ABC Africa

Abbas Kiarostami is one of my favorite filmmakers, so I would never dream of missing one of his films being screened here in Madison (now only if the Cinematheque would put together a program of his short films and documentaries prior to 1987’s

Where is the the Friends Home?), so I was excited by the prospect of a screening of his 2001 documentary

ABC Africa, a film which met with a surprisingly mixed reaction after it’s premiere at Cannes and subsequent US theatrical release last year. Though easily Kiarostami’s most accessible film since

Where is the Friend’s Home? (especially since a majority of spoken words in the film are English), the film met with criticism because some viewers found that Kiarostami did not depict the true nature of his subject matter, the 1.6 to 2 million Ugandan children orphaned first by civil war and then by the AIDS epidemic, with the grave seriousness it deserves (I guess they want the Kiarostami to become an Iranian version of Sally Struthers), while other viewers thought the film was not “Kiarostami-esque” for them. Balderdash is what I say, but I will return to those points later.

But first I would like to address the issue of Kiarostami’s switch from 35mm film to digital video; after making

ABC Africa, Kiarostami publicly declared, for both aesthetic and logistical reasons (he thinks of the DV camera as both more intimate and more immediate), that he would not return to using film, a trend which has continued at least to his latest film,

Ten (which I will be seeing two weeks from tomorrow). For better and for worse (to get the worse part quickly out of the way, the switch to digital video, in it’s current technical incarnation, pretty much rules out the breathtaking landscapes of

The Wind Will Carry Us), I’m excited by the prospect.

ABC Africa, along with another, contemporaneous DV documentary made by a world-class auteur, Agnes Varda’s

The Gleaners and I, points the way to an original digital cinema aesthetic (I’m excited by the prospect of digital cinema in general because it opens up access, again for better and for worse, to filmmaking), an aesthetic of near complete freedom, spontaneity, impromptu moments, of a roving camera eye (these qualities would be especially interesting in the tradition of the filmed diary, essay, and travelogue, which both

ABC Africa and

The Gleaners and I represent). One of my favorite moments in

ABC Africa is when one of the camera crew (I’m pretty sure that most of the film was shot with two DV camera, at least these are the two seen in the film, one handled by Kiarostami, the other by the credited cinematographer, Seyfolah Samadian) is simply wandering around a local bazaar, and as he walks down the street, the camera passes an alleyway between two buildings, in which a young child rests against the wall. You could tell that the cameraman’s interest was piqued when he suddenly paused, and then backed-up to get another shot of the child. It’s not a particularly important or revelatory shot (though I found it funny, because I expected the cameraman, after passing the alley, to back up and investigate further) but it does represent the freedom that using digital cameras entail.

Now onto the rest of the film. Kiarostami was invited to the Ugandan village of Masaka at the behest of the UN International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) to create a documentary about the Uganda Women’s Effort to Save Orphans (UWESO)

. The film actually begins with a close-up shot of the fax from IFAD rising from the fax machine, as a female narrator, in English, dryly intones the contents of the fax. IFAD wants to bring attention to the UWESO program (which essentially is a village by village cooperative of women who take in orphans and invest in an economic program of both individual and collective savings), and would Kiarostami come to Uganda to make the documentary. This he did, for ten days in 2000; he intended to use the digital video cameras and still photography as visual notes for the upcoming documentary, but when the small film crew returned to Iran and viewed the tapes, they saw that they already had enough raw materials for the documentary proper. Much of the criticism directed at the film comes from the fact that a large percentage of the film is of smiling children, laughing, mugging, singing, and playing for the camera, prompting some to ask, “Where is the misery?”

Well, it’s all around them, Kiarostami’s tour of Masaka includes plenty of scenes of poverty and death. It’s actually almost always present, much like the many condom billboards that dot the city and countryside (if anything, an ever present reminder of the presence of HIV and AIDS; it also introduces some subtle criticism of the Catholic Church and it’s response to the African AIDS crisis, given the church’s hostility to birth control and family planning). In the film’s most harrowing scene, Kiarostami and his crew visit a compound that houses both children and adults afflicted with AIDS. As the Kiarostami and company drive to the compound, they first pass a busy coffin making enterprise, with coffins of various sizes stacked around outside; even after passing the busy carpenters, the pounding of hammers and nails continues on the soundtrack for the first few minutes of the visit to the medical compound (a group of decaying buildings surrounded by a barb wire fence), before replacing them with the incessant wail of children in pain (even in the adult wards). It’s not a pleasant picture, and the sequence is capped-off with Kiarostami and crew capturing what happens to the dead. A young child’s body is unceremoniously wrapped in sheets and cardboard, before being tethered to a bicycle, presumably to be buried. Two things are striking about this sequence: one, it was immediately preceded by some jovial conversations between Charles, an UWESO worker who is acting as tour guide and translator to Kiarostami and his crew (he, along with another female worker, provide the majority of the context in voice-over, citing the recent history of Uganda, the statistics surrounding the orphans and the AIDS epidemic, and explaining how the UWESO program works), and a nurse at the compound (as always, like the children and women dancing and singing, Kiarostami seems to be saying, life goes on), and two, Kiarostami periodically enters the shot.

As much as it is a documentary about orphans and local problems,

ABC Africa is as much a documentary about it’s own making. Throughout the film, various crew members enter the shot as they are filming or snapping still pictures (we actually see a lot of the two cameras being used, especially since they elicit such curiosity from the assembled children) or just playing around (in one of the first car rides, Kiarostami and Samadian turn their cameras on each other); at other times you hear Kiarostami ask questions or request that someone do something. In one key scene (which is after one of my favorite scenes of the movie, which I will get to later), Samadian is filming Kiarostami from his hotel room balcony, during a morning rainstorm. Kiarostami is yelling for Samadian and the others to get down on the street because he “found something worth shooting.” It turns out to be a preparation for a wedding, a scene which incidentally points out the social disparity between the relatively posh hotel that Kiarostami is staying at (all gleaming white, though even that one is not as posh as the first Ugandan hotel we see in the film; even though Iran is a Third World country, Kiarostami and company, as middle-class Tehran intellectuals, are more akin to Europeans and Americans) and many of the people of Uganda, as the six people, all teachers, and their families crowd into a house seriously damaged by the civil war, with no windows, and fading green walls. This doesn’t dissuade the happiness of the bride, who is preparing her hair, nor a toddler who plays by himself in the empty room.

Another scene which is particularly socially relevant (especially when the scene is juxtaposed with sequence immediately following it) occurs later at the hotel. While in the dining room, they film a young baby girl as she walks and crawls across the carpeted floor. She is the recently adopted daughter of an Austrian couple. They are a nice, affluent couple, who want to do right by their daughter, to the point of also exploring the local neighborhoods and bazaars, taking pictures and experiencing what they can so they can later tell their daughter what it was like (they’re not foolhardy or chauvinistic enough to actually think that they can experience the Ugandan culture, they admit that the best they can do is offer an impression, something much like

ABC Africa itself). Despite the Austrian’s promise of a loving, and materially secure home in Europe (something that the local judge also declared when he signed off on the adoption), the way Kiarostami structured the film, makes me wonder what his true feelings towards the manner are. Immediately after the sequence with the Austrian couple, Kiarostami cuts to a mass meeting of UWESO members (each village group of five women is also organized into a larger unit representing many groups). There’s a real sense of purpose and community in these scenes, of everyone sharing together for at least the prospect of a better Uganda, something that is lacking in the scenes with the Austrian couple. But like most of the film, Kiarostami does not really make overt judgments.

So what is the point of this film, with it’s walking video tour of Masaka, the hardship and misery going hand in hand with the every day living, the singing, and dancing? Well, in the most Kiarostami-esque scene in the film, Kiarostami states that “Our only good fortune is that we humans can adapt to anything.” It’s the same kind of Humanistic message that Kiarostami has displayed in such films as the

The Koker Trilogy (especially

As Life Goes On..., which is an almost perfect English-language title for

ABC Africa, and

Through the Olive Trees),

Taste of Cherry, and

The Wind Will Carry Us. It may be a truism to say so, but life does go on; what makes the truism of Kiarostami’s philosophy palatable is his attention to detail, and his filmmaking prowess.

Kiarostami utters his film’s key words during what I have called the most Kiarostami-esque sequence of the film. It’s late at night, almost midnight, and Kiarostami and his crew have assembled in the one of their hotel rooms. It’s almost completely dark, and you can not even see any of the people in the room, you can only hear their voices as they speak in Farsi. In fact, the only source of illumination is a bright light from a lamp post outside, which has attracted the attention of both the mosquitoes and the filmmakers, who marvel at the size of the bugs, and talk about Malaria (thanking that they took their pills). There is some more banter (one of the crew is sick from something he ate), while other discuss the ramifications of AIDS versus Malaria. Then someone says that the power will be turned off at midnight. The voices continue to talk comparing the conditions of Masaka to their hotel, and to Tehran, voicing the opinion that they probably couldn’t live like this (which eventually prompts Kiarostami to utter his above line). Then the power goes out, and everything is cast into total darkness. The rest of the scene lasts about five minutes, in total darkness, with the exception of a few seconds when Kiarostami lights a match in the hallway; the crew somewhat comically tries to stumble their way in the complete darkness to their room, continuing the debate as to whether they could actually adapt to these conditions. The scene actually ends with Kiarostami leaving as Samidian finds his room; a thunderstorm is already brewing out side, and Samidian trains his DV camera outside through the window. Occasionally, bright flashes of lightning illuminate the sky, before complete darkness returns and the rumbles of thunder dominate the soundtrack (again, somewhat reminiscent of the ending of

Taste of Cherry). It’s a beautiful ending to the scene, my favorite in the movie, and then there is a nice transition to the next morning; their is a fade in next morning from the same angle as the night before. Samidian hears Kiarostami from outside, leading into the wedding scene I described above.

I think I’ve already demonstrated the similarities, both aesthetically and philosophically between

ABC Africa and the rest of Kiarostami’s oeuvre: with the interest in children (this interest probably is the cause for what I think is the film’s biggest creative gaffe, superimposed still pictures of children’s faces over the clouds as Kiarostami and crew fly away from Uganda, beautiful and ghostly yes, but also a bit too sentimental); the humanist philosophy; the reflexive entry of Kiarostami and crew, which echoes

Close-Up and

Taste of Cherry, where he really does appear, and his fictional surrogates in

As Life Goes On...,

Through the Olive Trees, and

The Wind Will Carry Us; and the usage and manipulation of the soundtrack being the most important. To be thorough I think I should talk about some more moments. Of course, their are shots of people driving, as well as what is being driven past (even with the limitations of DV, they do manage to capture some very nice landscape shots), something you see in just about every Kiarostami film, and there are even moments when Kiarostami, sitting in the front passenger seat, quizzes the driver, much like moments in fictional films.

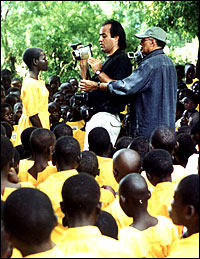

Another interesting thing that Kiarostami often does is blur the lines between documentary and fiction film (something that I think almost every great, post-WWII filmmaker has done, and must do).

Here again, we get a sense of some of the people being filmed, not only altering their behavior (we see some people shy away as the camera becomes too intrusive; it may be nice to discuss the ethical ramifications of documentary work in comments), but actively “acting” for the camera (though even this acting, is part of reality, much like the film crew). We see children hopping and skipping, singing and dancing, and at one point Kiarostami, standing amidst them encourages them to raise their arms and clap (i.e. directing them). In one telling scene early in the film, they come across a man in Masaka who kind of stares at the men with cameras, before helpfully modeling for them, almost trying to look properly destitute. This kind of blurring also extends to the narrative shape of the documentary, which is very symmetrical. After the close-up of the fax, the film begins with Kiarostami and company exiting a plane, and driving to Masaka to meet their first UWESO group; the film ends with them visiting the UWESO gathering, then driving away to the airport, where they board a plane (along with the Austrian couple and their new baby) and takeoff.

Ultimately, eventhough the film is much like his earlier work, is

ABC Africa the equal of Kiarostami’s earlier work? To be fair, I would have to say no, it’s not as poetic as his previous films (it's almost an experiment, so this should be expected), but it was fascinating in it’s own right. Now that my appetite has been whet, I’m really looking forward to the minimalism of

Ten.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home