM that it seems like Latin American filmmakers who crafted films like City of God and Amores Perros have been the only ones to really successfully take the narrative techniques popularized by Tarantino, and extrapolate and create new derivations, instead of just aping conventions such as just moving the story out of chronological order for the sake of doing so). Rocket, the ever knowledgeable narrator guides us through a narrative which is constantly looping back on itself (and often broken up by episode titles), revealing additional information, or information from a different, previously unknown perspective.

A case in point would be the multiple takes on the Hotel Miami robbery, which the Tender Trio perpetrates at the urging of Li’l Dice; we see the robbery from the Tender Trio perspective, but the narrative returns to the scene again and again, revealing more information (first we get some quick shots of the bodies, even though we hadn’t seen any of the Trio actually kill anyone, then we see what really happened, as Li’l Dice gleefully gunned down everyone he could find), adding detail and explaining events. Another example is how the film reveals the true nature of Knockout Ned’s killer. After watching the film, I thought to myself, it’s almost structured like I think, with digressions onto tangents, focus on details, starting and stopping, and relooping back onto to previous subjects. My favorite narrative technique is almost like the cinematic equivalent of a really informative footnote, as Rocket, traces the history of this or that person or place. The exemplar of this narrative trait is the episode where Rocket recounts the history of a local apartment used by several “generations” of drug dealers; in probably around a minute of screen time, you get a full, complex history of one particular apartment and the people who lived there (it also introduces one of the movie’s most pivotal characters, Carrot) using a combination of dissolves and voice-over. It’s great stuff, and I loved the attention to detail and atmosphere (again, it reminds me of Scorsese and his penchant for an almost anthropological focus on detail).

An article in the January 2003 issue of Sight & Sound drew parallels between the film’s usage of non-actors drawn from the favelas to make the movie, and the figure of Rocket, who essentially escapes the favelas through his talent for photography (or more by accident, since he’s really the only way that the Rio media can get into the Cidade Des Deus). While the reason for his escape is elucidated, Rocket’s reasons for never being drawn into the life of crime are really never made clear, even after a close association with several of the pivotal criminal figures in the favelas crimeworld, especially Benny, who became something of an older brother to Rocket (Rocket’s own brother was gunned down by Li’l Dice, a scene that the film returns to twice, each time supplying more information). It must have been a combination of fear, first of his father, and then of the gangs, and ineptitude. So while living in the fray, he’s also above it. I would say his detachment grows even more once he gets behind the telephoto lens of the camera supplied by a local newspaper (they make him an intern, instead of a reporter); the final gun battle is mostly depicted from the POV of his lens, being not quite an actor in the drama around him. He even fully captures the complicity of the police force in the crime swirling around him (as the police, the best of whom are on the take, the worst of whom are the supplies to the gun dealers who bring Rugger automatic rifles and Uzi submachine guns into the favelas), though he’s faced with the resignation that those photos could never see the light of day, despite the media frenzy that the colorful and violent gangwars had created (the poor, largely black denizens of the Cidade, being the quasi-mythical Other to the middle and upper class whites of Rio, especially after Li’l Ze takes to having his photograph taken by Rocket in dynamically composed shots with his gang and their heavy weaponry). In some respects, you could say that the runaway success of City of God in Brazil is symptomatic of this same fascination, but its nice to know that some of the larger picture is not obscured anymore (and from what I’ve read, the film has actually caused some controversy and policy review in the government).

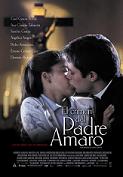

The Crime of Father Amaro

Truly controversial movies  are so rare these days in the cineplex that it becomes tiresome to watch distributors market their movies as racy simply for PR reasons (remember Eyes Wide Shut?), an especially irritating tactic when it is clear that a film like Irreversible does not even need to be marketed because it is so disturbing that word spreads about it on its own. The Crime of Padre Amaro, Mexico’s bid for the 2002 Best Foreign Film award and marketed with the tagline “one of the most controversial movies ever”, is certainly trying to bank on the false perception that the material is somehow riot inducing. Yes, it is about a Catholic Father ( Amores Perros and Y Tu Mama También heartthrob Gael García Bernal) sleeping with an underage girl (Ana Claudia Talacón)-though the age difference is never stated and both actors look roughly the same age-and yes, it is about the corruption of the Catholic Church. Maybe someone should have told the filmmakers that this is 2003, and that the source novel is over 100 years old, and that these themes (corruption in the Church, well I never!) are real old hat, and especially old hat in face of the child molesting charges the Church faced around the time The Crime of Father Amaro was released.

Not one member of the Church, from  the parishioners all the way up to the local bishop are clean in this movie, and their crimes range the gamut from the pedophilia implied with Father Amaro, to using drug money to fund a hospital, advocating abortion, pre-marital sex, gluttony, fornication, and supporting local guerillas. The film certainly paints a depressingly nonchalant picture of the state of the modern Church, but since all of the Catholics in the film appear to have no conflict between their fanatical devotion to the faith (Ms. Talacón practically has a heart attack when her boyfriend verbally slips and admits to not believing in God…) and their actions (…yet she has no problem sexually seducing Father Amaro) the movie comes off less as a criticism of the strictness or antiquated edicts of the Church than simply a large catalogue of the pitfalls that Catholics fall into in a rather rural, poorly supervised community.

The fault of The Crime of Father Amaro, with its indictment of an entire Mexican church going community, lacks is any sense of conflict. Each character leaps from emotion to emotion with no evidence of a conflicting bridge: in a blink of an eye Amaro jumps from pious, earnest devotion to suddenly deflowering a young girl under the guise of training to her to be a nun. Similarly, the Bishop speaks against Church involvement with guerrillas and then okays using drug funds, a Father denounces Amaro’s sexual relationship yet has a similar one himself, and so on with almost every actor with a speaking role. The affair between Amaro and the young girl, supposedly the highlight of the film, would appear to be youthful lust out of control if only every other character in the film, all much older than them, wasn’t just as foolishly hypocritical as they are. Nobody seems to have a problem with their double standards, not even Amaro, who for the first hour of the film gives the impression of the exact kind of sincere, devout youth that the Church would use to stave off the corruption in such small towns.

The controversial sex between the two youths is passionless as it is pointless because it is unclear what is driving these people to be as sinful as they are religious. With the exception of one particular Father who staunchly wants to preach the word of God regardless of intersession from Church elders, every single character in The Crime of Father Amaro is in the same situation of beliefs conflicting with actions, yet this conflict is only visible to the audience as none of the characters seem to be aware of the deep hypocrisy in front of them. This total vacuum of self-awareness in every single character in the film world is what prevents the movie from making any kind of intelligent comment on the current state of the Mexican Church. As the film is so sloppily spread out across characters in nearly similar situations, The Crime of Father Amaro places some kind of blame on everyone and cannot bring itself to focusing on its title character-which seems like yet another irritating marketing jab to draw attention to the film’s “controversial” indictment of the Church clergy. The entire cast is shortchanged by a script that gives everyone involved banal roles that lack the kind of dynamism that could have made the movie a study of temptation in the clergy, or upholding unrealistic laws in unusual situations, or how clergy corruption affects its parishioners or visa versa. Yes, Talacón and Bernal look good together half naked, yes, every single Catholic in the movie appears somewhat dirty, but what the The Crime of Father Amaro does is leave a slight aftertaste of anger not at the Church but at these people in the movie who do not seem to understand what the hell they are doing or why they are doing it. With a film this stale the effect of the movie’s own shortcomings on its character portrayals is just about the only thing of interest, and that is saying a lot about a movie supposedly about a scandalous passion of youthful indiscretion.

Question of the Week

Well, I was going to write my thoughts about City of God, but I got lazy and started too late, so that will have to come later. So for now I've decided to post a new question of the week; remember, the question is open to all blog members and all of our readers. Try to keep your initial response to one comments entry, or about 2500 words. This week's question has been inspired by the rash of negative reviews that have been posted on the blog in recent days: The Hours, Bend it Like Beckham, The Hunted, and The Life of David Gale have come in for some bad raps lately, and we've also seen some mixed reviews of Gerry (though this was still positive) and Irreversible. The question I'm about to propose was prompted by some of the comments surrounding Bend It Like Beckham (and forgive me for using the crude categories of "art film" and "popular cinema"), but my question is:

What is worse? An art film which fails, or a popular film which fails? Why?

|